UK Harvest

Until the last week of August, harvest was a headache for many farmers. Many areas had four inches of rain in June, another four in July and about 2.5 in August, meaning the ground was soft. Intermittent showers meant progress was slow. However, the last few days have been all-systems go, facilitating a catch-up. The warm, dry, weather has also meant producers have been far less dependent on the drier than at the start of the harvest.

With a majority of cereals now cut, yields have been good to excellent overall. Winter barley has yielded higher than average with plenty of our clients reporting 8 to 8.5 tonnes per hectare (3.25-3.5t per acre). Wheat has also been very good. Strong loam soils that have been cared for with ample organic matter over the years and heavy land have achieved in excess of 11 tonnes per hectare (4½ t per acre) – and not just in isolated cases. Bushel weights of 80+ have been commonplace too, but Hagberg readings have not been as good following the intermittent rain-shine weather. Lighter soils and those with less organic matter have been affected by the dry weather in May and early June. However, yields are still good so plenty of light land farmers are recording above average results. Oats are still in the field and losing colour so possibly less attractive for milling.

OSR has been variable because a fair area had larvae feeding on plants in spring which led to poor podding in crops. That led to yields being moderate at best, many reporting around the 3-3.3 tonnes per Ha (1.2-1.3t per acre).

Beans have been at high risk of bleaching following the showery weather of the previous few weeks. Beans discolour and therefore lose value easily and quickly. Those that have managed to harvest beetle-free and coloured beans could expect a £25 to £30 premium over feed beans but the large amount of feed means this base price is not great.

European Harvest

Cereals harvests are completed in most part of the EU, including France and further South. They are near completion in Northern Germany and Poland, and well underway in Eire, Denmark, Scandinavia and Baltic States. Again, yields have been bumper. For soft wheat, Strategie Grains, an analyst company forecast European production at 143 Mt, a considerable 12.3% increase on last year. The wheat area is up by ¾ million hectares and yields are also above the 5-year average.

In France, the wheat crop will be high at 38 to 40 million tonnes depending on whom you ask. Only one Department has recorded lower than average yields and proteins are high. The German and Polish crops are also good. Even outside the EU, the Ukrainians have also had high yields, and have already started their export campaign in earnest, with higher sales than last year and a target of 21 million tonnes, which is 5.5 million more than last year.

The EU is likely to have cut over 60 million tonnes of barley this year, mostly winters. France will have seen a rise in springs because of oilseed rape problems.

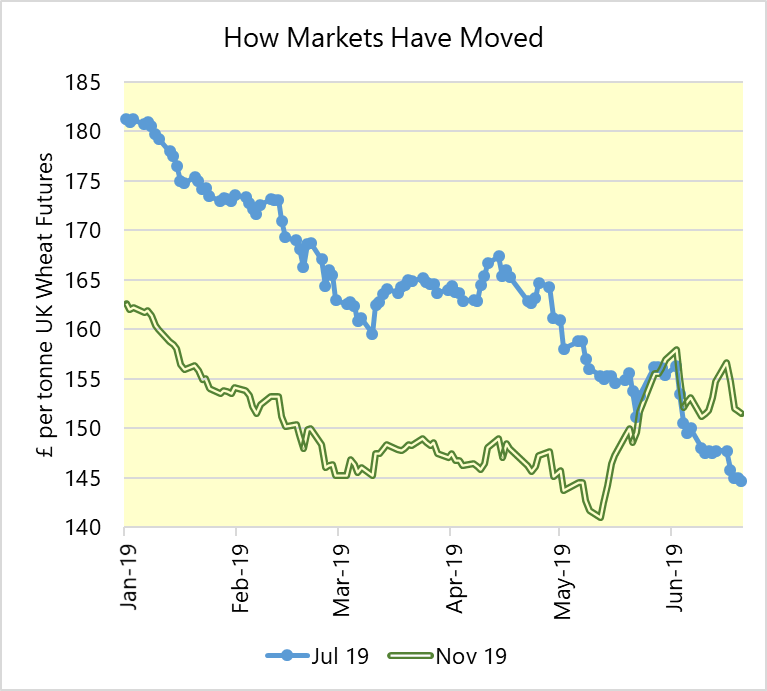

Prices

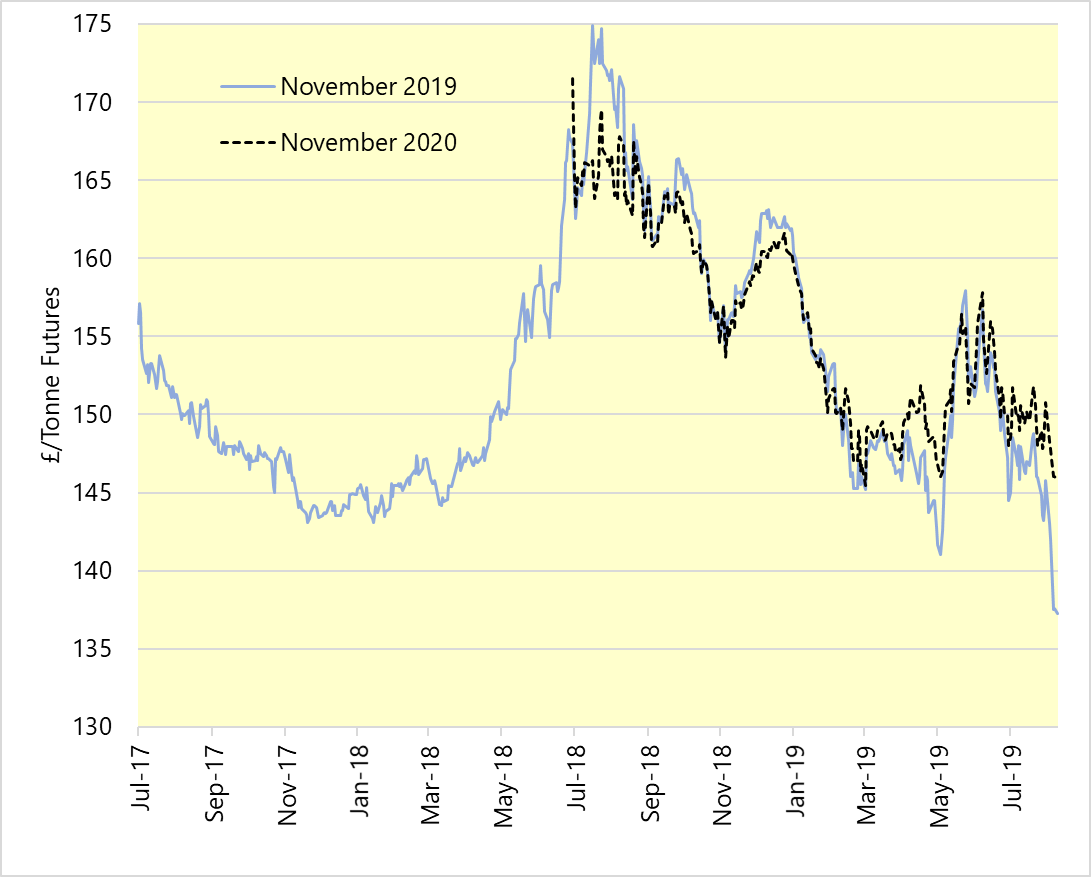

This means there will be a large EU crop this year and nearby neighbours also providing surpluses. Achieving exports from the UK might prove tricky. This explains why futures prices have hit contract lows in all positions in the last couple of weeks; we have lots to sell, everybody else who exports does too and those who import also have more grain than usual. It is clear what this might mean to prices, especially when the possibility of having tariffs looms over the UK crops. It is perhaps therefore no surprise that wheat values have fallen by £20 since June and £10 per tonne solely in August.

The weakening Pound has done little to retain any kind of value in commodities, in fact, comparing the UK Nearby wheat futures contract prices with the comparable French, a gap has opened up of about £10 per tonne more than usual. This might be the Brexit effect.