Global Grains

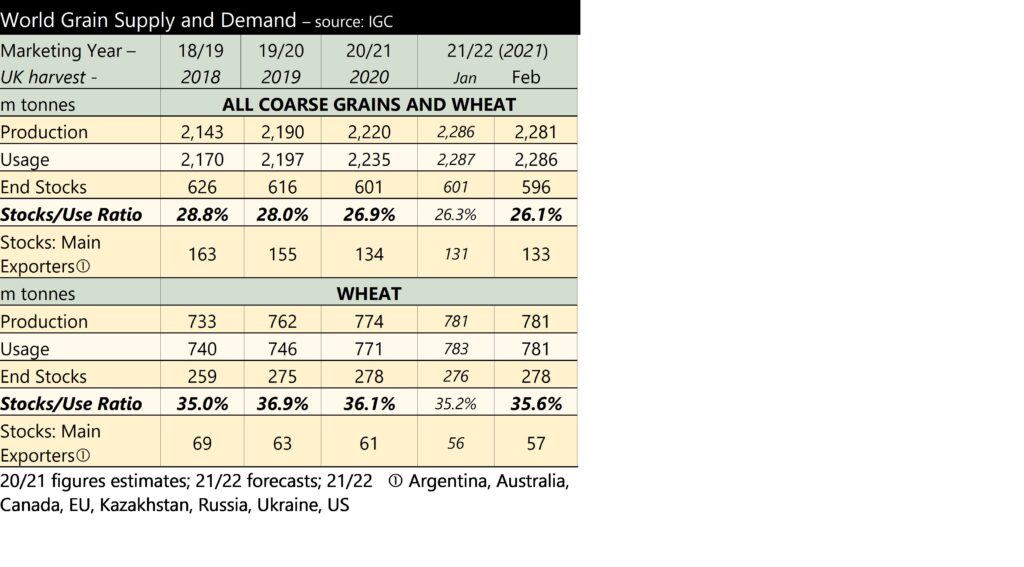

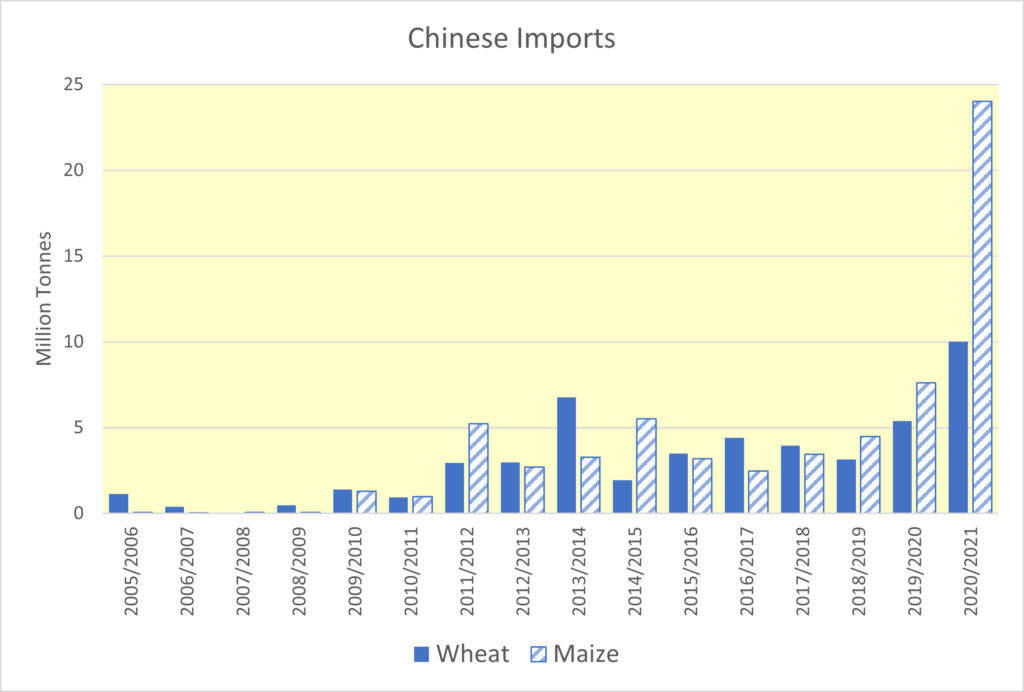

Global grain markets are largely unchanged on the month. There has been some short-term support, but there is a distinct lack of news to sustain any price increases. Both the USDA and the International Grains Council (IGC) published their latest world grain and oilseed supply and demand estimate updates. For grains, both organisations made downward revisions to global ending stocks, the USDA by 2Mt and the IGC by 6Mt. In both cases the downward revisions come from reductions to maize stocks. That said, the month-on-month reductions to the outlook are a drop in the ocean relative to the forecast 60 million tonnes of stocks.

With the US maize harvest 59% complete, the next important drivers for grain and oilseed markets are likely to come from the southern hemisphere. The picture in Brazil is split, where excess rainfall in the south is delaying soyabean plantings, whilst more rainfall is needed in the north of the country. If this continues it has the potential to support soyabean and so rapeseed prices. Beyond this, attention will turn to South American maize planting.

UK Market Update

It’s been a challenging drilling window for many so far this year. Whilst the autumn has been mild, the stop-start rains which prolonged harvest have continued. Reports suggest that pest pressures are increased, particularly for oilseed rape with both flea-beetle and slugs a problem. The relatively mild weather has seen widespread flea-beetle damage in rape crops further north than usual. In addition, storm Babet left many fields, particularly in the Midlands, East Anglia and Scotland under water.

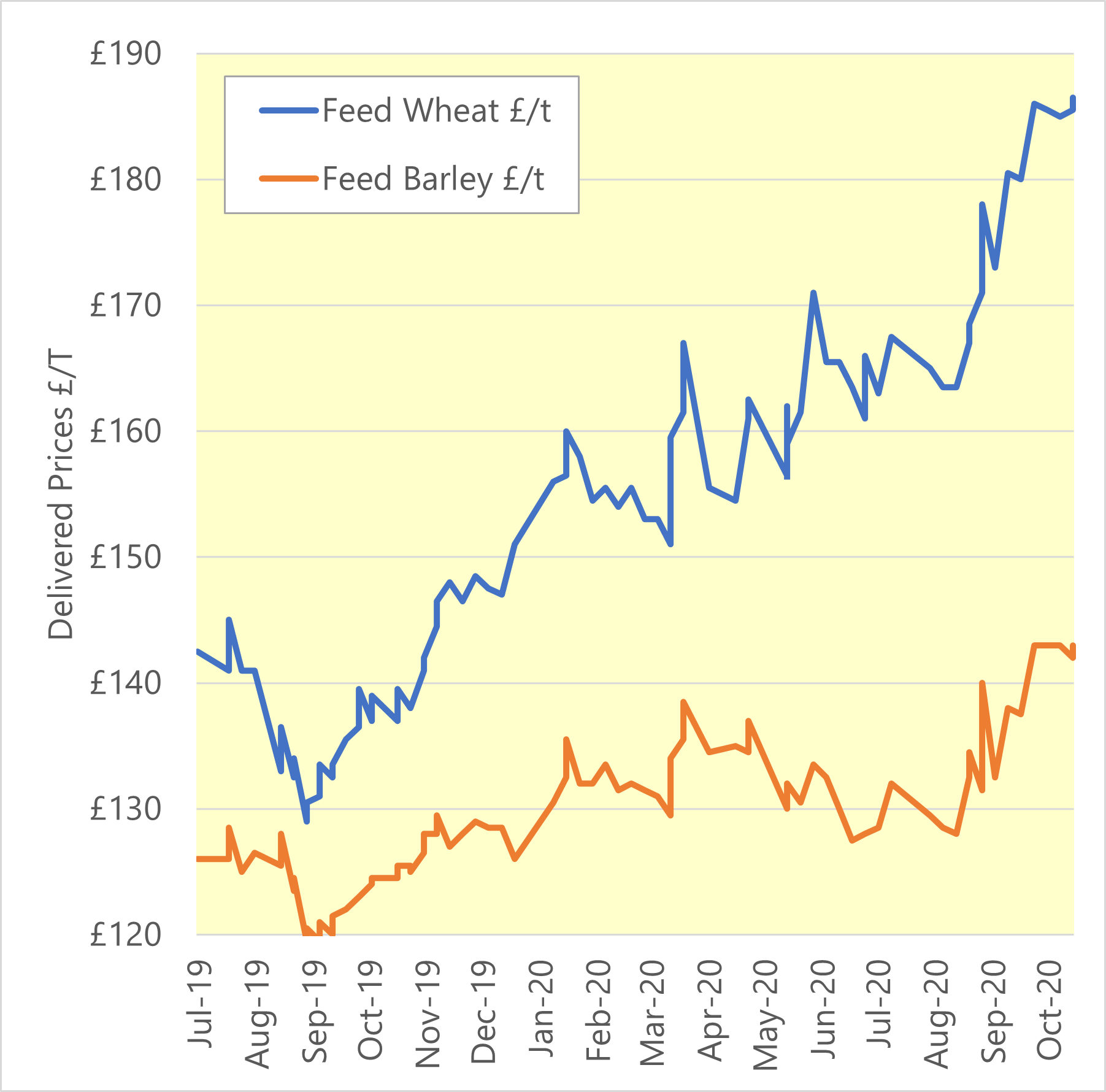

As with the global market, UK wheat prices are relatively unchanged month-on-month. There are odd opportunities to benefit from short-term spikes.

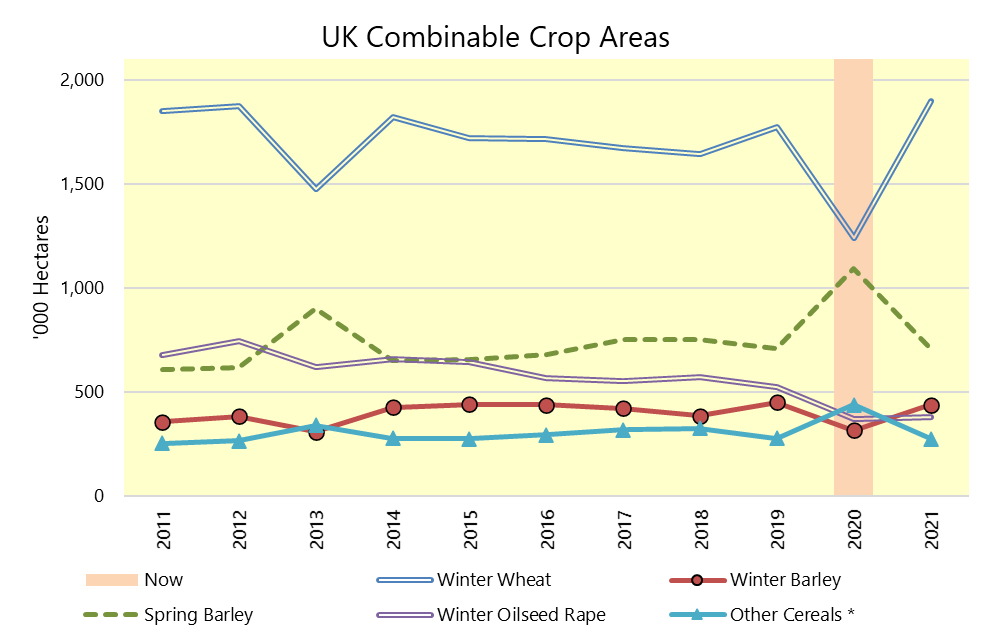

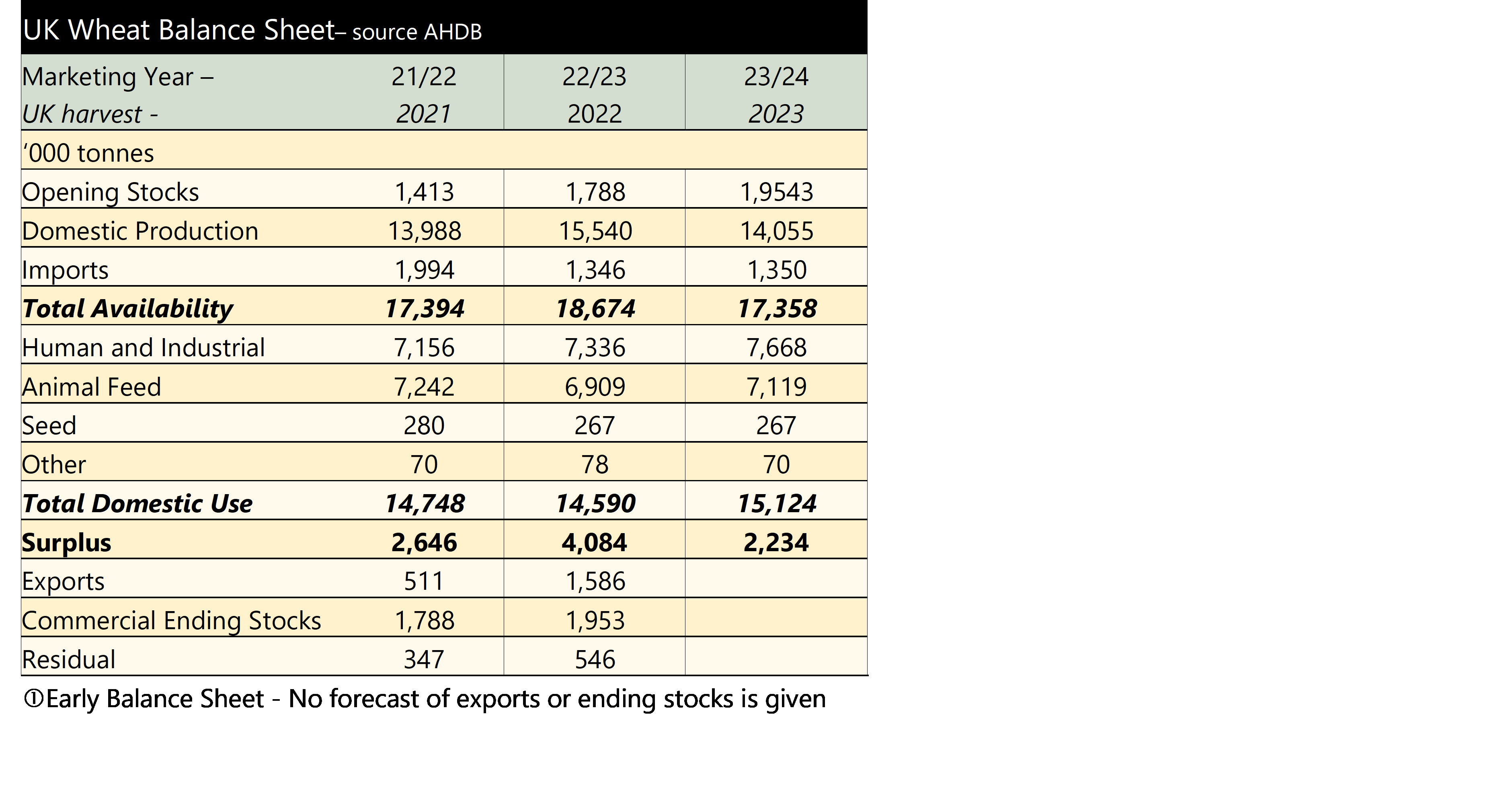

The AHDB published its ‘Early’ Balance Sheet for the UK wheat and barley market. For wheat, whilst the carry out stocks from last season are up significantly (9% year-on-year), AHDB estimates the 2023 wheat crop to be significantly smaller (14.1Mt). This is due to a much smaller planted area than had been expected. Consumption of wheat is also seen increasing, with both ethanol plants expected to remain operational. There is also expected to be a switch from barley to wheat for some animal feed compounders. With a smaller pig herd and poultry flock and reports of reasonable forage production for ruminants, there will be questions over the level of animal feed demand this season.

The UK wheat market is left in a broadly similar position as it was in the 2021/22 season. However, the lack of support in global markets and little domestic activity is keeping prices subdued. Defra will provide another update on the size of the UK wheat crop in December.

For barley, large opening stocks and decline in animal feed demand are expected to outweigh the drop in production year-on-year. As a result the UK is expected to have 1.5 million tonnes of barley which will either be held as stock or exported. Small volumes are moving, but there are currently cheaper origins than the UK for barley.

Whilst feed markets may be under pressure, there continues to be strong premiums for milling wheat and malting barley. Milling wheat premiums are in the region of £65 per tonne and malting barley premiums have reached as much as £85 per tonne. The importance of knowing and maintaining the quality in the barn cannot be overstated this season.

Pulse prices have remained firm against other combinable crops, although there are suggestions that feed beans and peas may be displaced by cheaper protein sources into animal feed. The trade expectation is that prices will fall.