The Scottish Government has published a study on the impact on Scottish agriculture of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) between the UK and four selected non-EU partners, namely: Australia; New Zealand (NZ); Canada; and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). It found that these free-trade deals could have a significant negative impact on certain sectors of Scottish farming, particularly sheep. The study was undertaken, in 2022, by Andersons and Wageningen University and Research (WUR).

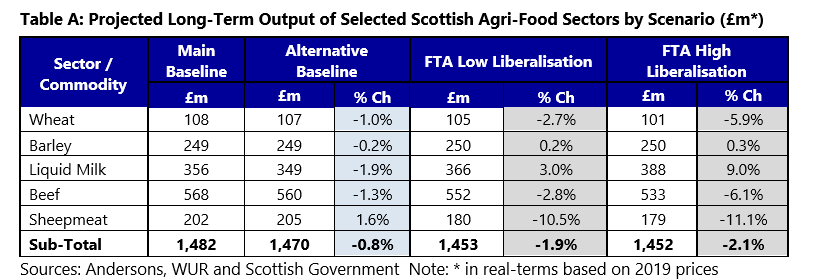

The study quantifies the FTA impacts on selected Scottish agricultural sectors namely: cereals (wheat and barley); livestock (dairy, beef, and sheep); and potatoes. This was done using two FTA scenarios; high and low liberalisation. These were modelled alongside the current status quo (UK has left the EU but the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is in place). An Alternative Baseline (No-Brexit) scenario was also briefly examined.

The research was undertaken in collaboration with Wageningen University and Research (WUR) and used a combination of MAGNET, a computable general equilibrium economic model to assess the individual and aggregated impacts of each FTA, as well as desk-based research and interviews with industry experts based in Scotland, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the Gulf region.

Key Results

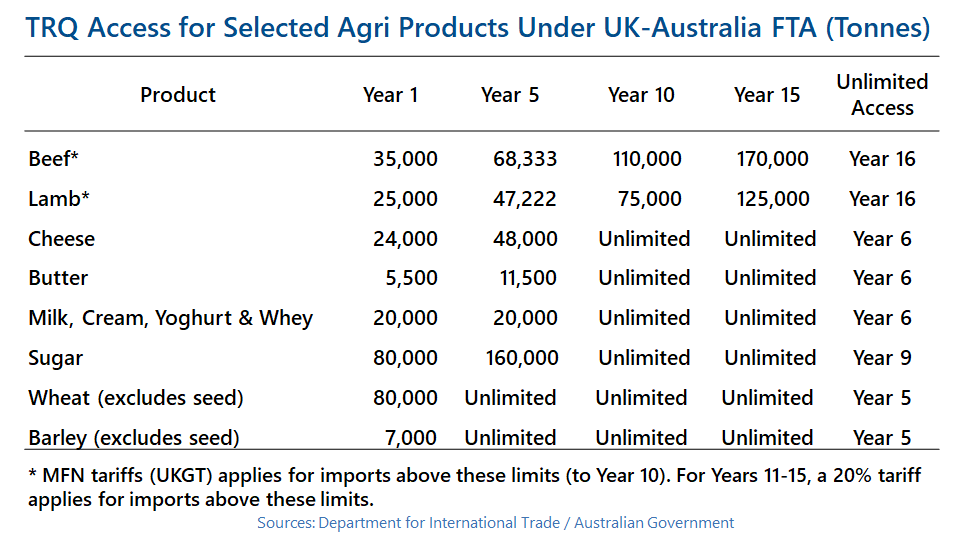

- Impact of the selected FTAs is generally limited, but significant in some sectors: as Table A depicts, the projected long-term impact of the FTAs on Scottish output is relatively small in most cases. The exceptions are sheepmeat, where output is forecast to fall by around 10.5% to 11% under the Low and High Liberalisation scenarios. Beef and wheat are also projected to fall (both by around 3% to 6% depending on the scenario). Conversely, liquid milk output is forecast to grow by 3% to 9% in value terms, indicating significant FTA opportunities for dairy products. Barley is forecast to show a small long-term gain.

- Cumulative impacts of future FTAs will be more significant: although the aggregated impact of the selected FTAs is relatively limited, the cumulative effect of multiple trade deals over the longer term should not be underestimated. This is especially so if the UK agrees FTAs with agricultural powerhouses such as the US and Mercosur (including Brazil and Argentina).

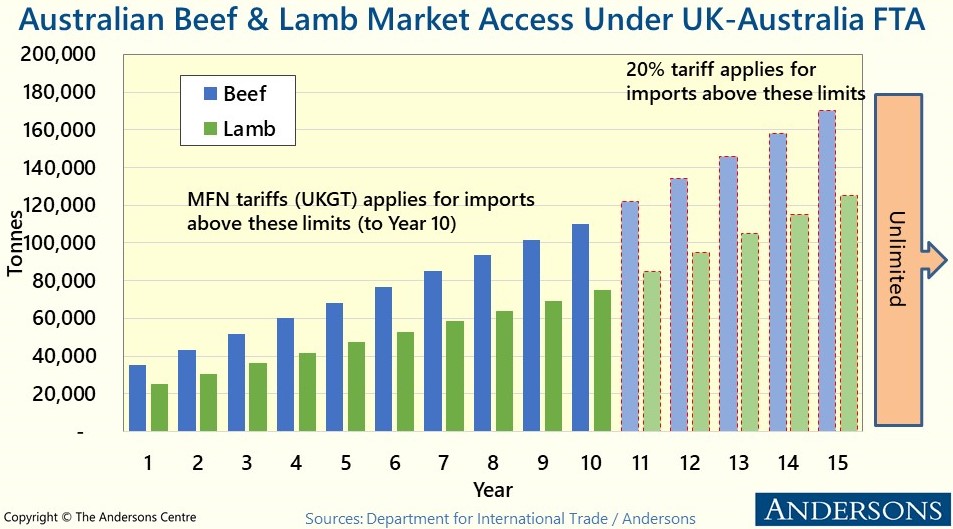

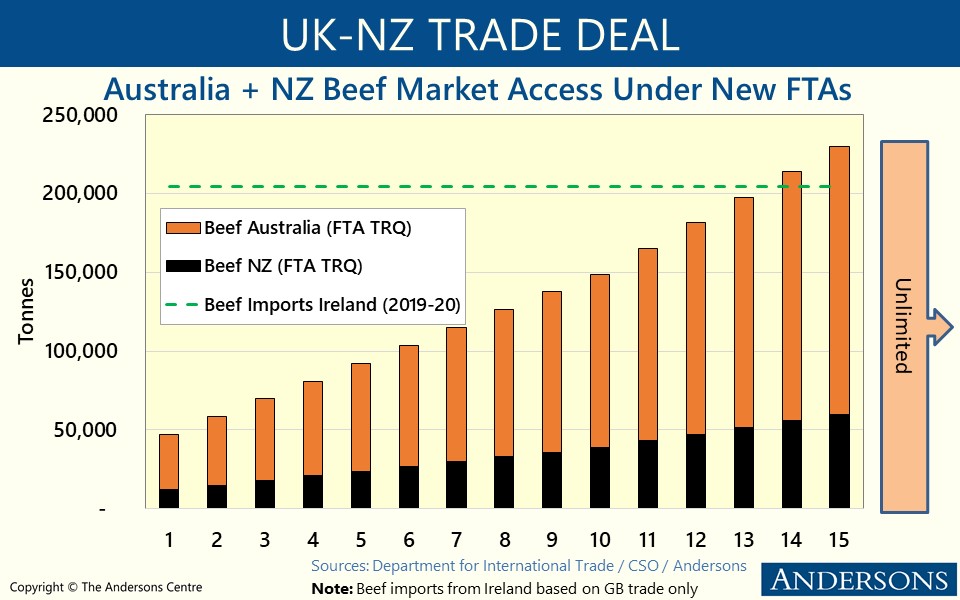

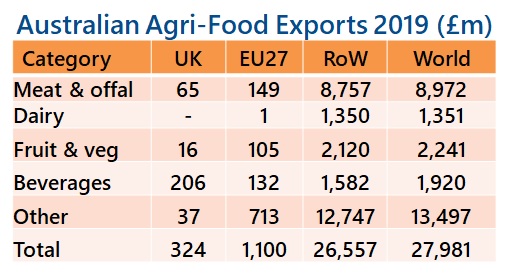

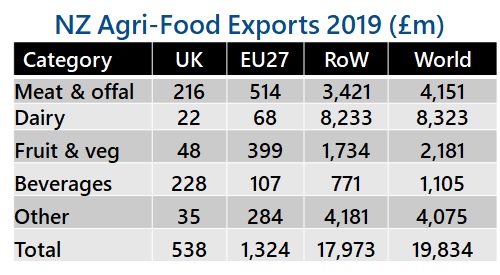

- FTAs with Australia and NZ are main drivers of declines Scottish sheepmeat output: the new FTA is seen by many as a strong signal for NZ businesses to recapture trade with the UK, which was lost when the UK joined the EEC. Australia will also be keen to increase sheepmeat exports to the UK.

- Beef sector will come under pressure but some opportunities also exist: whilst imports from Australia and NZ will create more competition, a trade deal with Canada is likely to generate some export opportunities. Given the brand recognition of Scotch beef, it should be relatively well-positioned to exploit such niches. That said, safeguarding domestic sales, particularly to UK retailers, from overseas competitors will remain most crucial.

- The FTAs with Australia and NZ set important precedents: the recently agreed FTAs with Australia and NZ give important signals to other countries on what the UK is willing to cede in trade negotiations. Therefore, the standards that the UK is willing to accept for imports is pivotal, especially as other FTA partners will likely push for more concessions during negotiations. Any significant changes to standards relating to food safety and hygiene, the environment and animal welfare will have major implications for Scottish produce. This is not just on the home market, but overseas as well, especially in terms of highly-renowned brands such as Scotch Beef.

- FTA opportunities for dairying the dairy sector is best positioned to see export growth, particularly to the GCC, where Scottish dairy produce has already gained traction in high-end segments. UK exports to GCC in 2018-20 are valued at £38m and could rise by as much as 49% in a High Liberalisation scenario. Opportunities theoretically exist to export to Canada, but, as it is highly protectionist, sales are likely to be limited to select niches.

- Long-term impact of Brexit is deemed to be limited: Table A also shows relatively small differences in output under the Main Baseline (incorporating Brexit) and the Alternative Baseline (No-Brexit scenario). Although seed potatoes were not modelled, the loss of the EU markets for Scottish seed potato exports is significant and the restoration of this market access is a key goal for the sector. It should also be a primary objective for policy-makers.

- Significant Farm Business Income (FBI) declines: of up to 60% in some sectors, in both the Main Baseline and FTA Scenarios in comparison with the Base Year (2019/20) although the differences between the Main Baseline and FTA scenarios are quite small. This is chiefly linked with declining prices.

- New FTAs to have negligible impact on potatoes: industry input suggests that the new FTAs will have minimal impact on seed potatoes’ profitability. Instead, the impact of the loss of the EU market for Scottish seed potatoes is estimated to have led to a decline in seed potato prices of approximately 4%. Restoring market access to the EU27 and Northern Ireland is a priority for the sector.

Overall, the findings that more pressure will be exerted on the Scottish (and UK) beef and sheepmeat sectors are unsurprising as Australia and New Zealand are widely regarded as significant and highly competitive players on the world markets. That said, the projected extent of declines on output is perhaps not as pronounced as some might have feared, although the declines are still significant. The report also suggests some opportunities for dairy products, particularly in the Gulf region.

The Summary Report is available on the Scottish Government website via: https://www.gov.scot/publications/analysis-impact-future-uk-free-trade-agreement-scenarios-scotlands-agricultural-food-drink-sector/