Tag: Brexit

UK-EU Relationship Under Labour

Following Labour’s election victory on 4th July, there has been a renewed focus on the UK-EU trading relationship and how it might evolve under the new Government. Whilst Labour has ruled out the UK rejoining the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union, below are a number of areas where, from an agri-food perspective, the UK-EU trading relationship could be improved.

- Veterinary/SPS Agreement: since 2021, UK agri-food exports to the EU have faced stringent regulatory controls and checks, while similar checks on imports into the UK from the EU are gradually being implemented. These controls, such as export health certificates and identity checks, are costly. Labour has expressed a desire to pursue a Veterinary Agreement with the EU for over a year. The impact of this agreement on reducing the regulatory burden depends on its nature. If the UK dynamically aligns with EU legislation, most checks could be removed, but the UK would have no formal vote on the rules. If the UK opts for equivalence, similar to New Zealand, checks would be reduced but still significant, and the UK would maintain control over its rules. Importantly, a Veterinary Agreement would only cover a limited aspect of the wider Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) requirements; issues such as plant health rules and phytosanitary requirements would not be included and would represent significant hurdles to trade. Therefore, Labour is increasingly talking about a wider SPS Agreement with the EU, which has merit and should be pursued. Again, there will be a trade-off between the degree of access to the EU Single Market and the control that the UK would have on the rules that apply to UK trade. The EU will also have its own perspective and will be keen to avoid the UK ‘cherry-picking’ the parts of the EU Single Market that it would like unfettered access to. An SPS deal would also benefit agri-food goods moving from GB to Northern Ireland. Whilst a deal is achievable, its comprehensiveness and the extent of regulatory burden removal remain uncertain.

- Mutual Recognition of Conformity Assessment: currently, UK products being exported to the EU (e.g. machinery) need EU-based certification to enter EU markets. This can no longer be done by UK-based laboratories, and therefore, adds costs and complexity. The UK could seek an agreement similar to those the EU has with countries like Australia and Canada, easing this burden.

- Safety & Security Declarations: post-Brexit, UK exporters must submit new export summary declarations to the EU to verify that such products do not pose risks. The UK could negotiate an agreement to remove these requirements, similar to deals the EU has with Switzerland and Norway. Again, this would require some alignment with EU rules and regulations.

- Temporary Labour and Youth Mobility: new arrangements could allow UK performers and artists to work temporarily across the EU without complex visa requirements, addressing current bilateral challenges, but importantly, it would not be Freedom of Movement. The UK could also establish reciprocal youth mobility agreements with EU countries, enabling young people to work temporarily in each other’s territories. The EU had previously made labour mobility proposals but these were rejected by the Conservative Government.

- Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications (MRPQs): the UK and EU could encourage mutual recognition of professional qualifications, easing the movement of professionals between regions. There will be difficulties here though as, within the EU, the competence for granting such recognition partly rests with Member States, so negotiations would be complex.

- Linking Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS): aligning the UK and EU’s carbon pricing systems could streamline processes and mitigate issues like the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which imposes additional requirements on UK exports of carbon-intensive goods. Whilst CBAM does not yet extend to agricultural goods, this could change in the future and from 2026, there is the potential to have charges levied on exports of certain industrial goods (e.g. fertiliser, steel and cement) to the EU.

- Joining the PEM Convention: the Pan-Euro-Mediterranean (PEM) Convention on preferential Rules of Origin (RoO) aims at establishing common RoO amongst member countries which currently include the EU, Turkey, the Ukraine and EFTA Member States. This would allow the UK to consider inputs from other PEM members as ‘local’ for meeting RoO requirements in trade agreements, potentially simplifying trade processes. However, there are difficulties as the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) rules are different to the PEM Convention in some instances and these would require aligning.

Significant improvements to the UK-EU relationship are possible, but there will still be a trade-off between access to the EU Single Market and the UK’s control over its own rules. Even with new arrangements, agri-food trade will face more friction than if the UK rejoined the EU Single Market and Customs Union, as some advocate. Sir Keir Starmer is known for seeking incremental improvements and only considering radical changes if gradual measures fail. Therefore, the Labour Government is likely to focus on the areas mentioned, leveraging the UK’s strengths in security and defence in negotiations with the EU. A deal is achievable, though its comprehensiveness and alignment with EU regulations remain uncertain.

UK Border Controls

The UK Government has confirmed (yet another) delay to the implementation of its post-Brexit border controls on food and fresh products entering the UK from the EU. This time due to concerns around their impact on inflation. This is the fifth delay since 2020.

Based on the previous plan, new paperwork requirements including health certificates for certain animal and plant products, as well as for high risk foods, were going to be required from the end of October. These plans will now be delayed by a further three months meaning that the new paperwork will now not be required until the end of January 2024.

Similarly, the previous plan had envisaged physical checks at the UK border to begin in on 31 January 2024. These will now be deferred by three months until the end of April 2024. Safety and security declarations for EU imports will be delayed until October 2024.

The Cabinet Office published its latest strategy for the Target Border Operating Model (previously called the Border Operating Model) on 29th August. More detail is accessible via: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-border-controls-to-protect-the-uk-against-security-and-biosecurity-threats-and-ensure-smooth-flow-of-goods

Separately, the HMRC has also announced a ‘phased approach’ to moving exporters to its new Customs Declaration Service (CDS) which will replace the 30-year old CHIEF IT platform. The deadline for moving all export declarations to CDS had been 30th November, but exporters will now have until 30th March 2024 to move across to CDS. Notably, all import declarations have been managed by CDS since October 2022.

These delays once again illustrate the difficulties involved with replacing systems which have been in place for decades. Whilst it is important that the UK gets its border control systems right, there are concerns amongst many in the food industry that imports from the EU are essentially not getting checked. Therefore, the UK is exposed to increased risks from a food safety and food crime perspective.

Trade Policy Blueprint

The UK Trade and Business Commission, a body consisting of business and political leaders from opposition parties as well as international trade experts, recently launched its blueprint for future trade policy. It is designed to address key barriers to trade and help grow of the UK economy. The blueprint was launched at the Trade Unlocked conference in Birmingham. This event was attended by over 650 businesses, industry leaders and several Labour MPs, including the Shadow International Trade and Foreign Secretaries. As such, the conference provided an interesting insight to the potential direction of a future Labour Government. The Commission’s recommendations, if enacted, would have significant implications for agricultural trade. They include;

- ‘Beneficial’ alignment with EU Standards and Regulations: whilst staying outside the EU Single Market and Customs Union, the Commission suggests that there is ‘everything to be gained’ by the UK aligning with EU Standards and Regulations, where it is beneficial to do so. The Commission also suggests that where it is sensible to diverge, the UK should use its freedom to do so, whilst acknowledging that costs would arise in such instances. It argues that this would give greater predictability regarding the UK’s regulatory system, helping investment. It is also seen as key to achieving a UK-EU Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and veterinary agreement – something that a future Labour Government is particularly keen on. In addition to SPS, other areas where the Commission calls for alignment include;

- Food safety: the UK should maintain and uphold the key principles of EU food safety standards, including the General Food Law (EC 178/2002) and EU regulation (EC 852/2004) on the hygiene of food stuffs.

- Chemical contaminants and residue monitoring: continue to align with EU maximum residue limits (MRLs) for pesticides and align veterinary drugs’ regulations with the EU.

- Foodborne disease surveillance and outbreak response: the UK should actively participate in the various EU surveillance networks and systems including the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) and have close collaboration with the EU across a range of other disease-related areas.

- Safeguard against lower quality imports: the UK Government should ensure that imported food products meet minimum regulatory standards that apply to domestically produced food, including on environmental requirements and animal welfare.

- Organic food equivalence: maintain regulatory alignment between the UK and EU for organic food standards to facilitate continued equivalence beyond December 2023.

- Establish a new regulatory forum for trade cooperation with the EU: this UK-EU Regulatory Council would be styled on the US-Canadian Regulatory Cooperation Council and would aim to reduce non-tariff trade barriers and build on the commitments made in the Windsor Framework. It would be established ahead of the 2026 review of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement. This is a sensible approach and the US-Canada relationship provides a useful template for how the future UK-EU trading relationship should be managed.

- Establish a new UK Board of Trade: this would be an independent body acting for the Department for Trade and Business in much the same way as the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) acts for the Treasury. As such, it would impartially assess the UK’s trading performance and help to drive improvements across Government. It would also provide impact assessments of new and existing trade deals and assess areas of divergence between the UK’s and other trading blocs’ regulations that will benefit the UK economy. Its board would include representatives from major UK business organisations, SMEs, trade unions, devolved Governments, and senior experts in trade and regulation. One would imagine that if such a body were established that it would supplant many of the functions of the Trade and Agriculture Commission.

- Visa system reform: to address labour shortages, including in agriculture. This would include a comprehensive review of the Seasonal Worker Visa Scheme to determine areas for improvement and give greater long-term certainty to businesses. It also calls for the reform of short-term and business visa rules to enable corporations to bring in highly-skilled personnel for short-term projects and to extend the maximum permissible stays under business visas to enable UK businesses to pursue longer-term projects. It also calls for a bilateral and reciprocal Youth Mobility Visa Scheme with the EU allowing young people (aged 18-35) to travel and work in both UK and the EU for up to five years. In addition, it calls for the UK to develop targeted skills development programmes to address labour shortages in specific sectors. Many in the agri-food sector are likely to be sceptical about this latter recommendation as numerous organisations have tried to recruit and train indigenous workers, with minimal success.

Overall, given the make-up of the UK Trade and Business Commission, and statements by Shadow Ministers at the UK Trade Unlocked conference, it is evident that a future Labour Government will seek a much closer relationship with the EU. Whilst the EU will be open to such an approach, it has other priorities given what is happening in Eastern Europe. Its appetite for any renegotiation of the Brexit deal is minimal. This is recognised in Labour circles; hence the focus of the UK aligning with EU regulations. The EU will also push back strongly on any attempts to dilute what it sees as the indivisibility of the Four Freedoms of the EU Single Market. Without free movement of people and leaving open the possibility for UK regulations to diverge in the future, the EU will not offer the UK frictionless trade. That said, significant improvements are possible and should be pursued.

The full report is accessible via: https://www.tradeandbusiness.uk/blueprint

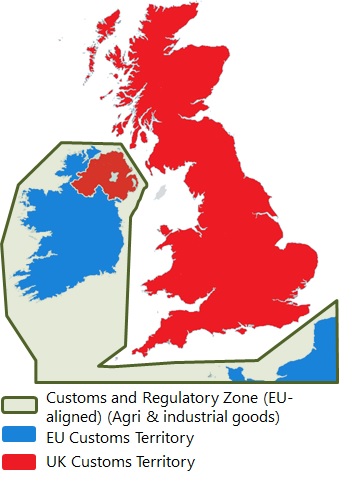

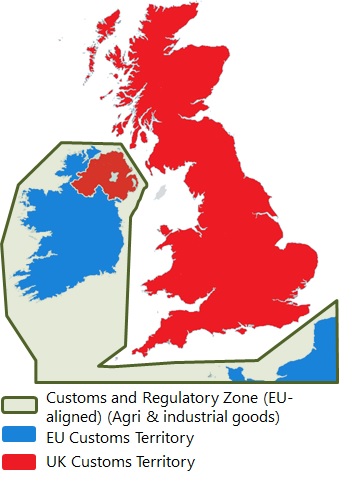

Image source: Best for Britain

Windsor Framework Agreement

On 27th February, the UK Government and EU Commission reached an agreement on the implementation of the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol – the ‘Windsor Framework’. The deal emerged after months of, often arduous, negotiations and is heralded as a major breakthrough by both the UK and EU negotiators. It is hoped that this framework will resolve the thorniest issue of the entire Brexit process and has been welcomed by most Northern Irish stakeholders, although the DUP have yet to give an official view on the Framework, which is not expected until April.

The key aspects of the agreement are:

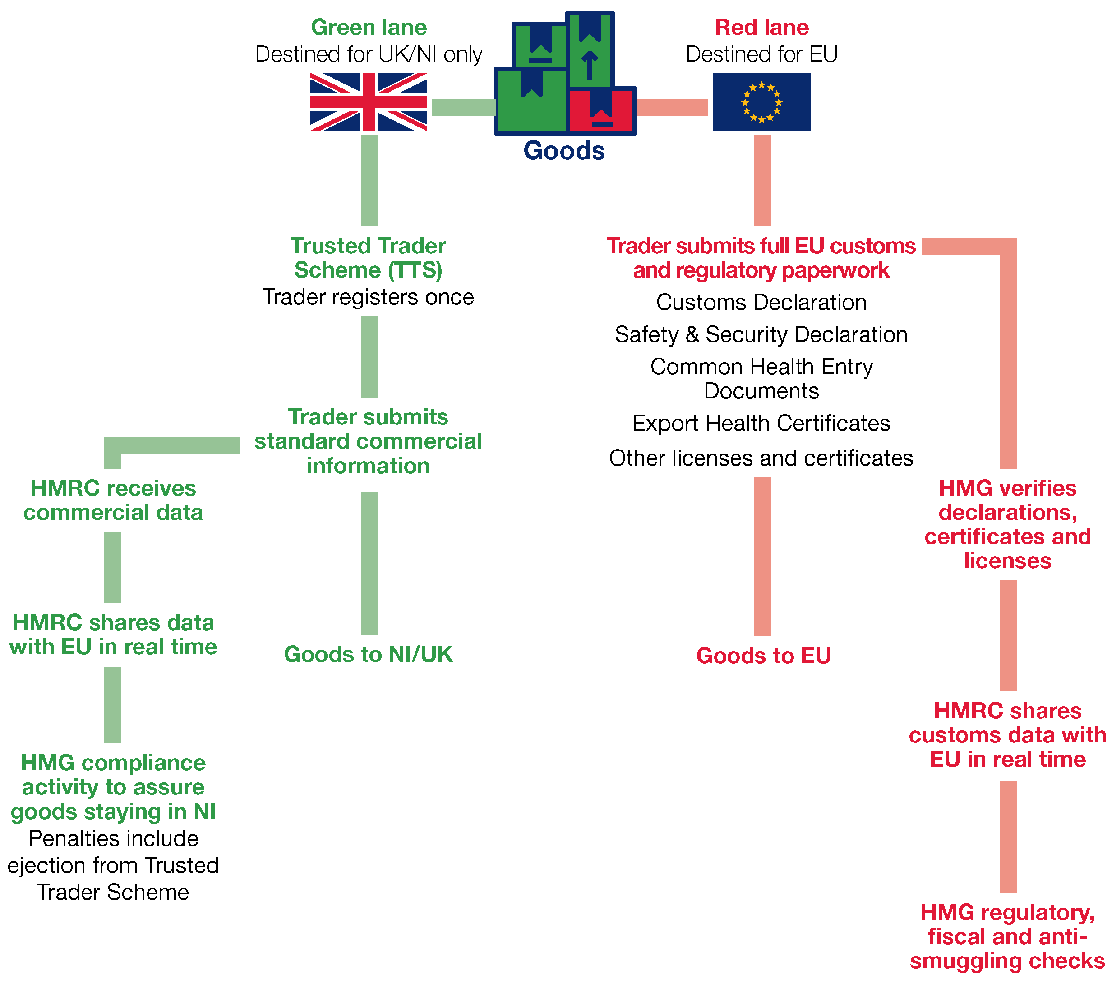

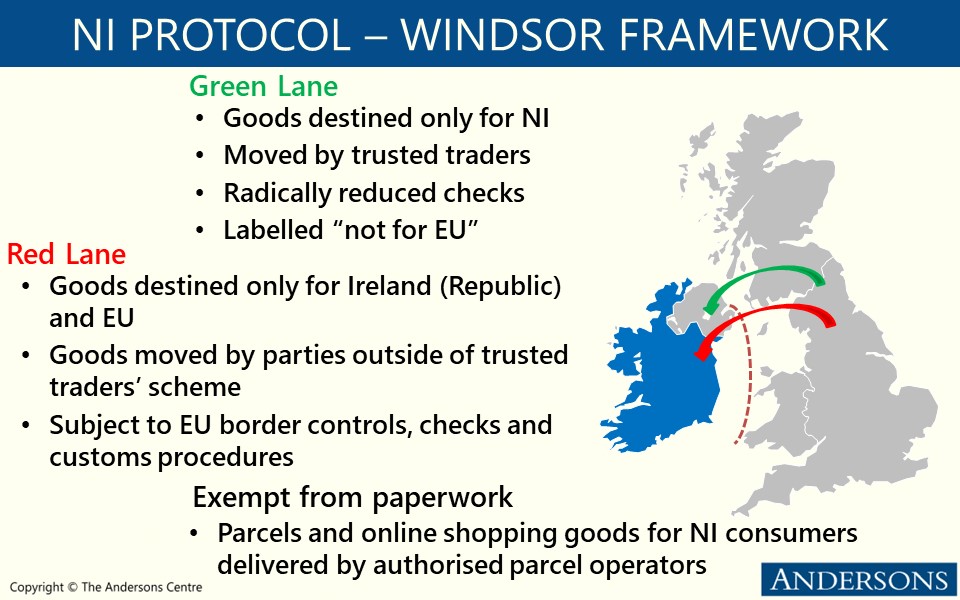

- Customs Procedures for Goods: there will be a ‘green lane’ for goods moving from Great Britain (GB) into NI which will be consumed in Northern Ireland and not deemed to be at risk of moving into the EU Single Market. For such goods, nearly all customs procedures will be scrapped. Goods deemed to be at risk of moving into the EU Single Market will be moved through a red lane, where EU border controls will apply.

- Chilled Meats: products such as sausages which are sold in GB supermarkets will also be available in Northern Ireland, provided that they are shipped into Northern Ireland by trusted traders. Chilled meats are usually prohibited from import into the EU Single Market or require arduous certification procedures (sometimes hundreds of certificates for a container with chilled meat and animal products for the retail sector). This will now be replaced by a single document confirming that the goods will stay in Northern Ireland and are moved in line with the terms of the UK’s internal market scheme. This is a significant concession from the EU. It is also a sensible one on the basis that such products are for consumption in Northern Ireland and there is now real-time data on the movement of goods from GB to NI, giving the EU the visibility it needs to ensure that no fraudulent activity is taking place. Any physical or identity checks that do take place will be on a risk and intelligence-led basis, based on decisions by UK authorities.

- Seed Potatoes, Plants and Trees: certain plant and crop products had been either prohibited from entry into NI from GB since January 2021, or required lengthy certification processes. Such trade can now recommence under the provisions of the Windsor Framework. This is seen as a big boost for the seed potato sector in particular. However, seed potatoes will still be prohibited from being sold to the Republic of Ireland.

- VAT and Excise Duties: the NI Protocol’s legal text has been amended so that the UK can set VAT and excise duties for the whole of the UK. It means that the reforms to alcohol duties taking effect in the UK in the summer will now apply to NI, thus lowering the price of beer in NI pubs for instance.

- Parcels and Online Shopping: no paperwork will be required for parcels moving from GB to NI.

- Pet Travel: documentary requirements and associated treatments and inoculations that are usually required by the EU have been removed for travel between GB and NI.

- Applicability of EU Law in Northern Ireland: has been reduced substantially (estimated by the NI Secretary to be 97%) and now only focuses on the ‘minimum necessary’ to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland. The EU notes that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) will still have a final say on Single Market issues. However, it is envisaged that its role will be greatly reduced due to the provisions outlined above and also because of the data sharing, labelling and enforcement procedures within the Windsor Framework. This will help to safeguard the Single Market whilst also giving opportunities to resolve differences without having to revert to the ECJ.

- ‘Stormont Brake’: this new mechanism is designed to give the Northern Irish Assembly the opportunity to pull an emergency brake on EU legislative changes which would apply in Northern Ireland. It is designed to address concerns, particularly amongst Unionists, on what they perceive to be a democratic deficit of the NI Protocol as agreed in 2020.

For the brake to activate, it would require cross-community support and would need a minimum of 30 Assembly MLAs from at least 2 parties to agree to its activation. The EU stresses that this can only be activated in exceptional and emergency circumstances, where there is a significant impact specific to everyday life in Northern Ireland. It is also planned to have greater consultation between the UK and the EU on new EU legislation so as to minimise instances of the Stormont Brake being activated. Once triggered, the UK Government would notify the EU of its activation. The rule in question would automatically be suspended from coming into effect. It could only then be reapplied if the UK and EU jointly agree. If the suspension remains, the EU reserves the right to respond with remedial action to protect its Single Market. For the Stormont Brake to become an option, it requires a functioning NI Assembly and is seen as a bid to get the NI Executive back up and running.

Overall, the Windsor Framework strikes a pragmatic and careful balance between the concerns of the UK Government and Unionists who wish to ensure that Northern Ireland remains an integral part of the UK, and of the EU in ensuring that its Single Market is protected. With hindsight, it was the sort of balance that should have been struck when the original Protocol was negotiated in late 2020, but which ended up being rushed and was negotiated without enough attention to the nuance needed for the unique circumstances of Northern Ireland. Importantly, by giving NI unfettered access to both the UK Internal Market and the EU Single Market, the Windsor Framework gives Northern Ireland the potential for strong economic growth, not just in agri-food but across NI industry generally. Undoubtedly, the Protocol will need further refinements in the years ahead as will the UK-EU trading relationship more generally. This is as it should be, as trading relationships between near neighbours are constantly fine-tuned. The US-Canada relationship is a prime example of this.

NI Protocol Deal

At the time of writing (morning of 27th February), it is expected that a deal will be imminently reached between the UK Government and the EU on the implementation of the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol. The European Commission President (Ursula von der Leyen) is travelling to the UK today for high-level talks with the Prime Minister to address the final list of issues which are said to require top-level scrutiny by both leaders.

It is said that the remaining issues centre primarily around the role for the Northern Ireland Assembly in having a say around how EU Law is applied in Northern Ireland. Some also suggest that there will be further discussion around the role of the European Court of Justice, although this is mainly seen as an issue for the European Research Group (ERG) within the Conservative Party.

Although both the UK Government and the EU have remained tight-lipped about the details of the deal, it is widely believed that the deal will remove checks for goods crossing from Great Britain (GB) into NI which are destined for Northern Ireland only. Key to achieving this has been the real-time access to shipments’ data on goods crossing from GB to NI which has enabled the EU to adopt a more flexible approach.

After meeting with Ursula von der Leyen, the Prime Minister will hold a virtual Cabinet Meeting to discuss the details of the deal (if agreed). From there, Rishi Sunak will then brief the House of Commons in the evening. Whilst the deal is imminent, there will still be significant hurdles to surmount including whether the DUP and the ERG wing of the Tory party will support it. However, Labour has said that it will support the deal. Many are hoping that this will be one of the last major moments in the Brexit saga. With numerous other challenges to tackle, all key stakeholders, particularly agri-food businesses are keen for these issues to be resolved so that there can be some certainty on trading arrangements between GB, NI and the EU in the coming years.

As soon as the text of the deal emerges, we will update readers via an online article.

NI Protocol Negotiations

Negotiations between the UK and the EU on making amendments to the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol have dominated the trade agenda in recent weeks. There have been promising signs of progress, although significant hurdles need to be overcome if an agreement is to be reached by April (to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the Belfast Good Friday Agreement).

The announcement, on 9th January, of a data sharing agreement between the UK and the EU is key development as it permits the EU to gain real-time access to data on goods movements between Great Britain (GB) and NI. The EU sees this as a critical pre-requisite towards rebuilding trust in UK-EU relations and in permitting the EU to consider introducing greater flexibility in how regulatory checks on goods coming from GB into NI are undertaken. However, this data-sharing agreement is only a first step and there are serious differences to reconcile in other areas.

Most notably, an agreement on the levels of Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Customs checks on goods remains unresolved. This is especially important for agri-food trade. Previously, the UK had proposed a ‘green channel’ at ports which would permit goods destined to stay in Northern Ireland to be waved through without customs paperwork. A ‘red channel’ would be set-up for shipments destined for the Republic of Ireland. This set-up would be complemented by a Trusted Trader scheme and fines to minimise non-compliance. Such proposals were dismissed by the EU as being insufficient to protect the integrity of its Single Market.

Back in October 2021, the EU proposed an ‘express lane’ for goods destined to stay in NI, although Customs paperwork would still be required. At the time, these proposals were dismissed by both the UK Government and the DUP as being unacceptable because of the border it would create on the Irish Sea which would undermine the integrity of the UK.

The current negotiations are focusing on finding a landing zone between the green channel and express lane approaches. If this conundrum could be resolved, a pathway towards an agreement between the UK Government and the EU should emerge. However, concerns persist as to whether the DUP would accept this. So, whilst the mood music has changed and progress is being made, it remains premature to expect an agreement yet. Talks are likely to continue until April and beyond. What might yet emerge is a ‘fudge’ based on more temporary arrangements similar to the extension of the grace period for checks on veterinary medicines traded between GB and NI agreed last month.

Trade Update

After a relatively quiet few months on the trade policy front, recent weeks have seen a resurrection of previous debates around the future long-term relationship that the UK should have with the EU as well as the impact of new trade deals that the UK is in the process of concluding.

Talk of a Swiss-Style Relationship

Following the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, rumours emerged from Government circles of a change in approach towards the long-term relationship that the UK would have with the EU. This would see it move towards something more akin to Swiss-style relationship. This would mean accepting free movement, contributions to the EU budget, dynamic alignment with EU regulations for goods, and European Court of Justice (ECJ) oversight in return for being part of the Single Market. Whilst some welcomed this, others claimed it was a betrayal of Brexit.

What many failed to acknowledge was that the EU is dissatisfied with how its relationship with Switzerland is structured as it requires more than 100 bilateral deals to replicate Single Market requirements and which constantly need to be renegotiated. It is unlikely to want to replicate this with the UK. In any event, the UK Government later denied that it was seeking to move to a Swiss-style relationship.

That said, and from an agri-food perspective, there is merit at looking at elements of the EU-Switzerland relationship and replicating aspects that make sense for both parties. In previous articles, we have advocated a Swiss-style Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) agreement with the EU, whereby the EU would permit frictionless access for UK agri-food goods in return for the UK dynamically aligning with EU regulations. Whilst previous Tory administrations (i.e. under PMs Johnson and Truss) dismissed this approach, it would appear that the Sunak administration is at least considering it.

Such an SPS agreement would greatly assist UK exports to the EU, its biggest trading partner and it would also overcome key hurdles in the ongoing NI Protocol negotiations, which have shown some tentative signs of progress recently. Whilst it would mean the UK mirroring EU laws, it would still leave scope, albeit more limited, for the UK to negotiate separate trade deals and trading arrangements, as the Swiss have done with the US. The UK could also give notice (e.g. of one year) if it wanted to discontinue this arrangement.

Overall, the talk of using existing templates in framing the future UK-EU relationship is becoming unhelpful. The sooner a bespoke UK-style relationship emerges the better. This could incorporate key aspects of other templates, but it will need to respect key EU principles, meaning that further negotiation is needed. It will also need to incorporate the closer relationship that NI will have with the EU, as it is de-facto part of the Single Market for goods by virtue of the NI Protocol.

Eustice Attack on Recent Trade Deals

On 14th November, during a House of Commons debate on the Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill, the former Defra Secretary George Eustice severely criticised the UK Government’s negotiating strategy for both trade deals. He singled out the then Trade Secretary, Liz Truss, for particular criticism, especially for imposing an arbitrary target of concluding negotiations with Australia ahead of the 2021 G7 summit. He thought that this severely weakened the UK’s bargaining power. Mr Eustice recalled that there were ‘deep arguments and differences in cabinet’, which were mirrored by friction between Defra and the Department for International Trade (DIT) during the negotiations. He also claimed that the ‘Australia trade deal is not actually a very good deal for the UK’ and that he tried his best when Defra Secretary to address its shortcomings. Specifically, he claimed that there was no need to give Australia (and New Zealand) unlimited access over the longer term for sensitive sectors such as beef and lamb.

From a farming perspective, it is all well and good to criticise the deal. But during his time in Government, Mr Eustice defended it – his comments, therefore, offer scant consolation to farmers who perceive these deals to be a significant threat. Both the Australian and New Zealand agreements will increase the competitive pressure on UK agriculture, particularly in grazing livestock. However, recent studies looking at the impact of these trade deals projected that the impact may be lower than some fear. That said, being the first new trade deals that the UK has negotiated from scratch since leaving the EU, they create an important precedent, and the cumulative impact of multiple trade deals can have a more significant impact.

The UK-Australia trade deal was ratified by the Australian Parliament on 22nd November. The Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill is making its way through Westminster. It is currently at the Report Stage, where amendments can still be made to the Bill, before a final third reading and subsequent vote on the Bill in the House of Commons – the date of which has yet to be announced. The House of Lords will also have to vote on the final Bill and they could delay it for up to a year before it would receive Royal Assent (assuming it is passed by the House of Commons).

EU Proposals on NI Protocol Flexibilities

On 15th June, the EU Commission published two position papers fleshing out its October proposals (click here for more detail) on the additional flexibilities that it could offer on the operation of the NI Protocol. In a widely expected move, the Commission simultaneously announced that it was unfreezing legal proceedings that it had initiated against the UK last year but halted in July 2021 to facilitate further negotiations on the Protocol.

The Commission’s position papers are aimed at providing solutions to key aspects of the impasse surrounding the operation of the NI Protocol on the movement of goods from GB to NI. These papers focus on Customs and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) rules respectively.

Customs Flexibilities

The Commission’s proposals seek to dramatically reduce customs formalities and costs for goods deemed not at risk of being subsequently moved into the (European) Union. Here, the EU proposes to widen the scope of the previously proposed Trusted Traders Scheme (UK Traders Scheme) to encompass more companies, including SMEs. This means that such traders would be regarded as shipping goods ‘not at risk’ of entering the single market.

The Commission also proposes that such traders could avail of a ‘super-reduced data set’. They claim that this would reduce the number of data elements on a customs declaration falling from 80 to 21. This would also include simplifying commodity code requirements (i.e, entries would be based on 8-digits as opposed to 10-digits). The need for supplementary declarations would also be abolished for such traders.

In addition, the Commission is also open to looking at added flexibilities where there is evidence that traders have been adversely affected by the implementation of the Protocol as well as further flexibilities for NI firms processing GB inputs.

SPS Rules

The Commission paper proposes that a much reduced regime of controls would be available to ‘authorised retailers’ operating in NI and their GB-based suppliers. These would be available to traders regardless of size and would be expanded to include the hospitality sector, schools, canteens, and supermarket distribution centres, on the proviso that the food would be packed and labelled for end consumers in Northern Ireland.

One notable proposal is that of a ‘single simplified official certificate’ being required for each lorry load of mixed retail goods. This certificate would be signed by a UK Competent Authority and would replace the potentially numerous official certificates that would be required for such loads if the Protocol was fully implemented in its current form. The Commission also claims that documentary checks could be performed electronically and that identity and physical checks could be reduced by 80%.

The Commission has claimed that these flexibilities will require changes to EU laws, including its sensitive food safety regulations. This would be subject to some preconditions and safeguards implemented on the UK side.

UK Government Reaction

Given the publication of its NI Protocol Bill a couple of days beforehand which effectively supplants the existing NI Protocol, it was unsurprising that the Government’s initial reaction was negative. It claimed that the implementation of the EU’s proposals would mean a worsening of the current trading situation (note: grace periods are still in place for some agri-food products). Also, despite the EU’s proposed facilitations for products such as chilled mince or sausages, Veterinary Certificates would still be required. Instead, the UK wants EU Member States to give the Commission a mandate to renegotiate the entire Protocol – something that the EU side is adamant will not happen.

Overall, whilst the EU Commission’s positions papers represent some movement, its latest flexibilities are still predicated on the October 2021 proposals. It is apparent that they do not go far enough for the UK side. Also, NI business groups, whilst seeing these position papers as a basis for further discussions, would like to see more flexibility from the EU side. The EU Commission has emphasised that it stands ready to re-engage in negotiations with the UK Government to solve the remaining Protocol issues. What is clear is that the basis of a ‘landing zone’ is visible. There is common ground between the UK Government’s green lane proposals in the NI Protocol Bill and the EU’s express lane approach, initially put forward last October. But, much more work is needed for both sides to reach common ground across all issues.

The EU Commission’s position papers are accessible via the links below;

- Customs – https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/protocol-ireland-northern-ireland-position-paper-possible-solutions-customs_en

- SPS – https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/protocol-ireland-northern-ireland-position-paper-possible-solutions-sanitary-and-phytosanitary_en

Northern Ireland Protocol Bill

On 13th June, the UK Government introduced the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol Bill to the House of Commons. The highly controversial Bill, if enacted, would dis-apply large swathes of the NI Protocol which was agreed between the UK and the EU as part of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiations. The Bill’s legal text which is highly complex and potentially far-reaching drew harsh criticism from multiple sources. It has been met with particular disdain by the EU which sees the Bill as a breach of international law and the Commission is set to respond in the near future. At a top-level, the Bill seeks to do three things;

- Disapplies large parts of the Protocol: relating to most provisions that apply EU rules on the movement of goods into NI.

- UK’s Protocol alternative: is outlined and the UK Government provides some guidance on how it would be implemented.

- European Court of Justice oversight: the Bill would remove the Court’s direct jurisdiction and the role for EU institutions

In essence, the Bill is effectively rewriting the Protocol, in a unilateral manner, outside of the structures agreed by the UK Government and the EU. Whilst the political fall-out will continue to generate intense debate, it is the accompanying policy paper which provides practical insights on how the Bill would work and the implications for agri-food. The key points are;

- Establish new ‘green channel’ arrangements for goods staying in the UK: it is claimed that this would fix the burdens and bureaucracy caused by the application of EU Customs and SPS rules. This channel would only be available to firms registered as ‘trusted traders’ and this scheme would be overseen by UK Authorities. Goods moving on to the EU or moved by firms not in the trusted traders’ scheme would use the ‘red lane’ and be subject to the full range of regulatory checks. This would significantly reduce the sometimes complex certification requirements for agri-food produce. Here, the UK proposals are not that far from the EU proposals published last October which suggested an ‘Express Lane’ for goods moved by trusted traders which would be consumed in Northern Ireland.

- Establish a new ‘dual regulatory’ model: this is intended to provide flexibility for NI firms to choose between UK or EU rules on product standards. It is intended to remove barriers to trade within the UK internal market and the UK Government claims that it will encompass robust commitments to protect the EU Single Market. For agri-food, goods could only move from GB to NI under the trusted trader scheme (otherwise they would be in the red lane and subject to checks). There would be robust penalties for violations. The EU strongly objects to this proposal on the grounds that it undermines the integrity of its Single Market. There are also challenges around the bureaucratic complexities involved with dealing with two regulatory systems. Major NI agri-food businesses are also against these proposals as it would scare-off overseas customers from purchasing NI produce as they would be unsure on which standards the products are adhering to and would be deemed too complex and risky.

- State Aid and VAT: the UK Government states that the Protocol restricts the UK from providing the same tax and spend policies in NI as the rest of the UK—with little room for flexibility. This aspect of the Protocol was insisted upon by the EU so that there was a level playing field between NI and the EU Single Market and that NI firms, or GB firms with operations in NI, did not gain an unfair advantage. The new Bill gives the UK freedom to disapply these rules so that NI can have the same tax rules as other parts of the UK. Again, the EU strongly objects to these proposals.

- Role of European Court of Justice (CJEU): would be removed in dispute settlement and would provide the means for UK Authorities and Courts to set out the arrangements which apply in Northern Ireland. This is also highly controversial from an EU perspective as it would not have agreed the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the UK if the CJEU did not have ultimate oversight over the NI Protocol.

Whilst the full EU response is awaited, it has confirmed on 15th June it is restarting the legal proceedings it had initiated last year against the UK Government for its unilateral extension of grace periods for checks on products such as sausages and mince. These had been suspended for almost a year to facilitate negotiations on addressing the Protocol issues. The EU response is also likely to state that it reserves the right to enact much more stringent measures if this NI Protocol Bill becomes law in the UK. This would include suspending key aspects of the TCA or introducing some tariffs on UK exports to the EU. That said, the EU will also be keen to get the UK back to the negotiating table and the Commission has set-out further proposals on how it thinks the outstanding issues on the NI Protocol should be dealt with.

From an agri-food perspective, it is important to note that the House of Lords will vote against this Bill, thus delaying its enactment for at least a year. This gives time for further negotiations to take place. However, additional negotiating time has been wasted in the past. Breaching International Law (which legal experts almost entirely agree would happen if this Bill were to be enacted)) is not the way to build trust. What is needed now is quiet and determined diplomacy to reach a deal that all parties can live with.

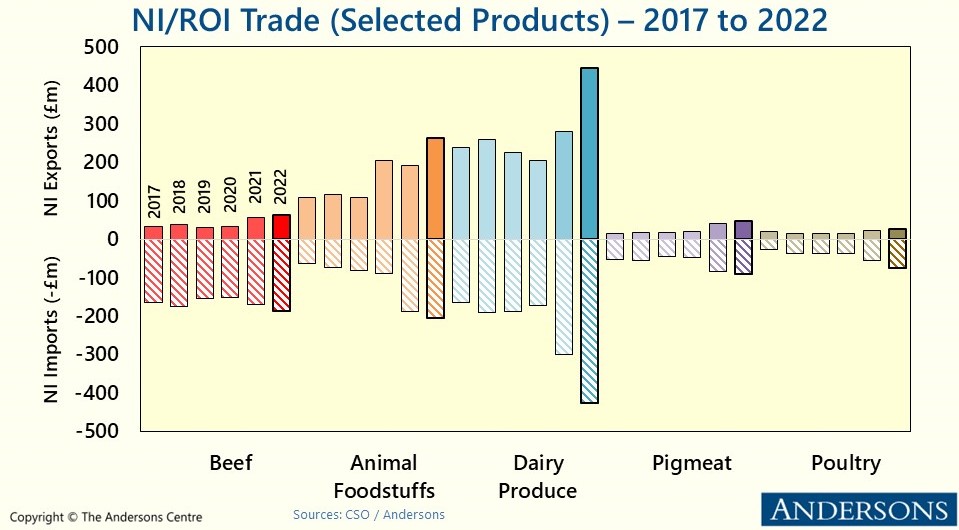

NI agri-food businesses are adamant that the Protocol delivers major benefits in enabling NI to access the EU Single Market whilst having unfettered access to GB. As we have mentioned previously, a UK-EU veterinary agreement would help greatly to reduce the burden of checks, not just GB to NI but also GB to the EU. On this, the EU needs to be more flexible. The UK will not opt for a Swiss-style veterinary agreement as that would mean following EU rules for the whole of the UK. A bespoke veterinary agreement should be a key part of the framework to resolve the remaining Protocol issues.