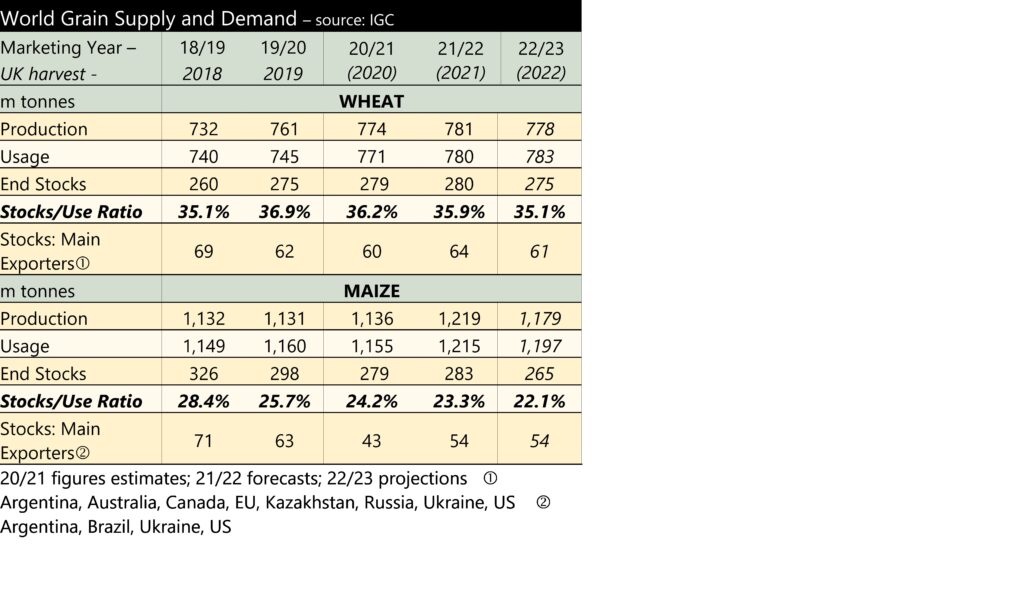

The latest International Grains Council (IGC) supply and demand figures show a year-on-year reduction of stocks of grains globally. The change in global grain supply is driven by tighter maize production, the price of which underpins the feed grains market.

The IGC forecast of maize production is ten million tonnes lower than it was in July at 1,179 million tonnes. If realised, maize production would be 40.9 million tonnes lower than in 2021/22. Even with a fall in usage, ending stocks would be 5% lower year-on-year. The maize production forecast has mostly declined due to the conflict in Ukraine. However, the impact of drought conditions in the EU cannot be overstated. Maize production in the EU is forecast at 59.6 million tonnes in 2022/23, down 8.7 million tonnes from the IGC’s July forecast.

Wheat production is forecast to decline by 2.9 million tonnes, whilst usage is seen rising by 2.5 million tonnes. Global wheat stocks are forecast to decline by 4.6 million tonnes. Excluding Chinese supply and demand from the equation, global stocks are estimated to fall by almost nine million tonnes.

With the grains supply and demand balance tightening, year-on-year, we can expect support for grain prices to remain. But, bear in mind that the lack of supply from Ukraine will already be priced-in to some degree. Any positive changes in the conflict will still drive a fall in prices.

The oilseed market is moving in the opposite direction to grains. World soyabean production is expected to increase by almost twelve million tonnes. Ending stocks of soyabeans are forecast to rise by almost ten million tonnes. The next forecasts of global supply and demand from the USDA are due on 12th September 2022, with the next IGC figures published on 22nd September 2022.