With a deal on implementing the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol supposedly imminent and with the Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO) releasing its latest trade data for 2022, it is an opportune time to examine the impact of the NI Protocol on agri-food trade on the Island of Ireland.

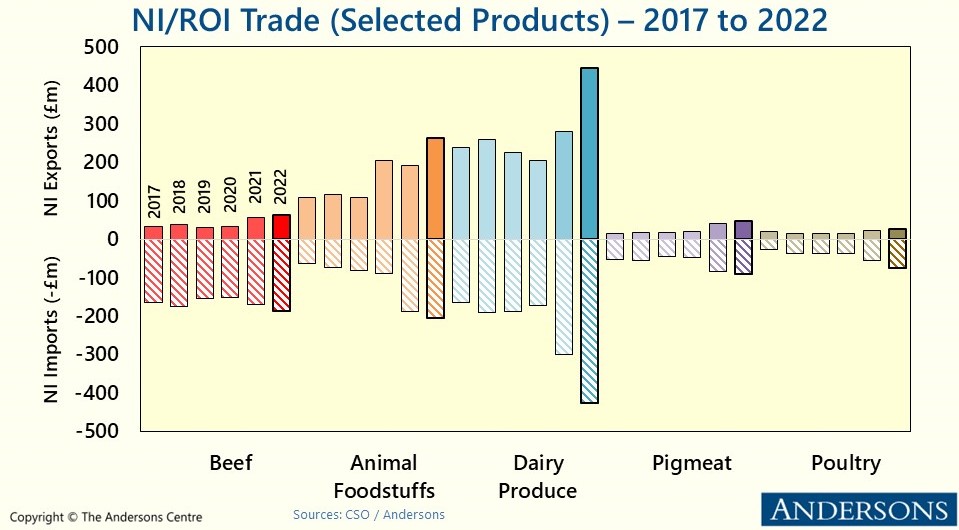

The chart below shows how agri-food trade for selected commodities has evolved in monetary (Sterling) terms between Northern Ireland and Ireland (Republic of Ireland (ROI) since 2017. It shows that since the introduction of the NI Protocol from January 2021, which has enabled Northern Ireland to stay de-facto part of the EU Single Market for goods, that trade between NI and Ireland has increased substantially for most products.

Dairy trade has seen the most significant increases, with exports of dairy produce from NI to Ireland rising by 120% since 2020 (from £202m to £446m). Imports in the opposite direction have also risen substantially from £169m to £427m. Exports of beef from NI to Ireland have doubled since 2020 and are valued at £64 million in 2022. Again, there has been a notable, though less sizeable, increase (25%) of beef imports into NI from Ireland.

Trade has also risen substantially for other commodities since 2020 with animal feedstuffs’ exports from NI to Ireland up by 125% (to £262m), whilst pigmeat exports have risen by 128% to £46m. Poultry meat exports in 2022 are estimated at £25.5m, 82% higher than in 2020.

The data presented in the chart above are in current terms. In other words, they do not take account of inflation which has been significant across agri-food during 2022. That said, given the increases reported on NI-Ireland trade, which has more than doubled in several cases, it is clear that the NI Protocol is having a significant impact on trade on the Island of Ireland.

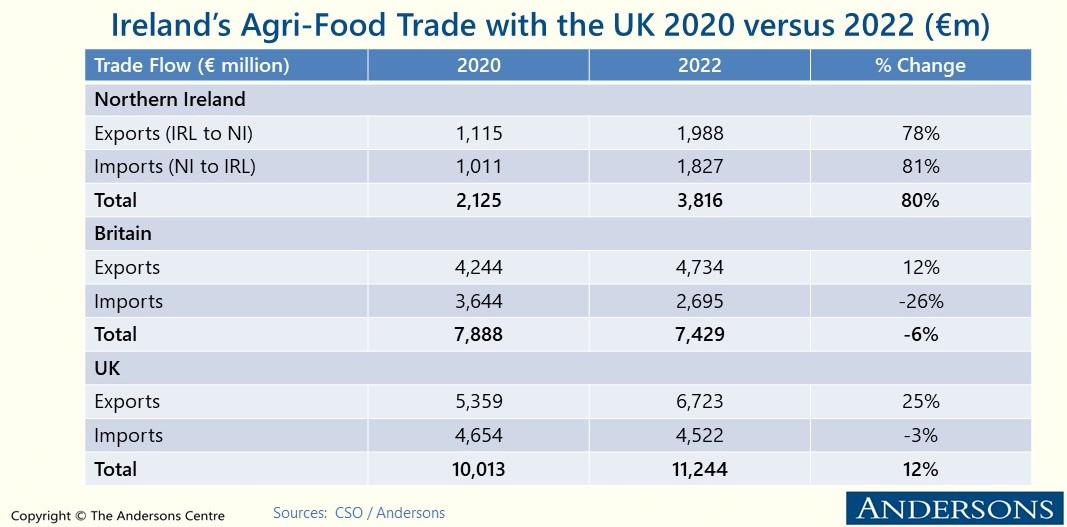

This impact becomes clearer when agri-food trade between Ireland and NI is compared with trade between Ireland and Britain. The table below shows that total agri-food trade for 2022 (imports and exports combined) between NI and Ireland is 80% higher than in 2020, whilst Ireland’s agri-food trade with Britain has fallen by 6%. This shows the clear impact of the imposition of regulatory barriers on trade between Ireland and Britain as a result of the implementation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the UK and the EU in January 2021.

Within this, it is also notable that exports from Ireland to Britain are 12% higher in 2022 versus 2020, whilst imports into Ireland from Britain are 26% lower over the same period. This shows the clear impact of the imposition of regulatory controls by EU Authorities (including in Ireland) on imports from the UK (GB) from January 2021. At the same time, the UK has continued to delay the imposition of its regulatory controls (previously called its Border Operating Model, and now termed as its Target Operating Model) until late 2023.

Overall, the CSO trade data reveals that all-island trade has increased substantially as a result of the NI Protocol and supply-chains on the island of Ireland have become much more integrated. Within this, there is also a noticeable shift in Ireland away from importing from Britain (which is now subject to regulatory controls) and sourcing more locally from Northern Ireland where there is unfettered trade.

Of course, the CSO data does not assess how NI trade with Britain (GB) has performed during this time. It is important to highlight that NI continues to have unfettered access to the GB market for its exports and the various grace periods implemented by the UK Government have, thus far, limited the imposition of regulatory checks on produce moving from GB to NI. The extent to which this trade will be affected in future is of course contingent on the detail of any agreement between the UK and the EU on implementing the NI Protocol. We will be analysing this detail as soon as it becomes available.