With the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in place, attention will increasingly shift towards Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with non-EU countries. These can be divided into two broad categories;

- Rollover FTAs: these are agreements that the UK had access to when it was an EU Member State. In recent weeks, there has been significant progress. To date, the Department for International Trade (DIT) has already completed agreements with 63 countries, 60 of which became effective from 1st January. The other 3 (Canada, Mexico and Jordan) have been partially applied. This is an impressive feat considering the enormous challenges associated with Brexit and Covid-19. Discussions continue with 6 more countries including Serbia and Ghana.

As our previous article noted, although the negotiation with Japan was technically a ‘new’ FTA negotiation, the deal is essentially a rollover of the existing EU-Japan Partnership agreement. The UK-Japan agreement has some slight adjustments in terms of UK access to Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) and market access for products such as cheese.

- FTA Negotiations Underway: before the end of the Transition Period, DIT was already focusing on progressing FTA discussions with several countries. From an agricultural perspective, the most notable of these are the US, Australia and New Zealand. These negotiations will need to be watched closely as 2021 progresses.

Although the US trade deal negotiations get the most attention, progress may dissipate somewhat during 2021 as the Biden administration will have other priorities to deal with. However, talks will continue particularly as the UK-EU TCA has largely safeguarded the Good Friday Agreement – a key ‘red-line’ for the US.

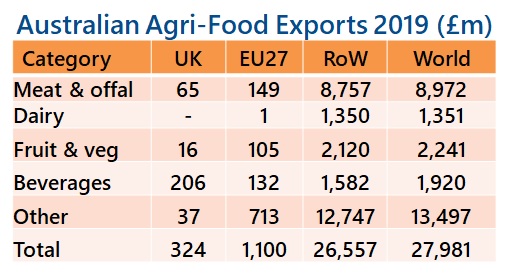

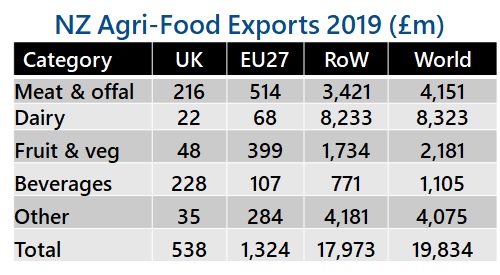

Perhaps the negotiations which are most likely to conclude in 2021 are those with Australia and New Zealand. As the tables below show, both countries are major exporters of meat (beef and lamb), dairy products and wine. A trade deal with these countries will exert the most pressure on UK grazing livestock. Admittedly, imports of beef and lamb from both countries into the UK and EU have been below historic levels recently. This is mainly a function of a greater emphasis being placed on the Asia-Pacific region. However, if the UK agrees a FTA with these countries it will lower trade barriers significantly versus current arrangements which operate via TRQs and standard WTO terms.

Sources: Sources: Australian DFAT / NZ Government / Andersons

Australia has been particularly eager to progress trade negotiations with the UK. Given the relatively high prices achievable in the UK, there is the potential for exports to be diverted from Asia-Pacific towards our market, particularly as China starts to recover from African Swine Fever and produces more of its own meat. From an agri-food perspective, export opportunities to both countries are limited to niche areas. Instead, the UK will use access to its food market as leverage to secure gains for its automotive and digital services sectors.

Longer-term, it inevitable that the UK will seek FTAs with other countries which will also exert significant competitive pressure on British farming. Chief amongst these would be an FTA with Mercosur, which includes Brazil and Argentina – – both beef exporting powerhouses. In recent years, Brazilian beef prices have been £1 per kg or more below the UK price. So, whilst the UK might be a net importer of beef presently and there is some scope for prices to increase given the frictions now placed on imports from the EU, future FTAs with non-EU countries have the potential to torpedo such gains, given the large price differences.

The agri-food industry needs to play close attention to the progress of new FTAs during 2021 and beyond, as they will have a huge influence over the future direction and competitiveness of British farming. The Trade and Agriculture Commission (TAC) set-up by the UK Government in July 2020 to examine the impact of new trade deals on UK agriculture will have a central role to play. However, it remains to be seen how much influence it will have in practice as Parliament will have the final say.