At one stage, there were thirteen candidates seeking to become the next Prime Minister (and leader of the Conservative party) and, in some ways, the leadership race was akin to the Grand National with a varied range of runners and riders, some of whom had little chance of success. In recent weeks, this has been whittled down to two candidates – Boris Johnson (previously mayor of London and Foreign Secretary) and Jeremy Hunt (Foreign Secretary). This article examines the credentials of both, particularly from an agri-food perspective.

Boris Johnson

Whilst being the front-runner from the outset, the former mayor of London does not have much form when it comes to agri-food matters. One of his few utterances related to complaints about the burden of EU regulations (e.g. on sheep disease) to protect consumers in advance of the referendum. He also promised farmers that their subsidies would be preserved post-Brexit.

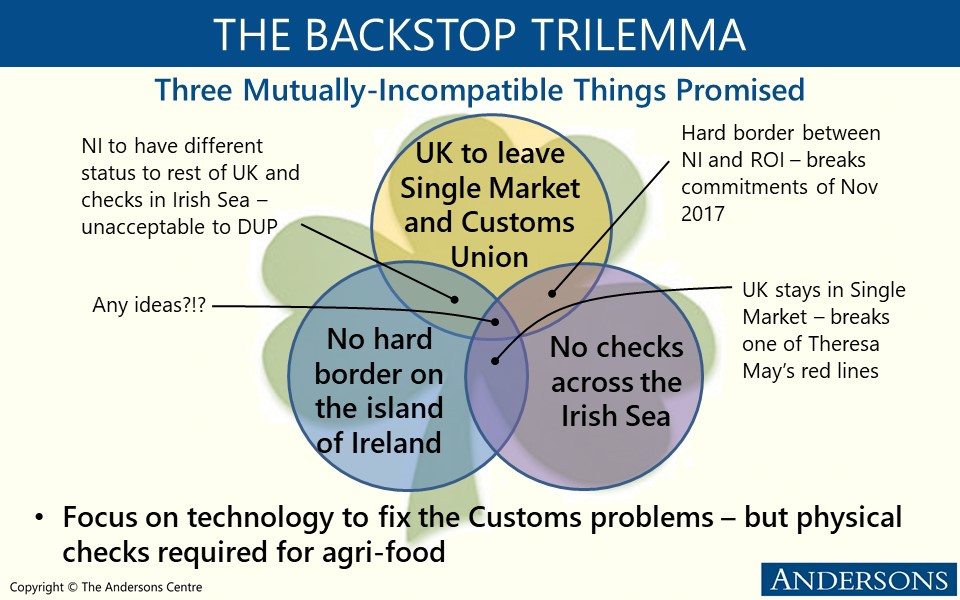

With regards to trade, at a January 2019 conference in Dublin, he was keen to emphasise that the UK still wants to do business with Ireland, noting to the audience that “we buy 78,000t of your cheese every year,” whilst also emphasising that he does not want to see a hard border in Ireland and that other solutions can be found. Although Mr. Johnson’s preference is for the UK to leave the EU with a deal, he is of the view that it is possible to leave the EU on 31st October without a Deal, claiming that it would be possible to extend existing arrangements for as long as necessary to negotiate a free-trade agreement under GATT: Article XXIV (24). Most trade policy experts dispute this claim, noting firstly that the application of this Article would require the EU’s agreement (highly unlikely in the event of a No Deal). In addition, according to paragraph 5, sub-paragraph (c) of Article XXIV, it could only be applied if there was a “plan and schedule” for the formation of a free-trade area or customs union with the EU “within a reasonable length of time.” By definition, none of this would be in place if there were to be No Deal on 31st October. Thus leaving the UK Government in the same conundrum as that faced by the May administration.

Jeremy Hunt

Jeremy Hunt does not have much of a track-record with regards to agriculture either. Before going into politics, Mr Hunt was an entrepreneur in technology marketing consultancy and in online publishing. In Government, he has held roles as Health Secretary and Foreign Secretary. Whilst not having much direct involvement in food and farming, he was the driving force behind a plan to halve childhood obesity by 2030 which he sees as a major cost burden to the NHS. Although his website devotes some attention to the Agriculture Bill, post-Brexit environmental protections, and policy, as well as food safety and food labelling, it is very much a reiteration of the current Government line on these issues.

Whilst siding with Remain in the June 2016 referendum, Mr Hunt was quick to row-in behind the effort to leave the EU by securing a deal which would enable the UK to continue to trade closely with the EU whilst emphasising the Government’s commitments to guarantee workers’ rights, consumer protection and environmental protection. He has mentioned that if there was no possibility of a Deal with the EU on 31st October that he would leave without a Deal if necessary. However, he is also open to a short extension if a Deal is within sight.

Although Mr Hunt claims to have a good rapport with EU leaders such as Merkel and Macron, he did attract the ire of Donald Tusk in October 2018 for comparing the EU with the Soviet Union. However, Mr Hunt’s track-record for controversy is much less than that of Mr Johnson and he is also seen as much less of a charismatic figure. Based on the voting to date, it appears to be an uphill task for Mr Hunt to become the next Prime Minister. His main hope might be for Boris Johnson to discredit himself with a major gaffe during the head-to-head contest over the next few weeks. He may also need to create a “stop Boris” alliance within the party, potentially giving key roles to the likes of Michael Gove, Sajid Javid, Rory Stewart and Amber Rudd in a bid to appeal to all sections of the Conservative party to re-unite after the ructions of Brexit. That said, it looks most likely that it will be Boris as PM after 22nd July. Whilst the Brexit journey has been eventful thus far, it looks set to go into overdrive in the Autumn.

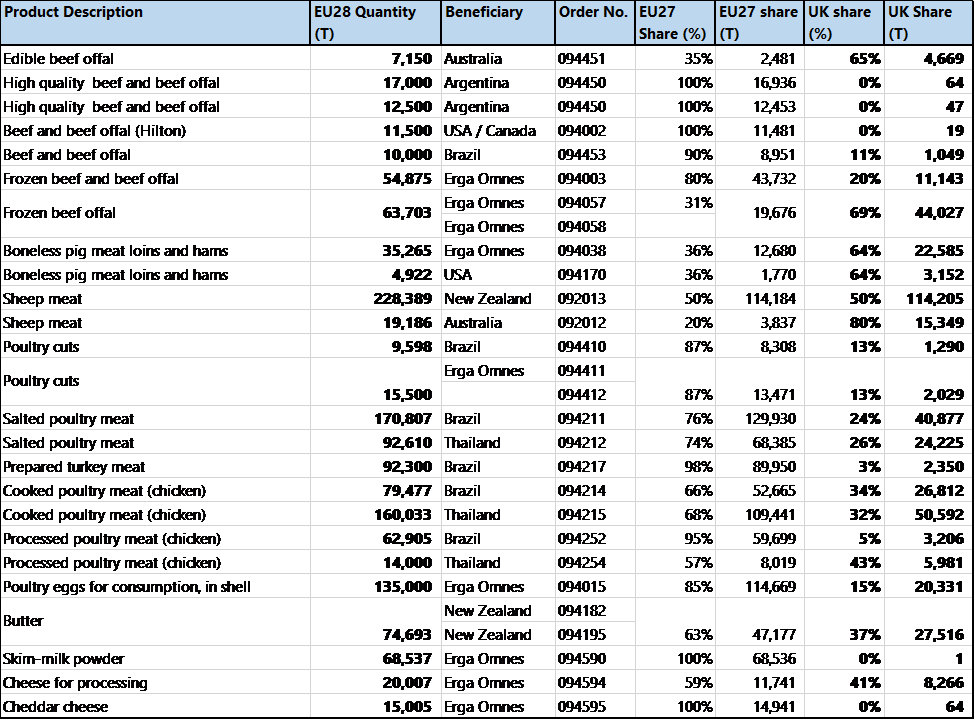

For the farming sector, it is a case of wait-and-see what might happen. Although Mr Gove is now out of the running to be PM, the possibility of a new Defra Secretary after a cabinet reshuffle has heightened. A Hunt administration is likely to mean more of the same in terms of the direction of agricultural policy. As for a Boris-led administration, who knows? Whilst farming might be lower down his policy agenda, trade is likely to be centre-stage and this could have significant long-term implications for the competitiveness of UK agri-food.