On 17 May, the Foreign Secretary, Liz Truss, made a statement in the House of Commons on the Government’s intention to introduce legislation to make changes to the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol. During her statement, the Foreign Secretary stated that her preference remains a negotiated solution with the EU. To this end, she invited European Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič to a meeting of the Withdrawal Agreement Joint Committee. However, she also said that various aspects of the Protocol are not working. She stated that the new Bill would address these issues whilst claiming it would also uphold the provisions of the Good Friday Agreement and be consistent with international law – points that the EU, in particular, disagrees with.

The new Bill, due to come before Parliament in the coming weeks would focus on addressing issues around;

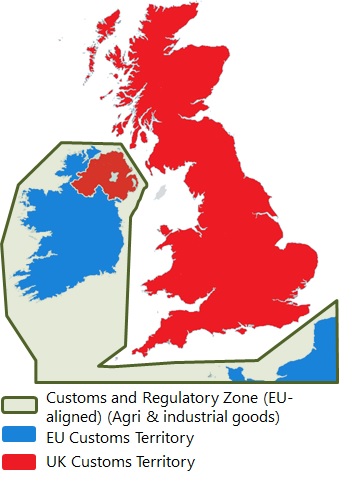

- The movement of goods: particularly relevant to agri-food, where the Protocol is not yet fully functional in some areas as a result of the grace periods already put in place by the UK Government for products such as sausages and mince

- Goods regulation: also of relevance to agri-food, and concerns NI having to follow EU rules for goods which has precedence in NI over rules that the UK might introduce in the future (which could diverge from the EU)

- VAT: NI remains within the EU’s regulatory orbit for VAT on goods

- Subsidy control: the EU’s State Aid rules are applicable to NI and, in some instances, British based companies that do business in NI.

- Governance: this links with the oversight that the European Court of Justice has over the NI Protocol.

The Foreign Secretary stated that the Bill would include a Trusted Trader scheme, effectively a ‘green channel’ for goods imported from GB and staying in Northern Ireland. It would also encompass the provision of real-time data to the EU with the intent of giving them confidence that goods intended for NI do not enter the EU Single Market, via the Republic of Ireland.

A dual regulatory regime is also suggested so that NI could follow UK rules for goods that would stay in Northern Ireland. Effectively, businesses would choose between producing goods to UK or to EU standards in Northern Ireland. Liz Truss also stated that robust penalties would be imposed for those seeking to abuse the proposed new system and promised further detail in the coming weeks.

Unilaterally disapplying key parts of the NI Protocol via UK legislation has the potential to place the whole post-Brexit trading arrangements between the UK and the EU in jeopardy. Whilst the EU has been somewhat muted in its response, Maroš Šefčovič clearly stated that the EU would respond ‘with all measures at its disposal’ should the UK follow through and enact legislation to override the NI Protocol. However, we remain several steps away from retaliatory action being taken.

If a Bill is brought before Parliament in the coming weeks, it needs to go through Parliamentary approval process. Most believe that the House of Lords would almost certainly vote against the Bill. This would mean a delay by one year to the Bill’s enactment. Some suggest that 20th June 2023 to be a potential key date, if the Bill gets to the final House of Lords vote by 20th June this year.

This gives some time for the UK and the EU to reach a negotiated solution. For agri-food businesses, it is unlikely that much will change in the interim.

There is a delicate balancing act required between the UK seeking to rewrite large chunks of the Protocol on the one hand and the EU Commission not having the mandate from EU Member States to renegotiate the Protocol on the other. That said, there is the scope for all parties to improve the Protocol and this must be the focus.

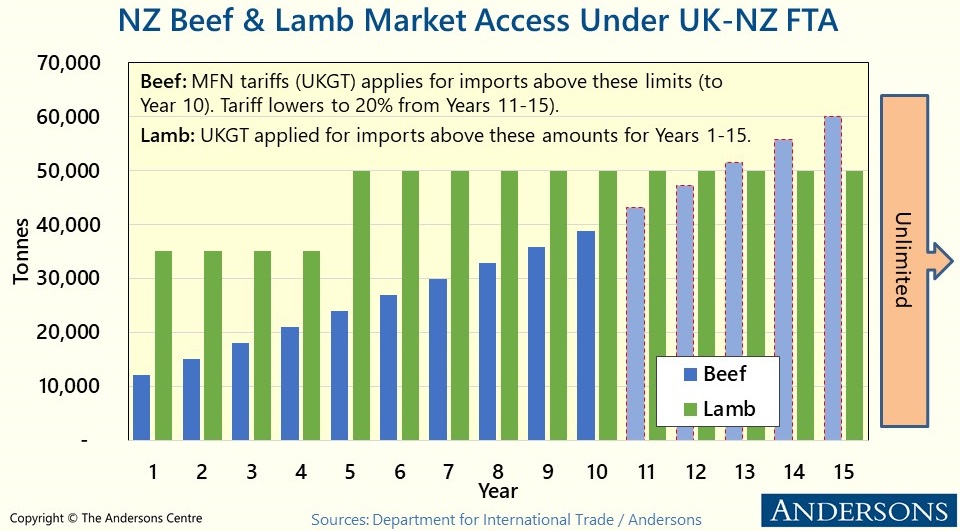

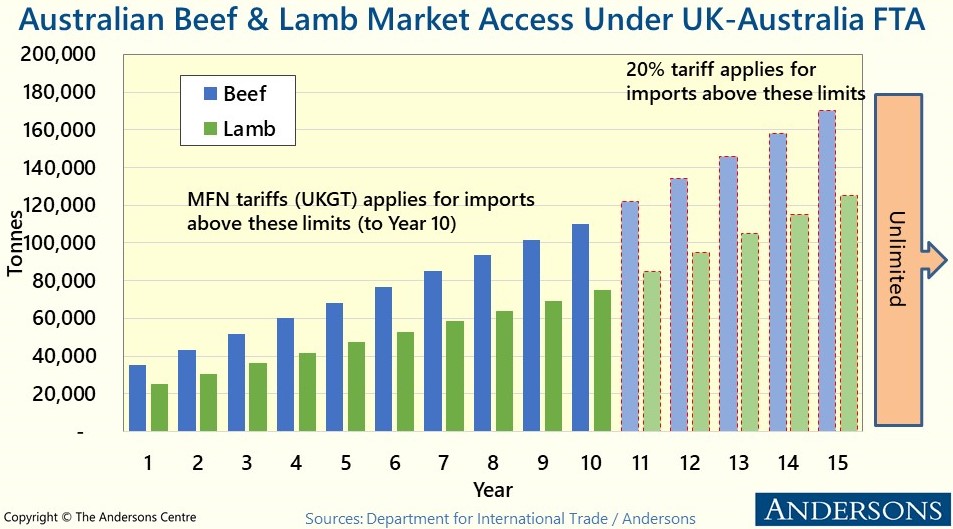

As we have stated in the past, a veterinary agreement between the UK and the EU would go a long way towards addressing the most problematic Protocol issues around the movement of agri-food goods between Britain and NI. This could be along the lines of the veterinary agreements that New Zealand has with the UK and the EU. This would still give the UK the ability to negotiate free trade deals with third countries. It would mean that some checks would remain, but at greatly reduced levels (e.g., 1% physical checks versus the default 15% for red meat). The DUP NI Agriculture Minister, Edwin Poots, has suggested a similar concept in the past.

It is most likely that a way will, eventually, be found to muddle through the current issues as this is what has occurred with the Brexit process to date. We are probably into the territory of having Protocol 2.0, 3.0 etc. in the coming years. This will most likely align, to some degree, with the vote that the NI Assembly will have on the Protocol every 4 years. In some ways, this would be akin to new versions of MS Windows that Microsoft brings to the market periodically – each new version is fundamentally the same operating system (Protocol) but with scope for improvements, even if certain aspects remain imperfect to some.

Further detail on the Foreign Secretary’s Statement to the House of Commons is available via: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/northern-ireland-protocol-foreign-secretarys-statement-17-may-2022