Over the last month, the prices of UK wheat and barley have fallen. This has been driven by an improved global supply and demand picture for wheat and a stronger Sterling.

Global Market Drivers

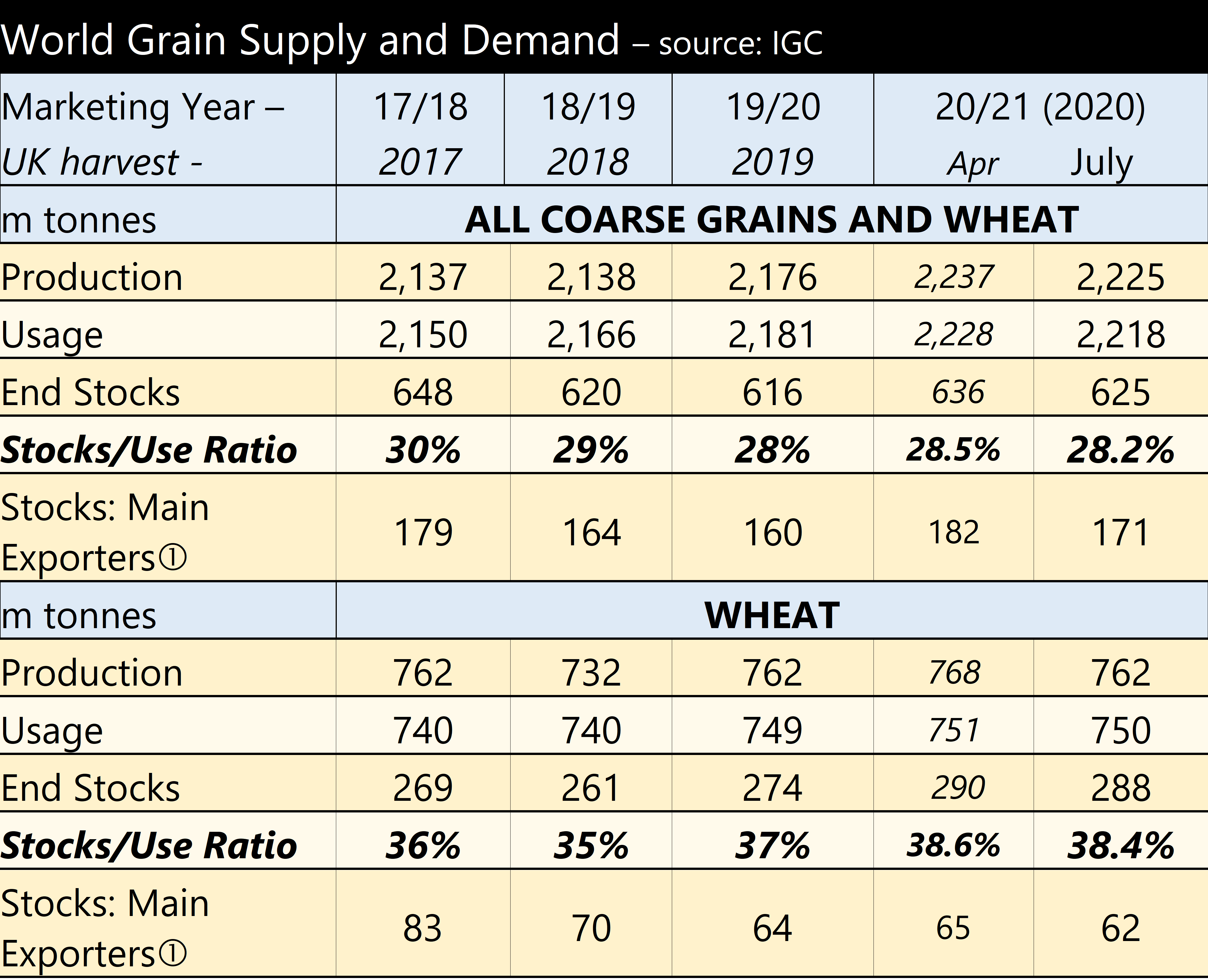

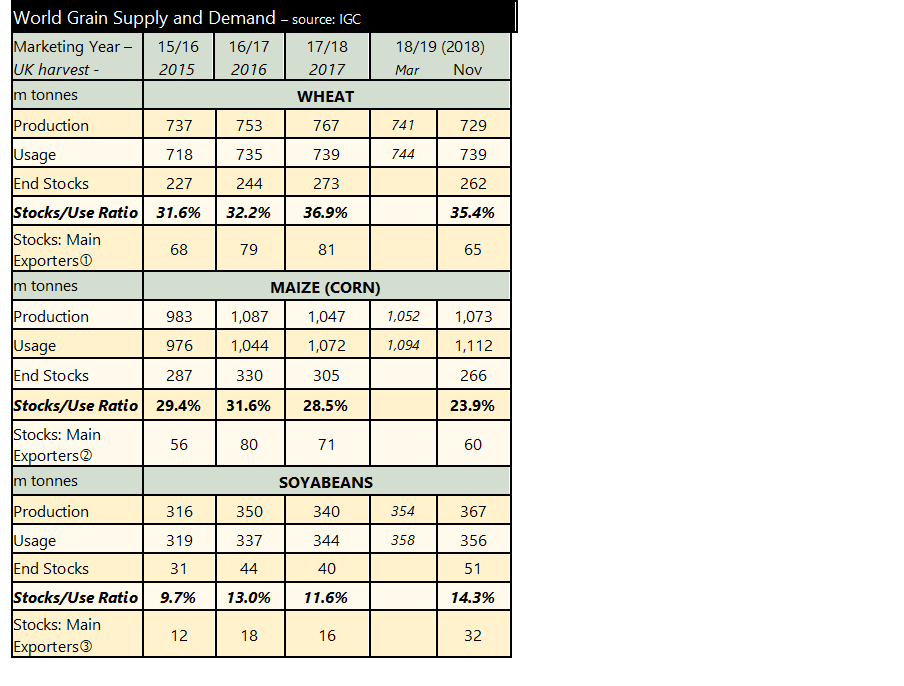

The USDA published its latest supply and demand figures early in January. The report showed improved global stocks of wheat, including amongst the top exporters. The picture for maize tightened globally, with forecasts of Brazilian production falling by three million tonnes, to 115 million tonnes. However, the combined production of maize in Brazil and Argentina was only 0.76 million tonnes below trade estimates.

South American production of maize is still something to watch closely for price direction. Rainfall has improved crop prospects lately, but Brazil and Argentina are forecast to experience drier conditions over the next few months which could hamper production, tightening global markets.

In the short-term global politics also need watching closely. Tensions between Russia and Ukraine, and in Kazakhstan, have increased global wheat futures in January. The three countries account for about a third of global wheat exports. Any escalation or de-escalation of tension will impact prices.

As we move forward, grain prices are increasingly going to be driven by the prospects for next season. The International Grains Council is forecasting that global wheat production will increase in 2022/23. Stocks are forecast to stay relatively unchanged.

Domestic Markets

UK spot ex-farm feed wheat prices fell from £219.10 per tonne on 17th December 2021, to £213.60 per tonne on 14th January 2022. As well as the global factors outlined above, the fall in prices was amplified by a 1.7% increase in Sterling against the Euro, over the same period. Milling wheat premiums remain historically strong but have fallen back recently.

UK ex-farm barley prices also moved lower across the month. The barley market is closely tracking wheat this season, with supply and demand in both markets tight. Feed barley was quoted at £203.40 per tonne on 14th January, down £5 per tonne from 17th December.

Oats have moved against other grains over the past month. The high price of other grains has increased the inclusion of oats in compound feed rations (to November) according to AHDB figures. As a result, oats have closed the gap slightly to other grains, but remain at a significant discount to barley.

Spot ex-farm feed bean prices have been flat through January, at £246 per tonne. However, reports suggest that Australia has sent large shipments to Egypt which led to price falls on increased competition.

Rapeseed prices surged again into the New Year. Demand for rapeseed oil in the EU remained strong despite high prices. Ex-farm rapeseed prices (spot) are now quoted at £613.20 per tonne. There is a significant discount into new crop, owing to better new crop prospects.