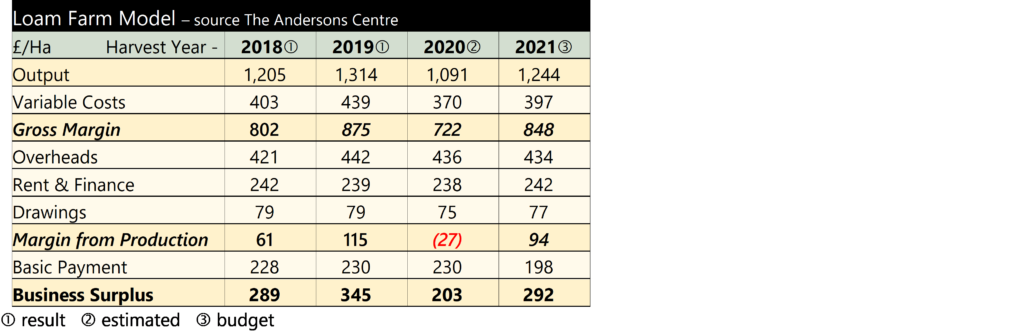

Despite the absence of a physical Cereals Event this year, Andersons have updated their Loam Farm figures as is usual at this time of the year. Not surprisingly, the financial prospects for harvest 2020 are not looking too great and this has prompted a change of cropping policy for 2021.

Loam Farm is a notional 600 hectare business that has been used since 1991 to track the fortunes of British combinable cropping farms. It is partly owned and partly rented and is based on real-life data. The latest figures are shown in the table below – illustrating the performance the farm has achieved for the past two harvests, and the prospects for the coming season and the one following that.

In 2018, yields were affected by the summer drought, but higher prices partly compensated for this. Extra costs meant that returns from farming were at least positive, but lower than had been seen in earlier years. The 2019 harvest saw yields exceed expectations. With reasonable sale prices (a mix of forward selling and spot sales through to spring 2020 when markets moved upwards) profitability improved despite an increase in both variable and overhead costs.

The upcoming 2020 shows the effects of the unusually wet autumn and winter. The standard cropping on Loam Farm has been 150 Ha each of feed wheat, milling wheat, oilseed rape and spring beans. This year only 70 Ha of feed wheat and 80 Ha of milling wheat got planted. The usual 150 Ha of oilseed rape was drilled, but 50 Ha was ripped-up this spring as it had failed. Spring plantings were unusually high with 200 Ha of spring beans and 150 Ha of spring barley going in.

As well as planted areas, projected yields have had to be altered in the budget as well. Both winter wheat and oilseed yields are lower than the farm would traditionally expect. As a positive, crop prices are reasonably firm – although the large area of barley planted nationally means a big discount to wheat. Also, costs have been saved due to a less intensive spray programme. Fuel has also been cheap this spring and some stores (seed and fertiliser) have been retained for next year. Even so, the weather has had a significant effect on budgeted farm profitability – pushing the business into a loss-making position from its farming operation. It is reliant on the BPS for overall profit.

Looking to 2021, the farm has decided to make a significant cropping change. It has been decided that OSR is no longer viable and too risky with front-loaded costs. A new rotation has been planned – 200 Ha 1st feed wheat; 100 Ha 2nd milling wheat; 100 Ha spring barley; 100 Ha spring beans; and 100 Ha winter oats. This means the farm has 1/3 spring cropping, helping control grassweed issues and spreading workload. With the change of cropping policy (and poor cashflow from harvest 2020) it has been decided to ‘pause’ machinery investment for a year. One side-effect of moving away from oilseed rape is that more grain storage is required. The cost of investing in an expanded grain store is included in the figures.

The dip in profitability for 2020 caused by a ‘difficult’ season can clearly be seen. At present, the BPS is available to smooth-over such problems. The phase-out of the BPS poses challenges to Loam farm and the many businesses like it to do something different. Loam Farm has been proactive with cropping changes to make itself more resilient in the face of potentially more difficult business conditions ahead. With change undoubtedly coming, those businesses that grab a head-start in improving efficiency will be best placed to prosper in the new environment.

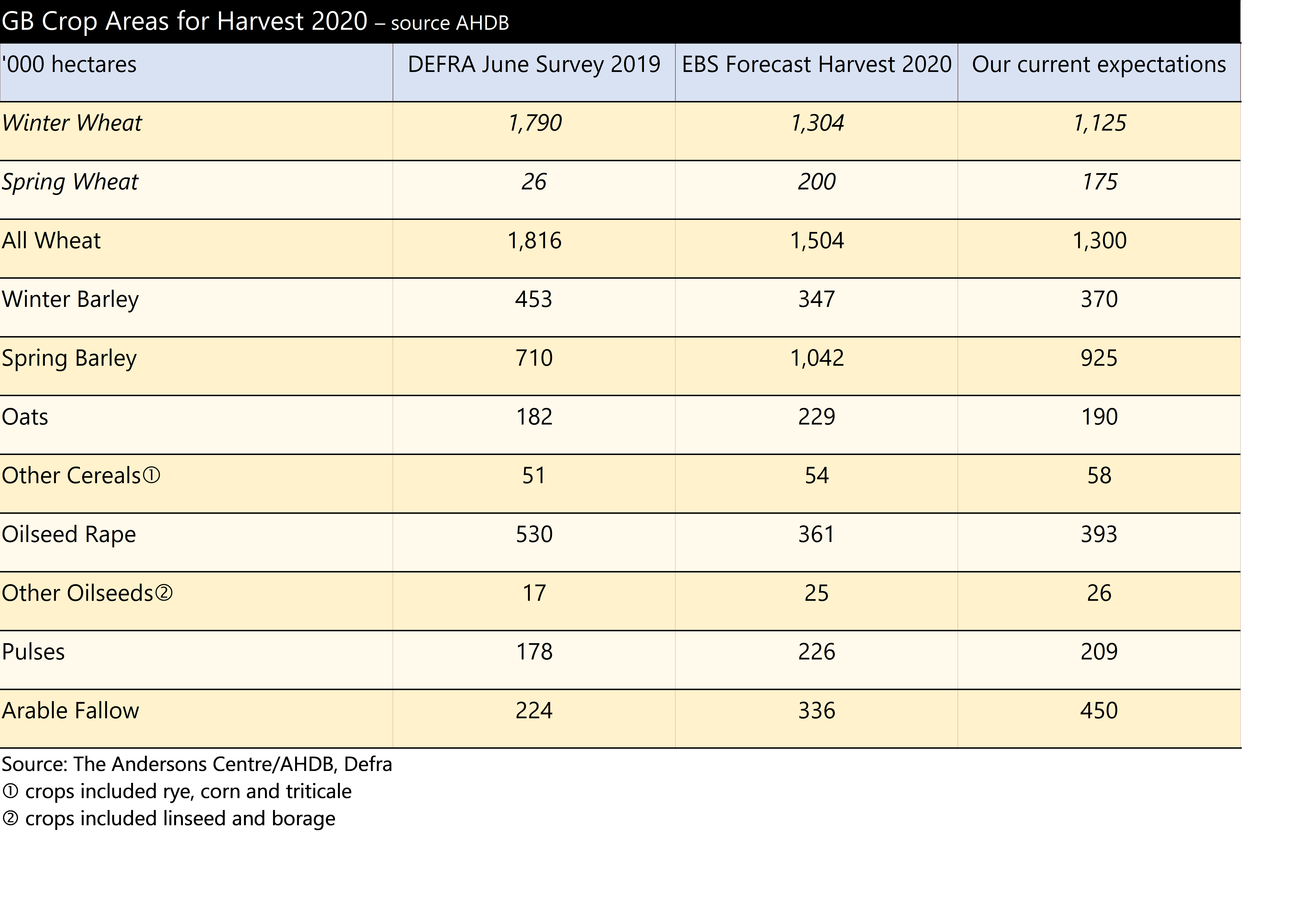

If this projection is correct, it would leave potentially the lowest wheat area planted in the UK since 1978/79, and the highest spring barley area since 1987/88. Some projections expect spring barley to exceed 1 million hectares but we are not convinced there is enough time for that to occur. Oilseed rape area might end up being the lowest since 1988/89. Even so, it still might be the highest we see again because the difficulties of growing the crop this year have been only partly because of the rain, and partly because of the flea beetle. The fallow land area we have suggested here would be the highest level since set aside was mandatory back in 2007. For 2020 autumn drilling and the 2021 harvest, we would expect a high proportion of farmers very keen to capitalise on the first wheat opportunity, possibly planting a little earlier than this year too. Hold tight for a big wheat crop next year.

If this projection is correct, it would leave potentially the lowest wheat area planted in the UK since 1978/79, and the highest spring barley area since 1987/88. Some projections expect spring barley to exceed 1 million hectares but we are not convinced there is enough time for that to occur. Oilseed rape area might end up being the lowest since 1988/89. Even so, it still might be the highest we see again because the difficulties of growing the crop this year have been only partly because of the rain, and partly because of the flea beetle. The fallow land area we have suggested here would be the highest level since set aside was mandatory back in 2007. For 2020 autumn drilling and the 2021 harvest, we would expect a high proportion of farmers very keen to capitalise on the first wheat opportunity, possibly planting a little earlier than this year too. Hold tight for a big wheat crop next year.