UK Combinable Crop Harvest – What Should We Expect?

The harvest is in its early stages; for some the oilseed rape and barley is gathered, for others it has just been desiccated or is still ripening. At this stage of harvest, without fail, commentators remark on the high variation of yield and quality. The first fields always show variation in performance, and even in consistent years, the first fields present an unreliable bellwether for the rest of the harvest. This is particularly as light southern soils often reach harvest before the heavier soils, and show greater yield variation, especially in years when drought has played a part in the year. It would astound us if overall the combinable crop yields turned out high, especially the winter crops. A good average yield of any of the main crops this year would either reset our expectations of what nature is able to do with plants in highly uncompromising conditions, or lead us to question the reliability of those calculating national estimates.

OSR

There will of course be some fields which just avoided being replaced in the spring, and harvest barely enough to justify the combine entering the field, but other fields will provide good crops. Like all other crops, it is too early for any meaningful analysis.

Remember, the standard FOSFA contract for oilseed rape is for 9% moisture. Oilseed rape is not accepted at moisture levels above 10% (or drying charges are incurred). There is a gain of 1% in price for every 1% the moisture decreases to 6%.

Cereals

Some traders consider the winter barley harvest is 75% completed already (not the case round here by a long way – Ed). Exports are taking place, both physical shipments and also orders. UK feed barley is cheapest in Europe at the moment. The demand for barley as animal feed (barley is generally for ruminants) seems to have dropped across some nations as people eat out less and therefore rely on white meats and vegetables in the home. Demand for barley is thus down a bit.

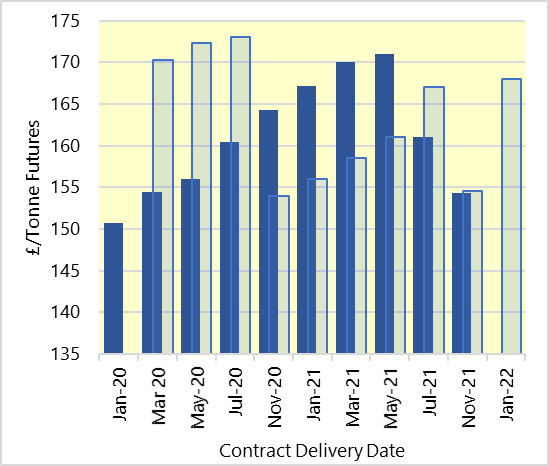

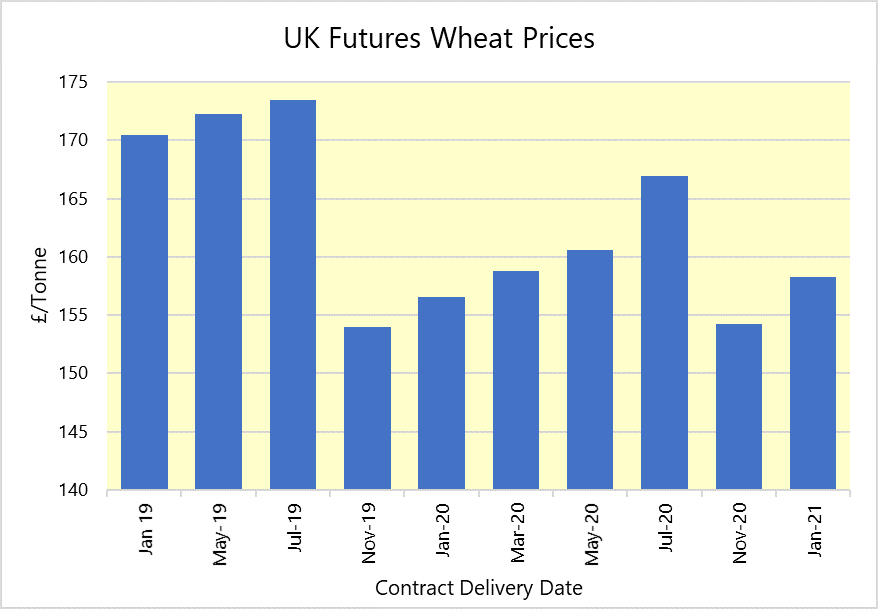

Over the course of the last year, the price of wheat for this harvest has been gradually rising, albeit with considerable fluctuations from £140 to almost £170 per tonne on the futures market. The prices for the 2021 harvest have remained highly range-bound between £150 and £155 per tonne. The slowly declining UK and European crop size has been evident throughout the year, so prices have picked up, but so far of course, the crop for 2021 is unknown.

Globally

Most combinable cereals are grown in the Northern Hemisphere, so our harvest time will be more or less in line with most others. Across the EU, harvest is quickly moving northwards. In France and Germany, the two main grain producing countries, harvest is progressing in an average condition (not as well as last year). The Russian wheat yield is reported as the smallest for at least 6 years, and smaller than initially projected.

Marketing

When it comes to marketing combinable crops this year, the focus may need to be more on the impacts of a Brexit than the actual marketplace itself. Yes, we acknowledge similar comments were made following last season’s harvest and nothing happened, but Brexit has now occurred, and more importantly, a new trading situation will be implemented as of January next year. This could possibly be trade with the EU without a trade deal. These factors will affect the value of the marginal tonne (either exported or imported) which sets the price in the whole market. We do not know the outcome yet, but farmers might consider this when planning on the date they fix the price of their grain (not necessarily the date of delivery).