The negotiations on a post-Brexit trade deal have been thrown into disarray as the UK has threatened to unilaterally override parts of the Withdrawal Treaty. Boris Johnson’s Government proposes to use the Internal Market Bill currently progressing through Parliament to amend the implementation of the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol. This is despite the fact that the Treaty and Protocol were agreed by the Government less than a year ago, and that breaking Treaty obligations contravenes international law.

The EU was quick to react and told the UK that it must withdraw the relevant parts of the legislation before the end of the month. The UK has, so far, declined to do this. However, talks on a future Free Trade Agreement (FTA) will continue for now, although relations between the two sides have reached an all-time low.

The crisis began when the UK Government published its draft legislation on the UK Internal Market (UKIM) on the 9thg September. This was subject to a consultation during July and August (click here for article summarising the Government’s initial proposals). Whilst the draft legislation mainly deals with the functioning of the UKIM in a post-Brexit world, various elements impact on the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The UK Government claims that this is largely an exercise in ‘clarification’ although a Minister had to admit in Parliament that the proposals were in breach of the Withdrawal Treaty obligations. A senior UK Government legal adviser has resigned over the plans.

The UKIM legislation affects the NI Protocol in three main ways:

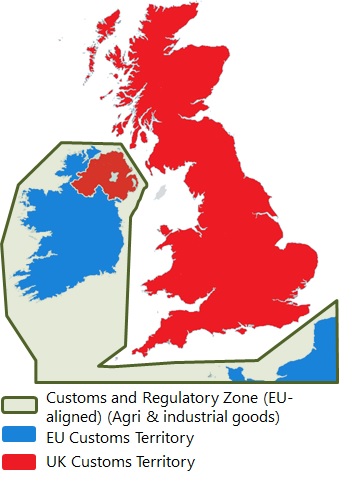

- Access from GB to NI: goods from GB entering into NI have to abide by EU standards based on the provisions of the Protocol. The UKIM legislation is not proposing to ignore that, however, in implementing the Protocol the UKIM legislation states that UK authorities have to show special regard for, and strengthen the integrity of the UK internal market. As things stand, this is not a controversial proposal and it is understandable that the UK would seek to uphold the integrity of its internal market. That said, it will be interesting to see how the UK defines goods that are ‘at risk’ of entering into the EU Single Market, which may be ineligible to do so if they are not covered by a Free Trade Deal or do not have the appropriate tariffs applied in a No Deal scenario. This is especially relevant for agri-food products and more detail on this is anticipated in the Finance Bill due to come before Parliament later in the year.

- Trade from NI to GB: here, the promise by the UK Government to give “unfettered access” for NI businesses to the GB market comes into play. The UKIM draft legislation gives the NI Secretary of State the powers to modify or disapply sections of the NI Protocol that requires NI businesses to complete additional EU paperwork (e.g. export summary declarations) for goods sold to the GB market. These intentions are causing concerns in EU circles as they are at odds with what the EU has understood to have been agreed under the Withdrawal Agreement. Exactly how the completion of this additional EU paperwork would operate in practice has still to be defined. Much of the information required will already be contained in commercial documentation. So, it should be possible to address this issue with information the NI businesses already compile, particularly as there is a Trader Support Service also available to NI businesses.

- State Aid Rules: this is perhaps the most controversial aspect as it continues to be a sticking point in the future relationship negotiations. Article 10 of the NI Protocol specifies that EU State Aid Rules apply to all trade relating to the Protocol. This includes GB companies with bases in NI and means that EU State Aid Rules reach into GB which the UK Government objects to. The UKIM legislation would again give powers to the NI Secretary of State to modify or disapply these powers, despite the UK Government’s own admission that these powers would contravene international law, as the Withdrawal Agreement is now legally binding. This has caused the most alarm on the EU side and the negotiations are very much at a make-or-break point.

Moving away from the Brexit-related aspects of UKIM, this legislation will be important for agri-food businesses operating throughout the UK. Goods produced in one part of the UK (e.g. Scotland) and meeting the required standards will be mutually recognised when placed on the market in another part of the UK (e.g. England). That said, if products produced in England are subject to lower standards than those applying in Scotland, the non-discrimination principle would mean that these products cannot be prevented from being offered on sale in Scotland. Accordingly, this gives the potential for products produced to a lower standard to be supplied across the UK and this has drawn sharp criticism from the devolved administrations as they believe it undermines any powers which might be repatriated to them (from Brussels) as a result of Brexit.

The draft UKIM legislation is accessible via: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0177/20177.pdf

The introduction of the UKIM was always going to be controversial but recent statements in Parliament by the NI Secretary of State has raised tensions to a new level, particularly concerning UKIM’s incompatibility with international law and its implications for the UK-EU negotiations. Given how controversial the Brexit negotiations have been, it was always likely that a flashpoint such as this would emerge, especially as we are reaching the climax of the talks. The prospects of a No Deal Brexit have increased. That said, the controversial points can still be ironed out in the remaining negotiations – if there is the will on both sides to achieve this. Also, it is worth pointing out that the UKIM legislation is likely to be modified significantly as it passes through Parliament and the House of Lords could potentially delay its passing by a year as it will have grave concerns about its current incompatibility with international law. What is clear is that even if an agreement is reached between the UK and the EU, significantly more time will be needed to implement any agreement. Whilst the Transition Period might end on 31st of December, a further Implementation Period is now necessary, such periods are common in other Free Trade Agreements.