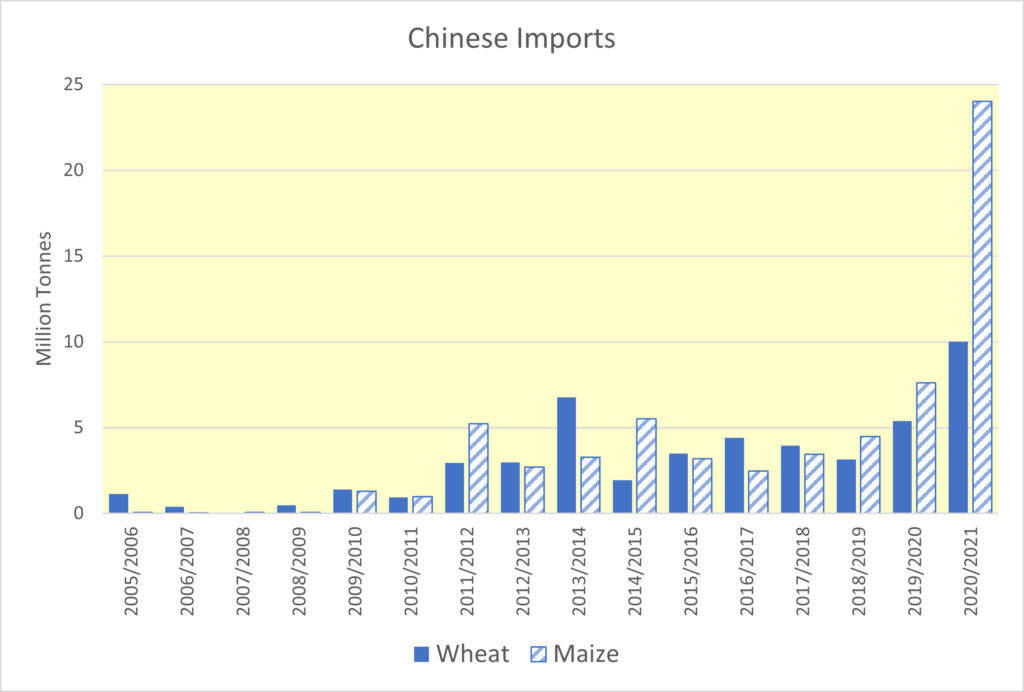

The world grain and oilseed markets remain dominated by a seemingly insatiable appetite by China to import ever-increasing tonnages of all grains and other commodities. It has been importing most of the world’s traded soybeans for many years now but has only recently entered the market for colossal amounts of maize and wheat too. This demonstrates that the Chinese agricultural policy of hundreds of years of being self-sufficient in grains is well and truly finished. According to statistics published monthly by the USDA, the Chinese now hold not only two thirds of global maize stocks (9-months’ Chinese demand), but also 50% of global wheat stocks, 35% of soybeans 60% of rice stocks and 40% of the cotton. Something is going on. Some global food supply reports suggest China is about to experience a major food shortage and global food prices are therefore likely to rise any time soon. Other reports suggest the stock levels are quite wrong and China is not hoarding quite so much. The truth is likely to be that even the USDA does not really know for sure what China has (perhaps the Chinese cannot be so sure), and of course, being part of the US Government, the USDA could have another agenda, but it’s the best information we have. China did build up similar stock levels at the turn of the Millennium, so it is not unprecedented. It subsequently then ran down stocks, contributing to a bearish grain market for some years.

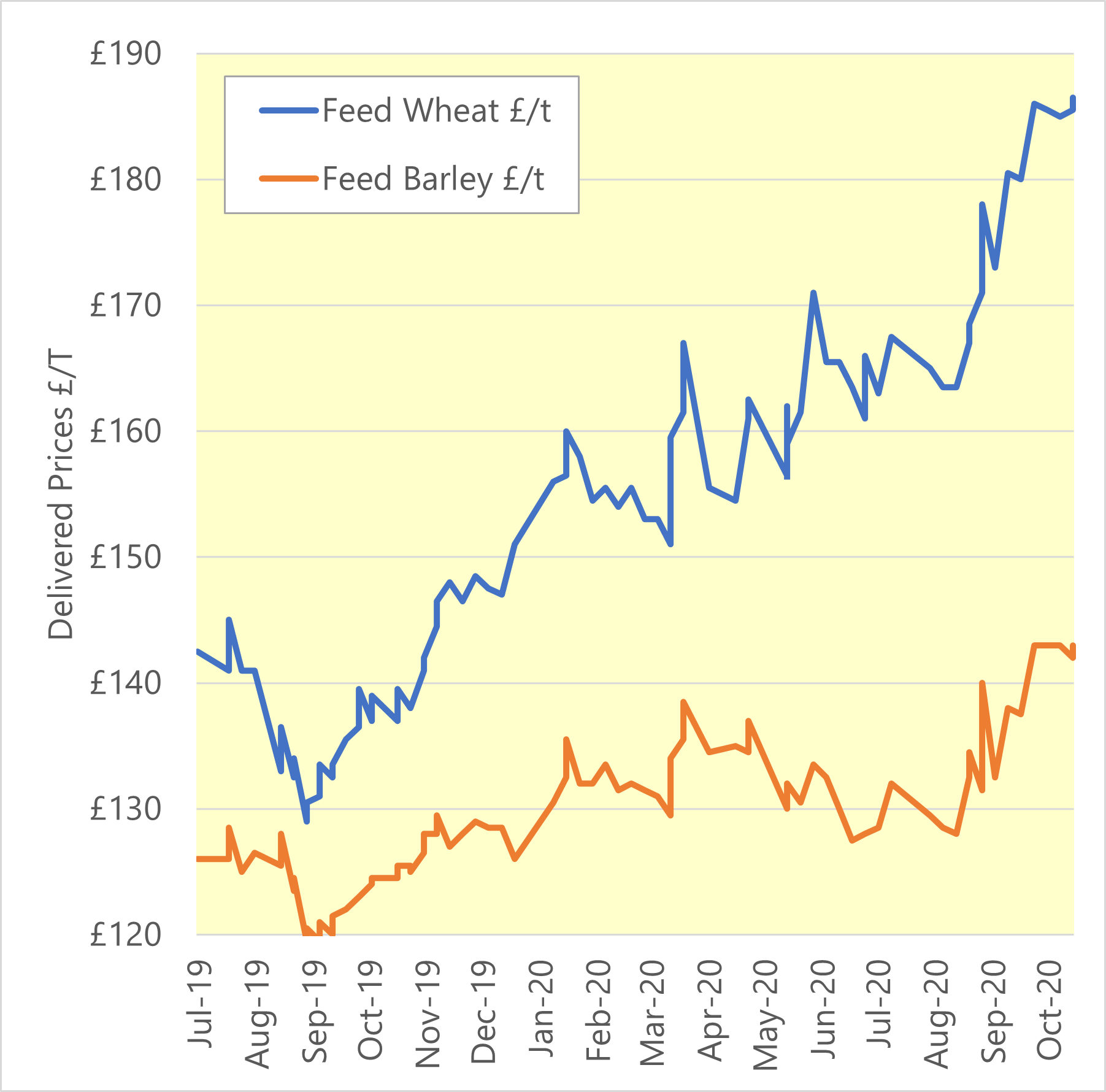

This time of year, crop reports from around the world are a major factor in the pricing of the new crop. People might look first at the eye-catching old crop prices, but as most of that will be sold by now (or at least committed and priced), the new crop is of more significance. November 2021 futures closed on the 25th March at £33 per tonne lower than May 2021, at £166 per tonne. Russian analysts have recently reported good growing conditions for their wheat and increased their tonnage projection by 3 million tonnes (to 79 million) despite relatively poor crop ratings. The Ukrainians too have done the same, reporting their wheat is in an excellent state and the positive reports travel through Europe too with Strategie Grains also posting good yield expectations for European wheat crops. Despite the avid export of all grains to China, it is these positive prospects for production that has taken the edge off the grain prices in the last month.

New crop barley, whilst still having a larger discount to feed wheat than most years, has at least fallen to £15-£20 per tonne from feed wheat which compares favourably against the £30+ discount for old crop. Not only is the production far lower than last year, but also we can hope that come June, people might start drinking more beer again so the malting industry might be rekindled.

The oat market took a boost this month with news that a new oat buyer is planning to set up in Peterborough. Oatly, a Swedish company will make milk from oats to supply the growing market for animal-milk alternatives (see below). Farmers have found oats a very useful crop agronomically in recent years, but held back from growing it as few buyers have been in the market, so perhaps this will encourage a greater cropped area.

Oilseed rape for post-harvest looks as encouraging as this season’s prices have proven to be. Perhaps some growers who opted away from the crop will be looking at these bid prices wishing they had tried growing it again. Perhaps next season, the crop will experience a resurgence of area cropped. The supply and demand table continues to look tight for new crop because, despite a likely rise in production from Canada, the largest producer, the other main regions (particularly Ukraine and Australia) look set to be lower. Europe will remain in deficit too with large planted area reductions throughout the continent.

Demand for pulses has fallen away this month, as is often the case in March, as the Australian crop starts reaching the North African buyers. The market will be thin from now on, and occasionally closed.