Tag: Trade Deal

EU-Mercosur Trade Deal Negotiation

After more than two decades of negotiations and false starts, the EU and Mercosur (a South American trade-bloc consisting of Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay) concluded negotiations on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) on 6th December. Whilst it is the biggest FTA negotiation that the EU has ever concluded, and despite the environmental safeguards now built-in which hindered the deal in recent years, there are still several hurdles to overcome before the deal would enter into force. That said, the conclusion of negotiations is notable and the FTA would have a significant impact on EU agriculture if enacted. It would also have indirect implications for the UK.

The key provisions of the agreement are:

- Market access: significant tariff reductions for agricultural exports from Mercosur to the EU, with quotas introduced on more sensitive products (see next points). There will also be export opportunities for EU agricultural sectors like wine, spirits, and dairy products into Mercosur markets.

- Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) for Mercosur exporters to the EU:

- Beef: 99 Kt of carcass weight equivalent (CWE), of additional quota for Mercosur exports to the EU, subdivided into 55%fresh and 45% frozen with an in-quota tariff rate of 7.5%. There will also be an elimination of the existing in-quota rate in the Mercosur-specific WTO “Hilton” quotas, once the new FTA enters into force (combined this equates to around 46.8 Kt, which signifies a net increase of about 52.2 Kt, once the full TRQ has been phased in). The volume under the new FTA will be phased in in six equal annual stages.

- Poultry: 180 Kt CWE duty free, subdivided into 50% bone-in and 50% boneless. This will also be phased in via six equal annual stages. The 2024 updated negotiations also feature an additional 1.5 Kt of TRQ to Paraguay.

- Pigmeat: 25 Kt with an in-quota duty of €83 per tonne. The volume will be phased in in six equal annual stages.

- Sugar: elimination at entry into force of the in-quota rate on 180 Kt of the Brazil-specific WTO quota for sugar for refining. No additional volume other than a new quota of 10 Kt duty free at entry into force for Paraguay. Specialty sugars are excluded.

- Ethanol: 450 Kt of ethanol for chemical uses, duty-free. 200 Kt of ethanol for all uses (including fuel), with an in-quota rate 1/3 of MFN duty. Again, to be phased in in six equal annual stages. The 2024 updated negotiations also allow for an additional TRQ of 50 Kt of biodiesel to Paraguay on account of its land-locked and developing country status.

- Rice: 60 Kt duty free. This will again be phased in in six equal annual stages.

- Reciprocal tariff rate quotas: these will be opened by both sides and phased in over 10 years;

- Cheese: 30 Kt duty free. This will be phased in in ten equal annual stages stages. The in-quota duty will be reduced from the base rate to zero in ten equal annual cuts starting at entry into force.

- Milk powders: 10 Kt duty free. This will also be phased in in ten equal annual stages, with a similar reduction in in-quota duty as outlined for cheese.

- Infant formula: 5 Kt duty free. The will again be phased in via ten equal annual stages with similar reductions in in-quota duties as described above.

- Environmental safeguards: adherence to the Paris Agreement is included as an ‘essential element’ of the FTA. The agreement could be suspended if a party leaves the Paris accord or stops being a party in ‘good faith’ (i.e. undermines it from within). There are also additional provision around promoting sustainable supply-chains, helping to conserve biodiversity / livelihoods of indigenous peoples, especially in the Amazon.

There are concerns amongst several EU Member States, notably France, Ireland and Poland, about cheap imports from Mercosur undercutting EU products, compounded by less stringent production standards. A 2021 study by the Irish Government estimated that the EU-Mercosur deal could reduce the value of Ireland’s beef output by €44 – €55 million, equating to around 2-3% of output.

Whilst South American beef might not be permitted to come into the UK as a result of the EU-Mercosur FTA, there could be indirect impacts. For instance, displaced Irish beef will seek to find markets elsewhere with the UK being the most obvious choice. This could exert some downward pressure on UK beef prices, particularly in the food services segment. That said, UK beef prices have been very firm of late due to lower supply and in any case, it may take several years’ yet before an EU-Mercosur FTA enters into force, even if it gets that far. The likes of France and Ireland are likely to push back strongly against the deal.

Of course, if the EU can negotiate an FTA with Mercosur, the UK will also have an interest in exploring FTA opportunities, but that does not appear to be a priority for Labour presently. If/when negotiations do start, Mercosur is likely to seek more significant concessions with the UK, especially bearing in mind the precedent set by the Australia and New Zealand FTAs. However, it could be after the next UK General Election before a concrete trade deal is reached with the likes of Mercosur.

EU-NZ Trade Deal

On 9th July, the EU and New Zealand (NZ) reached an agreement on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). From an agricultural perspective its key provisions include:

- Elimination of all duties on EU agri-food exports to New Zealand: will be effective upon entry into force. This also includes wine, confectionary and dairy products including speciality cheeses.

- NZ access to the EU: greater access has been achieved for its agricultural exports to the EU, including for;

- Beef: a new tariff rate quota (TRQ) for 10,000 tonnes (t) with a reduced duty of 7.5%. This volume will be gradually phased in over 7 years from entry into force of the agreement.

- Sheepmeat: a new 38,000t TRQ to be imported duty-free. Again, this volume will be gradually phased in over 7 years.

- Milk powder: a 15,000t TRQ with a 20% import duty, to be phased in over 7 years.

- Butter: for the pre-existing TRQ of 41,177t which currently attracts a 38% import duty, for 21,000t of this TRQ, the duty will gradually be reduced to 5%. There will also be a new butter TRQ of 15,000t which will also see in-quota duty rates gradually fall to 5%. This means the NZ TRQ access will increase to 56,177t, with 36,000t of this seeing duties gradually fall to 5%.

- Cheese: a new TRQ of 25,000t to be imported duty-free. This will gradually be phased in over 7 years. NZ’s existing TRQs of 6,031t allocated under the EU’s WTO schedule will see tariffs eventually reduced to 0%.

- High-protein whey: new 3,500t TRQ to be phased in over 7 years at 0% duty.

- Other TRQs: for sweetcorn (800t) and ethanol (4,000t) will also be eventually at zero duty.

- Sustainability: both sides claim that the dedicated Chapter on Sustainable Food Systems and Animal Welfare makes significant advances on the provisions of most existing trade deals and that the parties will work together on animal welfare, food, pesticides and fertilisers.

- Geographic Indicators (GIs): the EU claims that 163 of its most renowned food GI’s will be protected in NZ as well as the full list of GIs for EU wines. GIs for 23 NZ wines will also be protected in the EU market.

The agreement will draw inevitable comparisons with the UK-NZ trade deal. Certainly, NZ’s access to the EU market is much more curtailed for beef, sheepmeat and dairy products in comparison to the relatively more generous access that the UK has granted. Therefore, the competitive pressures exerted on EU producers as a result of this deal will be much less pronounced. Over the longer term, for EU Member States such as Ireland, the UK-NZ trade deal could end up being more influential on its animal product sales as NZ exports to the UK could displace notable volumes of Irish beef exports to the UK.

Both the EU and NZ will now begin the ratification processes for this deal. Therefore, the entry into force of this FTA is still some time away.

Trade Deals Study

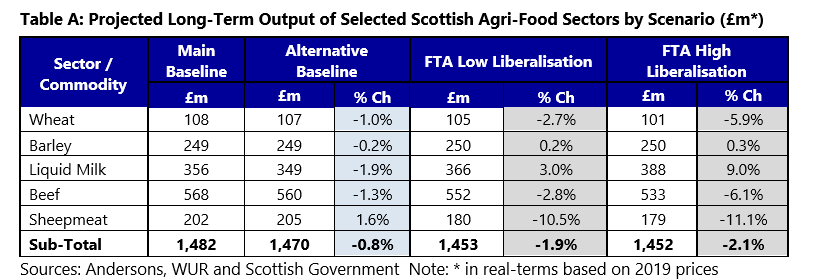

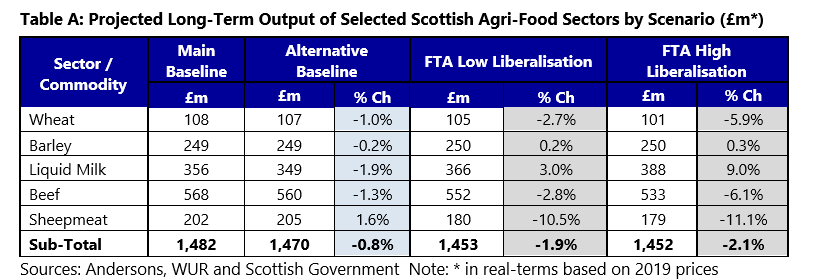

The Scottish Government has published a study on the impact on Scottish agriculture of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) between the UK and four selected non-EU partners, namely: Australia; New Zealand (NZ); Canada; and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). It found that these free-trade deals could have a significant negative impact on certain sectors of Scottish farming, particularly sheep. The study was undertaken, in 2022, by Andersons and Wageningen University and Research (WUR).

The study quantifies the FTA impacts on selected Scottish agricultural sectors namely: cereals (wheat and barley); livestock (dairy, beef, and sheep); and potatoes. This was done using two FTA scenarios; high and low liberalisation. These were modelled alongside the current status quo (UK has left the EU but the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is in place). An Alternative Baseline (No-Brexit) scenario was also briefly examined.

The research was undertaken in collaboration with Wageningen University and Research (WUR) and used a combination of MAGNET, a computable general equilibrium economic model to assess the individual and aggregated impacts of each FTA, as well as desk-based research and interviews with industry experts based in Scotland, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the Gulf region.

Key Results

- Impact of the selected FTAs is generally limited, but significant in some sectors: as Table A depicts, the projected long-term impact of the FTAs on Scottish output is relatively small in most cases. The exceptions are sheepmeat, where output is forecast to fall by around 10.5% to 11% under the Low and High Liberalisation scenarios. Beef and wheat are also projected to fall (both by around 3% to 6% depending on the scenario). Conversely, liquid milk output is forecast to grow by 3% to 9% in value terms, indicating significant FTA opportunities for dairy products. Barley is forecast to show a small long-term gain.

- Cumulative impacts of future FTAs will be more significant: although the aggregated impact of the selected FTAs is relatively limited, the cumulative effect of multiple trade deals over the longer term should not be underestimated. This is especially so if the UK agrees FTAs with agricultural powerhouses such as the US and Mercosur (including Brazil and Argentina).

- FTAs with Australia and NZ are main drivers of declines Scottish sheepmeat output: the new FTA is seen by many as a strong signal for NZ businesses to recapture trade with the UK, which was lost when the UK joined the EEC. Australia will also be keen to increase sheepmeat exports to the UK.

- Beef sector will come under pressure but some opportunities also exist: whilst imports from Australia and NZ will create more competition, a trade deal with Canada is likely to generate some export opportunities. Given the brand recognition of Scotch beef, it should be relatively well-positioned to exploit such niches. That said, safeguarding domestic sales, particularly to UK retailers, from overseas competitors will remain most crucial.

- The FTAs with Australia and NZ set important precedents: the recently agreed FTAs with Australia and NZ give important signals to other countries on what the UK is willing to cede in trade negotiations. Therefore, the standards that the UK is willing to accept for imports is pivotal, especially as other FTA partners will likely push for more concessions during negotiations. Any significant changes to standards relating to food safety and hygiene, the environment and animal welfare will have major implications for Scottish produce. This is not just on the home market, but overseas as well, especially in terms of highly-renowned brands such as Scotch Beef.

- FTA opportunities for dairying the dairy sector is best positioned to see export growth, particularly to the GCC, where Scottish dairy produce has already gained traction in high-end segments. UK exports to GCC in 2018-20 are valued at £38m and could rise by as much as 49% in a High Liberalisation scenario. Opportunities theoretically exist to export to Canada, but, as it is highly protectionist, sales are likely to be limited to select niches.

- Long-term impact of Brexit is deemed to be limited: Table A also shows relatively small differences in output under the Main Baseline (incorporating Brexit) and the Alternative Baseline (No-Brexit scenario). Although seed potatoes were not modelled, the loss of the EU markets for Scottish seed potato exports is significant and the restoration of this market access is a key goal for the sector. It should also be a primary objective for policy-makers.

- Significant Farm Business Income (FBI) declines: of up to 60% in some sectors, in both the Main Baseline and FTA Scenarios in comparison with the Base Year (2019/20) although the differences between the Main Baseline and FTA scenarios are quite small. This is chiefly linked with declining prices.

- New FTAs to have negligible impact on potatoes: industry input suggests that the new FTAs will have minimal impact on seed potatoes’ profitability. Instead, the impact of the loss of the EU market for Scottish seed potatoes is estimated to have led to a decline in seed potato prices of approximately 4%. Restoring market access to the EU27 and Northern Ireland is a priority for the sector.

Overall, the findings that more pressure will be exerted on the Scottish (and UK) beef and sheepmeat sectors are unsurprising as Australia and New Zealand are widely regarded as significant and highly competitive players on the world markets. That said, the projected extent of declines on output is perhaps not as pronounced as some might have feared, although the declines are still significant. The report also suggests some opportunities for dairy products, particularly in the Gulf region.

The Summary Report is available on the Scottish Government website via: https://www.gov.scot/publications/analysis-impact-future-uk-free-trade-agreement-scenarios-scotlands-agricultural-food-drink-sector/

Agreement Reached on UK Joining the CPTPP

On 31st March, the UK Government completed negotiations to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), following over 2 years of negotiations. Whilst the accession agreement was signed at a virtual meeting of Trade Ministers, the legal text of the agreement has yet to be published, and there will be a ratification process in the UK similar to that of other recent trade deals (e.g. Australia and New Zealand). The key points from an agricultural perspective are:

- General economic impact: the UK will be joining a trade bloc of 11 countries, accounting for about 7% of global GDP. The UK already has bilateral trade agreements in place (or pending ratification in the case of Australia and New Zealand) with nine of these members, the other two being Malaysia and Brunei. Therefore, the additional economic gain from joining the CPTPP will be limited at a national level, with the UK Government estimating that it will boost UK GDP by 0.08% in the next decade. From an agri-food perspective, the UK joining the CPTPP will not alter the level of access that Australian and New Zealand exporters will have to the UK market.

- Import tariff concessions:

- Palm oil: controversially, import duties on Malaysian palm oil (currently up to 12%) will be eliminated upon entry into force. Given the environmental concerns around deforestation associated with palm oil production in Malaysia, this will attract strong criticism. The UK and Malaysian Governments have attempted to address this by publishing a joint statement as part of the environment chapter of the agreement which sets out commitments to promote sustainable production and protecting forests. Palm oil may provide greater competition for domestically-grown oilseed rape.

- Sheepmeat: Australian and NZ exports to the UK will remain subject to the TRQs outlined in the UK’s bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with these countries. Duties on imports from other countries, which are minimal, will be eliminated from entry into force.

- Eggs: Australian eggs will remain subject to the UK’s Global Tariff. Duties on imports from other countries will be eliminated over a 10-year period, although imports from these countries are likely to remain minimal.

- Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) on Imports to the UK: the following new TRQs have been agreed

- Beef: a new duty-free TRQ of 13Kt will be phased in over 10 years and will start at 2.6Kt. It only be available to Canada, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Malaysia and Brunei. Importantly, any beef imports will have to meet UK Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) requirements. The Canadians sought UK acceptance of its standards (which permit hormone-treated beef), but the UK withstood this. Also, Australia and New Zealand will not get any further access to the UK market under the CPTPP.

- Pork: a 55Kt TRQ will be phased in over 10 years (starting at 10Kt). Again, this will be available to the same countries listed above. Vietnam and Singapore will also have access to this TRQ for an initial 3-5 year period before their duties are eliminated via a bilateral FTA with the UK. This TRQ could present some competitive threats from the likes of Canada and Mexico, although some commentators don’t believe that Canada will pose an immediate threat as it currently only utilises a small proportion of its potential TRQ under pre-existing agreements.

- Chicken: a TRQ of 10Kt will again be available to the countries listed above. A 10-year phase-in period will again apply. Vietnam and Singapore will again have access to this TRQ for an initial 3-5 year period before tariffs on imports from these countries are eliminated.

- Sugar: a 25Kt tonne TRQ will be shared by Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, Peru, and Vietnam. Canada will also have access to this TRQ for an initial two-year period before its tariffs will be eliminated as per the bilateral (roll-over) FTA that the UK has with Canada.

- Rice: for long-grain milled rice, there will be a 10Kt TRQ to be shared by Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, and Peru. Most-favoured nation (MFN) duties will continue for rice from Australia, Japan and Mexico.

- Other CPTPP countries: will have access to the UK market as agreed in existing (pending) bilateral trade deals. As our previous articles on the Australian and New Zealand trade deals have noted, bilateral TRQs of beef and lamb will be phased in over 15 years, whilst dairy TRQs will be phased in over 5 years.

- Tariffs and TRQs on UK Exports: as the UK was perceived to be quite defensive in the access that it is offering to importers, the market access for UK exports has also been limited to some key areas, including:

- Whisky: exports to Malaysia will see tariffs of up to 80% being reduced down to zero over a 10-year period which should help Scotch whisky to gain further market share. This is seen as a significant win for the UK.

- Dairy exports: the Canadian Government has not made any additional market openings available. This means that the UK will need to compete with other members for Canada’s CPTPP TRQs for dairy products (16.5 Kt). This is unsurprising given the UK’s stance on Canadian beef imports and the Canadian dairy sector is highly protected. There will be similar additional cheese TRQ of 6.5Kt on exports to Mexico, again, this will be shared with other CPTPP members. Similar arrangements to Canada will be put in place for to any UK dairy exports to Chile, Japan, Mexico, Peru and Vietnam.

- Beef: British exports of beef will be subject to a TRQ under the CPTPP. There is limited further detail at this stage and it will require the publication of legal texts to confirm what is available. In 2022, it is estimated that the UK exported 4.4Kt of beef to Canada and the CPTPP potentially presents an opportunity to grow this volume. Tariffs on UK beef exports to Mexico (up to 25%) will be eliminated after a staging period. There will also be staged liberalisation on exports to Peru, although export opportunities to Latin America will be limited.

- Pork and poultry: tariffs on UK exports to Mexico, of up to 25% and 75% respectively for pork and poultry, will be eliminated over a staging period. Similar provisions will apply to poultry meat exports to Peru and pork exports to Vietnam.

- Other goods’ exports: over 99% of UK goods’ exports will be eligible for tariff-free trade upon accession. For other goods where tariffs are being phased out, the UK has agreed to catch-up to other CPTPP members who are in Year 6 of their various multi-year tariff phase-out schedules. Importantly for the UK, this includes Malaysia agreeing to phase out its 30% tariff on car imports.

- Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures: as mentioned above, the UK has offered no concessions on this. However, the deal does provide a framework for more transparency and information sharing on SPS issues, which would help with addressing food fraud. The UK has also managed to formalise the principle of ‘regionalisation’ meaning that in the event of animal or plant disease outbreaks, trade restrictions would only be limited to affected regions.

- Other provisions: for goods, there will be multilateral cumulation which basically means that intermediate goods (e.g. car parts) from any country will count as ‘local’ for the purpose of accessing tariff concessions on trade within the bloc. So, UK car parts sold to a Vietnamese automotive plant would be classed as local for any Vietnamese car exports from that plant to Malaysia. In terms of services, UK companies will be able to operate in all CPTPP countries without the need to establish a local base in each territory. This will be a significant gain for the UK financial services sector in particular. The CPTPP chapter on the environment largely formalises commitments made by the UK and other CPTPP members under other international agreements.

Overall, whilst joining the CPTPP might help the UK to gain greater access to some Asia-Pacific markets (particularly Malaysia), its impact from an agricultural perspective looks set to be limited. As mentioned above, the UK already has bilateral trade deals with most members and most agricultural trade will continue to be conducted via these bilateral trade deals. In the longer term, a bigger issue could be what happens if the US joins the CPTPP, as it had agreed to join its predecessor (the Trans-Pacific Partnership), until the Trump administration pulled out. Although the current US administration is not overly focused on international trade, the prospect of a future US administration re-joining a Pacific trade bloc (CPTPP, or a subsequent deal) should not be ruled out. This would have much more significant implications for agriculture from both a market access and SPS perspective.

What happens next?

- The legal text of the agreement will be formalised and published in due course.

- From there, the agreement will come under Parliamentary scrutiny and this should include an examination and report by the Trade and Agriculture Commission; similar to the reports it compiled for the Australia and New Zealand trade deals. This will be done to verify that accession to the CPTPP is consistent with UK laws concerning animal welfare, food safety and environmental protection.

- Existing CPTPP members will also have their own ratification processes, which could potentially result in delays, although this is not anticipated as things stand.

- The UK is expected to be formally approved to join during a Ministerial meeting of CPTPP members during the summer, with the ratification process will then need to be completed by all CPTPP members.

Further information can be obtained via: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnershipcptpp-conclusion-of-negotiations/conclusion-of-negotiations-on-the-accession-of-the-united-kingdom-of-great-britain-and-northern-ireland-to-the-comprehensive-and-progressive-trans-pac

Trade Update

After a relatively quiet few months on the trade policy front, recent weeks have seen a resurrection of previous debates around the future long-term relationship that the UK should have with the EU as well as the impact of new trade deals that the UK is in the process of concluding.

Talk of a Swiss-Style Relationship

Following the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, rumours emerged from Government circles of a change in approach towards the long-term relationship that the UK would have with the EU. This would see it move towards something more akin to Swiss-style relationship. This would mean accepting free movement, contributions to the EU budget, dynamic alignment with EU regulations for goods, and European Court of Justice (ECJ) oversight in return for being part of the Single Market. Whilst some welcomed this, others claimed it was a betrayal of Brexit.

What many failed to acknowledge was that the EU is dissatisfied with how its relationship with Switzerland is structured as it requires more than 100 bilateral deals to replicate Single Market requirements and which constantly need to be renegotiated. It is unlikely to want to replicate this with the UK. In any event, the UK Government later denied that it was seeking to move to a Swiss-style relationship.

That said, and from an agri-food perspective, there is merit at looking at elements of the EU-Switzerland relationship and replicating aspects that make sense for both parties. In previous articles, we have advocated a Swiss-style Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) agreement with the EU, whereby the EU would permit frictionless access for UK agri-food goods in return for the UK dynamically aligning with EU regulations. Whilst previous Tory administrations (i.e. under PMs Johnson and Truss) dismissed this approach, it would appear that the Sunak administration is at least considering it.

Such an SPS agreement would greatly assist UK exports to the EU, its biggest trading partner and it would also overcome key hurdles in the ongoing NI Protocol negotiations, which have shown some tentative signs of progress recently. Whilst it would mean the UK mirroring EU laws, it would still leave scope, albeit more limited, for the UK to negotiate separate trade deals and trading arrangements, as the Swiss have done with the US. The UK could also give notice (e.g. of one year) if it wanted to discontinue this arrangement.

Overall, the talk of using existing templates in framing the future UK-EU relationship is becoming unhelpful. The sooner a bespoke UK-style relationship emerges the better. This could incorporate key aspects of other templates, but it will need to respect key EU principles, meaning that further negotiation is needed. It will also need to incorporate the closer relationship that NI will have with the EU, as it is de-facto part of the Single Market for goods by virtue of the NI Protocol.

Eustice Attack on Recent Trade Deals

On 14th November, during a House of Commons debate on the Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill, the former Defra Secretary George Eustice severely criticised the UK Government’s negotiating strategy for both trade deals. He singled out the then Trade Secretary, Liz Truss, for particular criticism, especially for imposing an arbitrary target of concluding negotiations with Australia ahead of the 2021 G7 summit. He thought that this severely weakened the UK’s bargaining power. Mr Eustice recalled that there were ‘deep arguments and differences in cabinet’, which were mirrored by friction between Defra and the Department for International Trade (DIT) during the negotiations. He also claimed that the ‘Australia trade deal is not actually a very good deal for the UK’ and that he tried his best when Defra Secretary to address its shortcomings. Specifically, he claimed that there was no need to give Australia (and New Zealand) unlimited access over the longer term for sensitive sectors such as beef and lamb.

From a farming perspective, it is all well and good to criticise the deal. But during his time in Government, Mr Eustice defended it – his comments, therefore, offer scant consolation to farmers who perceive these deals to be a significant threat. Both the Australian and New Zealand agreements will increase the competitive pressure on UK agriculture, particularly in grazing livestock. However, recent studies looking at the impact of these trade deals projected that the impact may be lower than some fear. That said, being the first new trade deals that the UK has negotiated from scratch since leaving the EU, they create an important precedent, and the cumulative impact of multiple trade deals can have a more significant impact.

The UK-Australia trade deal was ratified by the Australian Parliament on 22nd November. The Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill is making its way through Westminster. It is currently at the Report Stage, where amendments can still be made to the Bill, before a final third reading and subsequent vote on the Bill in the House of Commons – the date of which has yet to be announced. The House of Lords will also have to vote on the final Bill and they could delay it for up to a year before it would receive Royal Assent (assuming it is passed by the House of Commons).

Northern Ireland Protocol Bill

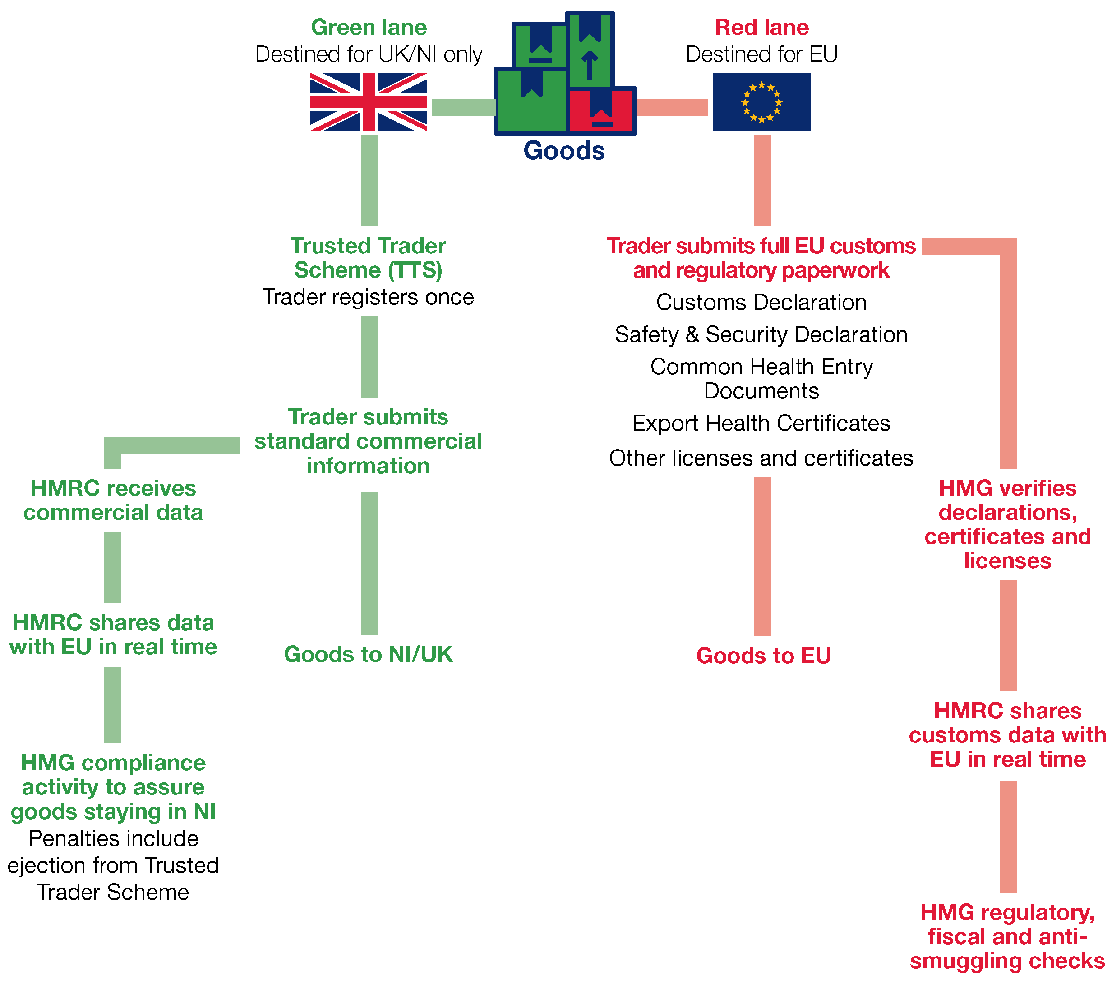

On 13th June, the UK Government introduced the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol Bill to the House of Commons. The highly controversial Bill, if enacted, would dis-apply large swathes of the NI Protocol which was agreed between the UK and the EU as part of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiations. The Bill’s legal text which is highly complex and potentially far-reaching drew harsh criticism from multiple sources. It has been met with particular disdain by the EU which sees the Bill as a breach of international law and the Commission is set to respond in the near future. At a top-level, the Bill seeks to do three things;

- Disapplies large parts of the Protocol: relating to most provisions that apply EU rules on the movement of goods into NI.

- UK’s Protocol alternative: is outlined and the UK Government provides some guidance on how it would be implemented.

- European Court of Justice oversight: the Bill would remove the Court’s direct jurisdiction and the role for EU institutions

In essence, the Bill is effectively rewriting the Protocol, in a unilateral manner, outside of the structures agreed by the UK Government and the EU. Whilst the political fall-out will continue to generate intense debate, it is the accompanying policy paper which provides practical insights on how the Bill would work and the implications for agri-food. The key points are;

- Establish new ‘green channel’ arrangements for goods staying in the UK: it is claimed that this would fix the burdens and bureaucracy caused by the application of EU Customs and SPS rules. This channel would only be available to firms registered as ‘trusted traders’ and this scheme would be overseen by UK Authorities. Goods moving on to the EU or moved by firms not in the trusted traders’ scheme would use the ‘red lane’ and be subject to the full range of regulatory checks. This would significantly reduce the sometimes complex certification requirements for agri-food produce. Here, the UK proposals are not that far from the EU proposals published last October which suggested an ‘Express Lane’ for goods moved by trusted traders which would be consumed in Northern Ireland.

- Establish a new ‘dual regulatory’ model: this is intended to provide flexibility for NI firms to choose between UK or EU rules on product standards. It is intended to remove barriers to trade within the UK internal market and the UK Government claims that it will encompass robust commitments to protect the EU Single Market. For agri-food, goods could only move from GB to NI under the trusted trader scheme (otherwise they would be in the red lane and subject to checks). There would be robust penalties for violations. The EU strongly objects to this proposal on the grounds that it undermines the integrity of its Single Market. There are also challenges around the bureaucratic complexities involved with dealing with two regulatory systems. Major NI agri-food businesses are also against these proposals as it would scare-off overseas customers from purchasing NI produce as they would be unsure on which standards the products are adhering to and would be deemed too complex and risky.

- State Aid and VAT: the UK Government states that the Protocol restricts the UK from providing the same tax and spend policies in NI as the rest of the UK—with little room for flexibility. This aspect of the Protocol was insisted upon by the EU so that there was a level playing field between NI and the EU Single Market and that NI firms, or GB firms with operations in NI, did not gain an unfair advantage. The new Bill gives the UK freedom to disapply these rules so that NI can have the same tax rules as other parts of the UK. Again, the EU strongly objects to these proposals.

- Role of European Court of Justice (CJEU): would be removed in dispute settlement and would provide the means for UK Authorities and Courts to set out the arrangements which apply in Northern Ireland. This is also highly controversial from an EU perspective as it would not have agreed the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the UK if the CJEU did not have ultimate oversight over the NI Protocol.

Whilst the full EU response is awaited, it has confirmed on 15th June it is restarting the legal proceedings it had initiated last year against the UK Government for its unilateral extension of grace periods for checks on products such as sausages and mince. These had been suspended for almost a year to facilitate negotiations on addressing the Protocol issues. The EU response is also likely to state that it reserves the right to enact much more stringent measures if this NI Protocol Bill becomes law in the UK. This would include suspending key aspects of the TCA or introducing some tariffs on UK exports to the EU. That said, the EU will also be keen to get the UK back to the negotiating table and the Commission has set-out further proposals on how it thinks the outstanding issues on the NI Protocol should be dealt with.

From an agri-food perspective, it is important to note that the House of Lords will vote against this Bill, thus delaying its enactment for at least a year. This gives time for further negotiations to take place. However, additional negotiating time has been wasted in the past. Breaching International Law (which legal experts almost entirely agree would happen if this Bill were to be enacted)) is not the way to build trust. What is needed now is quiet and determined diplomacy to reach a deal that all parties can live with.

NI agri-food businesses are adamant that the Protocol delivers major benefits in enabling NI to access the EU Single Market whilst having unfettered access to GB. As we have mentioned previously, a UK-EU veterinary agreement would help greatly to reduce the burden of checks, not just GB to NI but also GB to the EU. On this, the EU needs to be more flexible. The UK will not opt for a Swiss-style veterinary agreement as that would mean following EU rules for the whole of the UK. A bespoke veterinary agreement should be a key part of the framework to resolve the remaining Protocol issues.

UK/Australia FTA Analysis

On 13th April, the Trade and Agriculture Commission (TAC) published its advice to the International Trade Secretary (Anne-Marie Trevelyan) on the UK-Australia Free Trade Agreement (FTA). This is the first such piece of advice that the TAC has compiled and its findings have been presented to Parliament to aid its discussions on ratifying the trade deal.

The Terms of Reference for this TAC report focused on assessing whether, in relation to agricultural products, the new FTA is consistent with the maintenance of UK levels of statutory protection in relation to three key areas;

- Animal or plant life or health,

- Animal welfare, and

- Environmental protections

The TAC report addressed three questions which are set-out below, with the TAC’s conclusions on each question summarised in italics.

- Whether the FTA requires the UK to change its levels of statutory protection in relation to the three areas above? The TAC has found that the FTA does not require the UK to change its existing levels of statutory protection in relation to animal or plant life or health, animal welfare, and environmental protection.

- Whether the FTA reinforces the UK’s levels of statutory protection in these areas? The TAC’s view is that the FTA reinforces the UK’s statutory protections in the areas covered. It cites two reasons. First, the FTA contains environmental and animal welfare obligations that require the UK to maintain its statutory protections in the areas covered. Second, these obligations also ensure that Australia will not gain a trade advantage by lowering its standards of protection or not properly implementing its domestic laws in the areas covered.

- Whether the FTA otherwise affects the ability of the UK to adopt statutory protections in these areas? The FTA does not otherwise affect the UK’s ability to adopt statutory protections in the areas covered. It does not restrict the UK’s WTO rights to regulate in these areas, and potentially enhances these rights in some respects. However, the UK is able to adopt decisions under the agreement, together with Australia, that may constrain its freedom to regulate in future. Therefore, the TAC believes that it is important to ensure that the UK’s import control systems are properly resourced to manage increased imports under the FTA.

The TAC report also examines a number of other issues which have caused concern. These include;

- Pesticides: the TAC finds that the FTA is likely to lead to increased imports of products from Australia using pesticides which are banned in the UK. Whilst there are Commonwealth laws concerning the environment and pesticides use which Australia has obligations under, these laws are limited.

- GMOs: although there is negligible GMO production in the UK, it is currently legal to import and market GMO products, provided that it is labelled as such. The TAC suggests that it is possible that GM canola oil (from oilseed rape) from Australia could be imported in increased quantities under the FTA. However, imports of cotton and safflower, the other two major Australian GMO crops, will not be imported in increased quantities. Furthermore, the UK’s WTO rights to regulate the import of GM products remain the same under the FTA.

- Hormone-fed beef: the importation of such products would remain illegal in the UK and the FTA does not change this legal position.

- Feedlot beef: would inevitably increase under the FTA and it would be difficult under WTO law for the UK to impose restrictions.

- Hot branding: whilst legal in Australia, the UK requires electronic identification of cattle for export to UK, thus hot branding is unnecessary.

- Slaughterhouse CCTV and stunning: CCTV is not required in Australia and meat from these premises could not be restricted from being imported into the UK. The TAC also state that it is illegal to export meat from non-stunned animals so such meat should not enter the UK as a result of the FTA.

- Mulesing: is the practice of removing wool-bearing skin, without pain relief, from the buttocks of a live animal and is done by Australian sheep farmers to prevent flystrike. The TAC found that the likelihood of mutton from mulesed sheep being imported into the UK is negligible but there is a “much higher chance” of wool from mulesed sheep being imported.

Overall, whilst the TAC has found that whilst imports using the most controversial practices (e.g. hormone-fed beef) will continue to be prohibited, there is scope for increased competition from Australian imports, particularly beef, lamb and wheat, which sometimes will be produced to lower animal welfare and environmental standards. However, it is worth acknowledging that Australian beef and lamb is currently achieving high prices in the global market (particularly Asia), thus making exports to the UK somewhat less attractive, at least in the short-term. Of course, in the long-term, supply/demand and geopolitical influences can change the market situation significantly. Importantly, the UK-Australia FTA creates a precedent for other trade deals. Whilst this FTA alone does not alter the playing-field that significantly, the cumulative impact of trade deals will have a much more influential impact.

For full detail on the TAC’s advice, please visit: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1068872/trade-and-agriculture-commission-advice-to-the-secretary-of-state-for-international-trade-on-the-uk-australia-free-trade-agreement.pdf

Also, please note that the TAC has launched a similar consultation on the UK-New Zealand trade deal. More detail via: