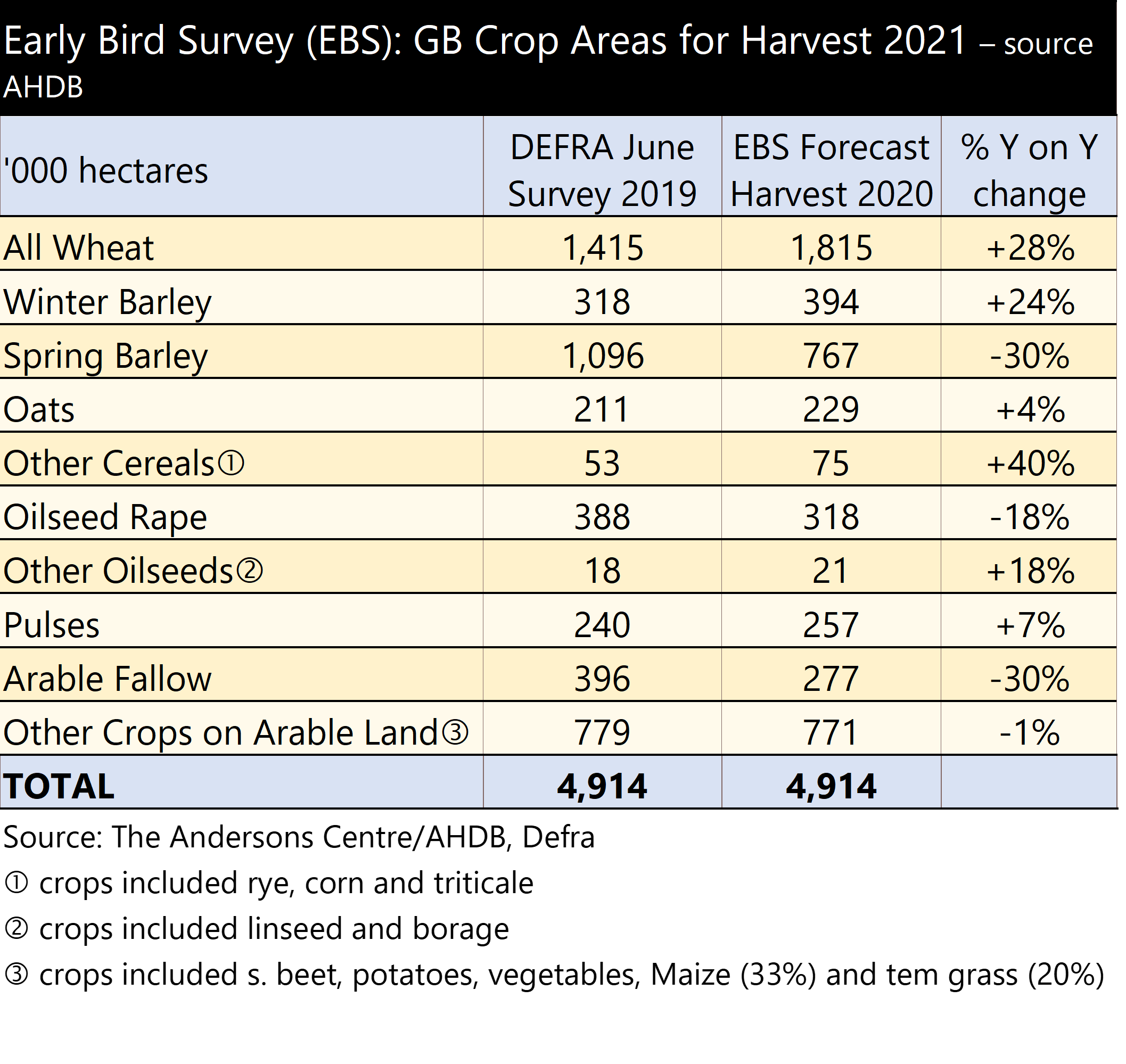

The harvest is in its early stages, with approximately a third of the winter barley in the Southern regions cut so far (it was three quarters this time last year). At this stage of harvest, high variation of yield and quality is easy to observe. We will refrain as the first fields present an unreliable bellwether for the rest of the harvest. This is particularly as light southern soils often reach harvest before the heavier soils, and show greater yield variation, especially in years when drought has played a part in the year. However, reports from most regions suggest that conditions are good, yield potential remains high and certainly far better than last year for most growers.

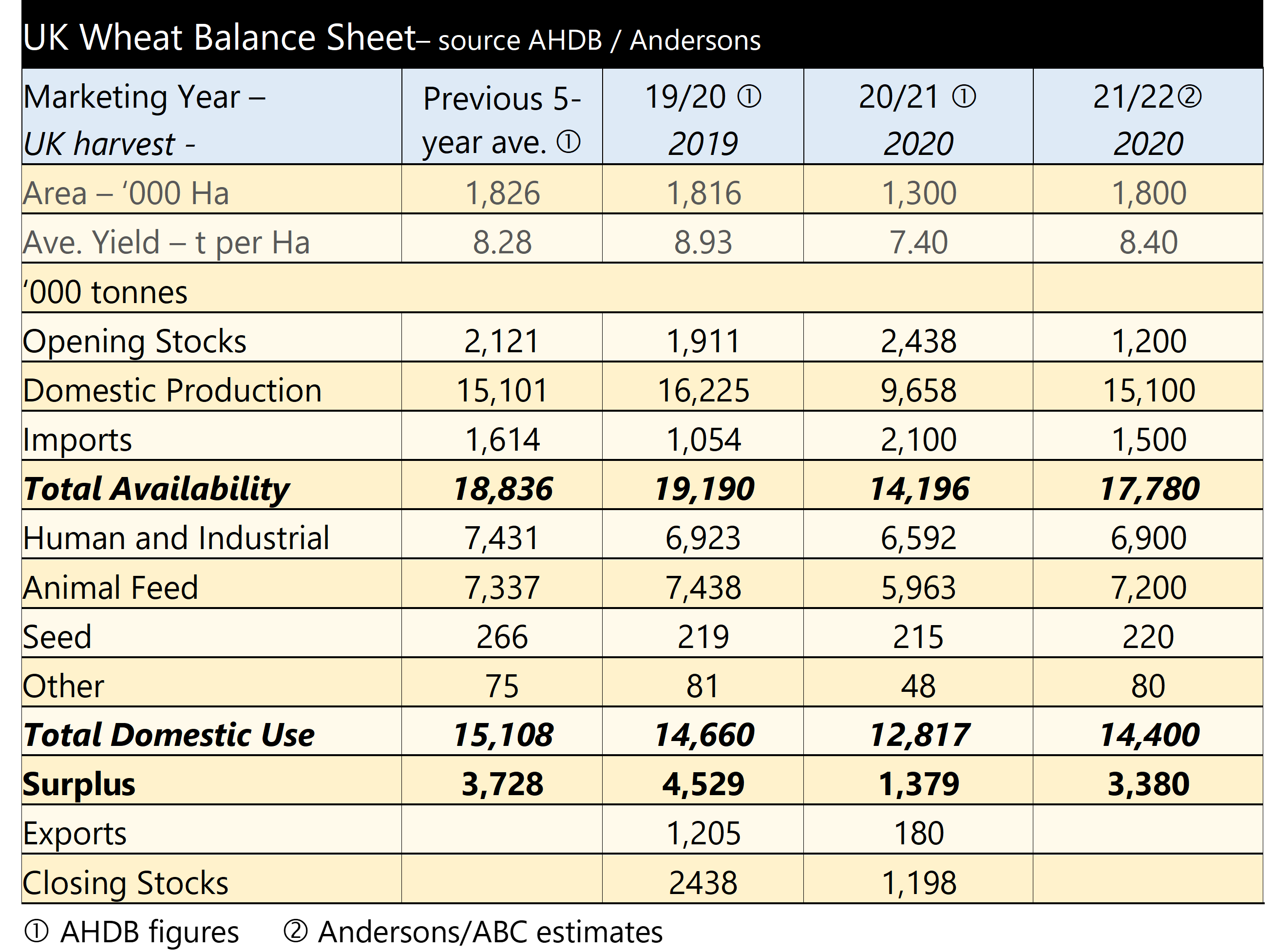

UK wheat markets have risen by £5 over July, but it has been an up and down month. This has taken other crops with it overall. Across the world, harvest is moving North. Most winter wheat in the US has been harvested now. The springs in northern USA and Canada will be next. These crops are parched and yields are expected to be low. Yields across Europe are generally good though.

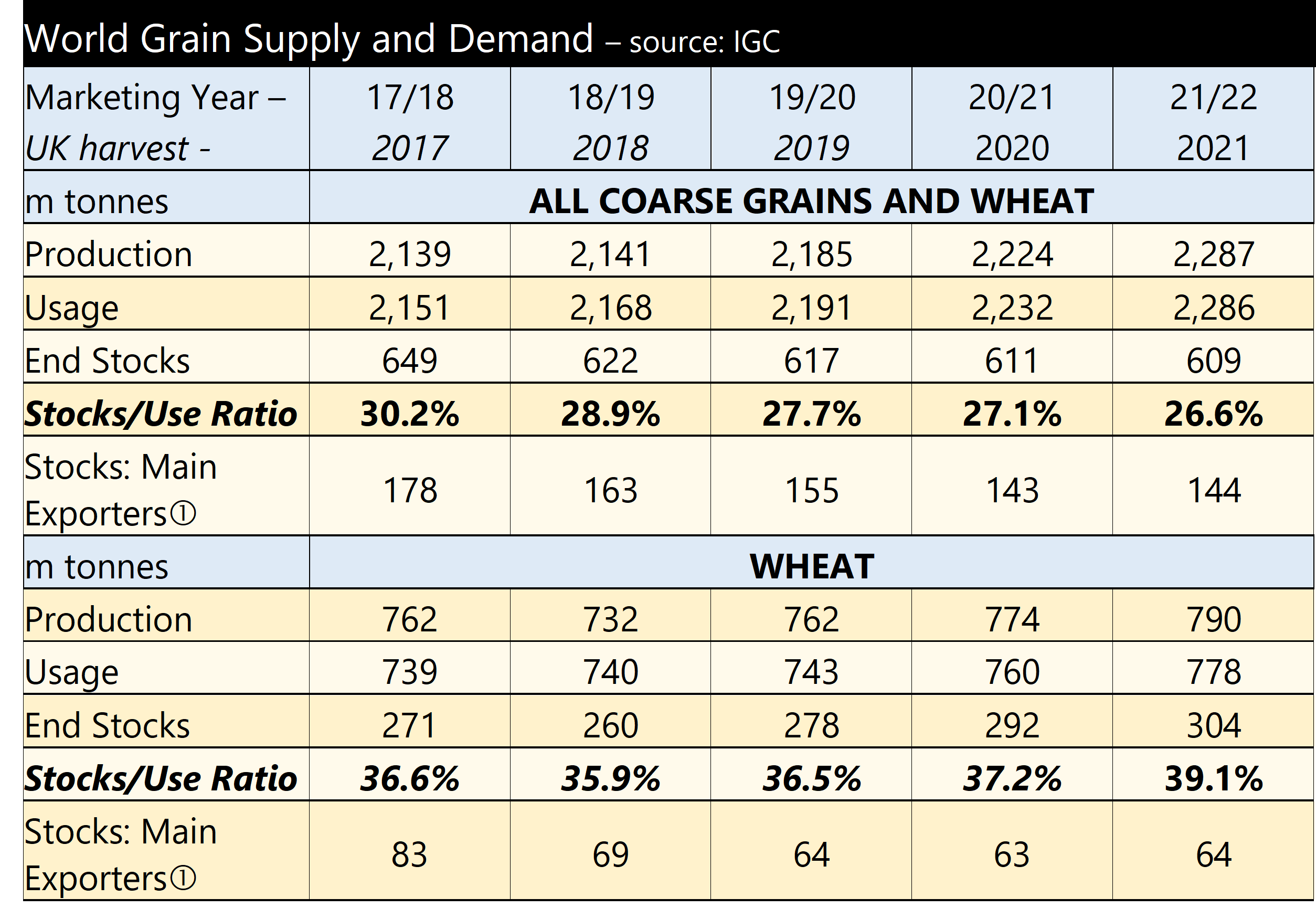

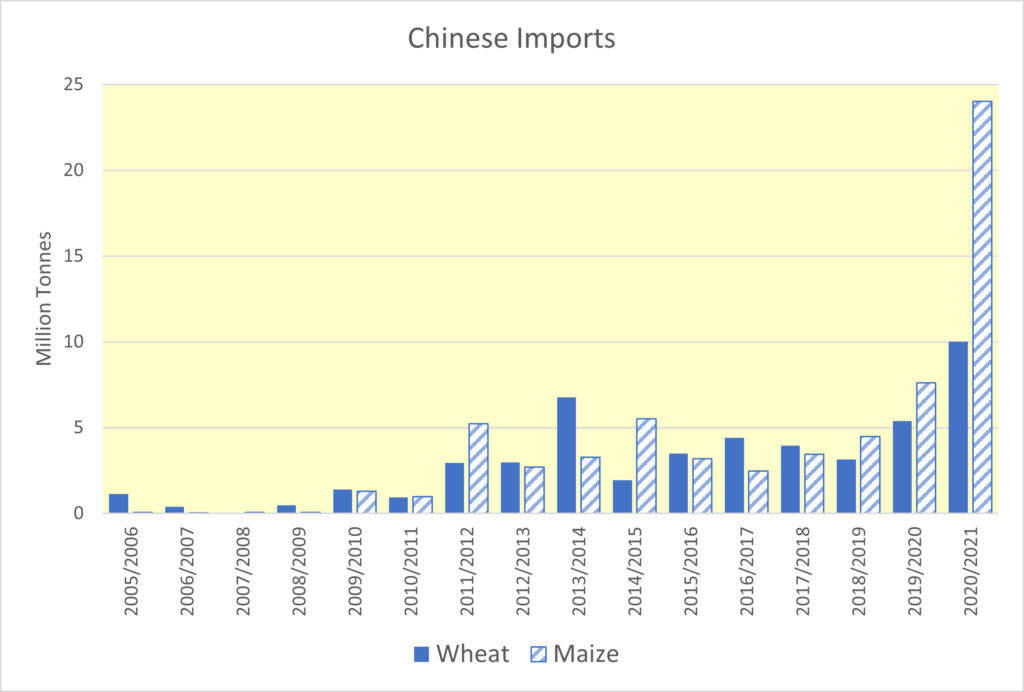

Every July/August, the world looks carefully to see how closely harvest matches demand and earlier projections. We hear about dry conditions around the world and the fragility of the food supply chain comes to mind. The harvest in the Northern Hemisphere over the next two months being so critical to the survival of the ever-growing population. There is no room for complacency and severe global drought would indeed cause problems across many countries (half of all grain stocks are hidden in China). However, a number of economists have been proven wrong throughout history by projecting the inability of agriculture to meet the needs of its population. Currently, stock levels and crop conditions are good and the first real indication of such a situation would be a strong rise in grain values. This is not happening as we move from old crop (import parity) to new crop (export parity), with the associated price adjustment as we move to exporting wheat again.

Oilseed rape harvest is pressing on, whilst the price is being pulled by good soybean crops in America (North and South) and very dry Canadian OSR/Canola crops. Within a month, this will be cut and the impact will be assessed rather than estimated or forecast which is what the currently fluctuating markets are based on.