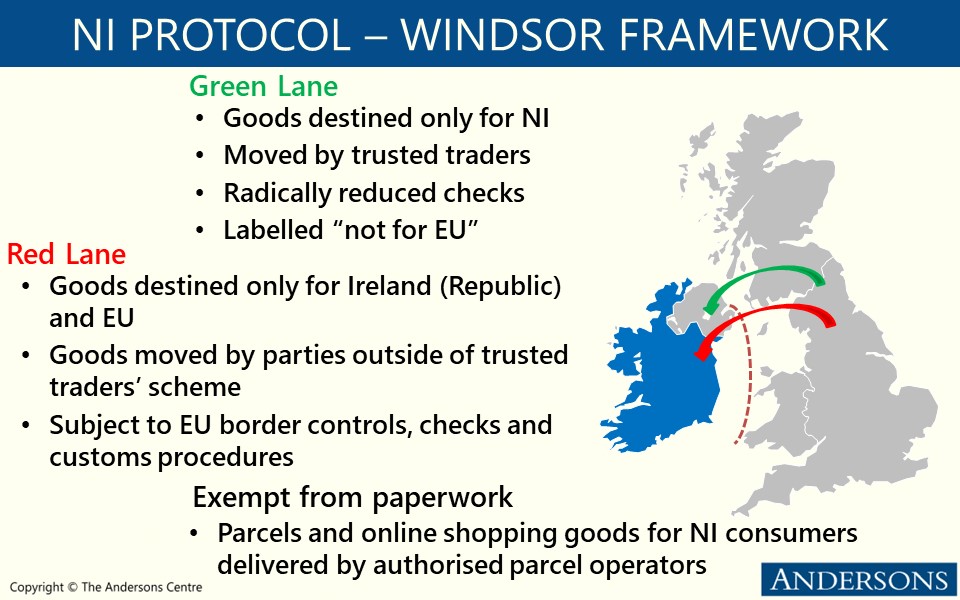

The UK Government has confirmed (yet another) delay to the implementation of its post-Brexit border controls on food and fresh products entering the UK from the EU. This time due to concerns around their impact on inflation. This is the fifth delay since 2020.

Based on the previous plan, new paperwork requirements including health certificates for certain animal and plant products, as well as for high risk foods, were going to be required from the end of October. These plans will now be delayed by a further three months meaning that the new paperwork will now not be required until the end of January 2024.

Similarly, the previous plan had envisaged physical checks at the UK border to begin in on 31 January 2024. These will now be deferred by three months until the end of April 2024. Safety and security declarations for EU imports will be delayed until October 2024.

The Cabinet Office published its latest strategy for the Target Border Operating Model (previously called the Border Operating Model) on 29th August. More detail is accessible via: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-border-controls-to-protect-the-uk-against-security-and-biosecurity-threats-and-ensure-smooth-flow-of-goods

Separately, the HMRC has also announced a ‘phased approach’ to moving exporters to its new Customs Declaration Service (CDS) which will replace the 30-year old CHIEF IT platform. The deadline for moving all export declarations to CDS had been 30th November, but exporters will now have until 30th March 2024 to move across to CDS. Notably, all import declarations have been managed by CDS since October 2022.

These delays once again illustrate the difficulties involved with replacing systems which have been in place for decades. Whilst it is important that the UK gets its border control systems right, there are concerns amongst many in the food industry that imports from the EU are essentially not getting checked. Therefore, the UK is exposed to increased risks from a food safety and food crime perspective.