After a relatively quiet few months on the trade policy front, recent weeks have seen a resurrection of previous debates around the future long-term relationship that the UK should have with the EU as well as the impact of new trade deals that the UK is in the process of concluding.

Talk of a Swiss-Style Relationship

Following the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, rumours emerged from Government circles of a change in approach towards the long-term relationship that the UK would have with the EU. This would see it move towards something more akin to Swiss-style relationship. This would mean accepting free movement, contributions to the EU budget, dynamic alignment with EU regulations for goods, and European Court of Justice (ECJ) oversight in return for being part of the Single Market. Whilst some welcomed this, others claimed it was a betrayal of Brexit.

What many failed to acknowledge was that the EU is dissatisfied with how its relationship with Switzerland is structured as it requires more than 100 bilateral deals to replicate Single Market requirements and which constantly need to be renegotiated. It is unlikely to want to replicate this with the UK. In any event, the UK Government later denied that it was seeking to move to a Swiss-style relationship.

That said, and from an agri-food perspective, there is merit at looking at elements of the EU-Switzerland relationship and replicating aspects that make sense for both parties. In previous articles, we have advocated a Swiss-style Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) agreement with the EU, whereby the EU would permit frictionless access for UK agri-food goods in return for the UK dynamically aligning with EU regulations. Whilst previous Tory administrations (i.e. under PMs Johnson and Truss) dismissed this approach, it would appear that the Sunak administration is at least considering it.

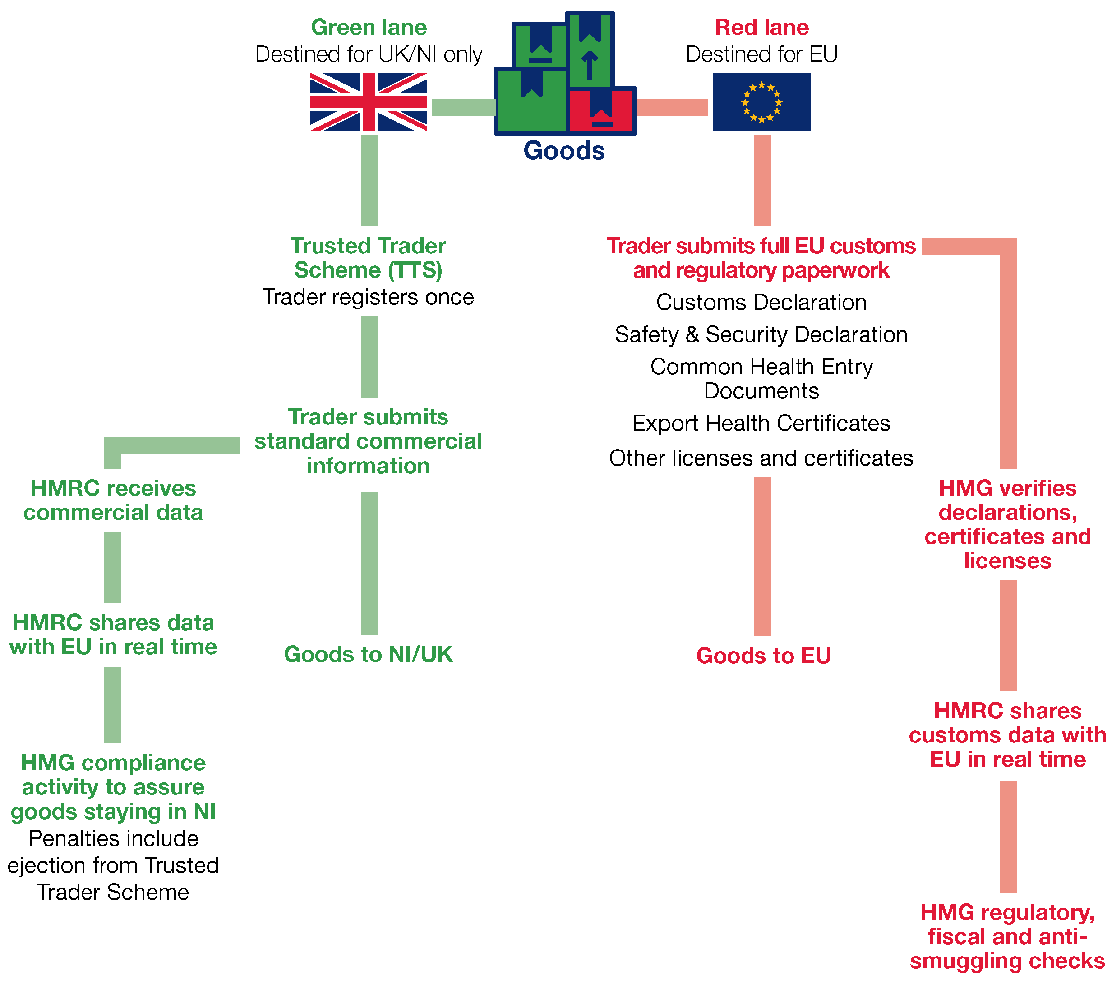

Such an SPS agreement would greatly assist UK exports to the EU, its biggest trading partner and it would also overcome key hurdles in the ongoing NI Protocol negotiations, which have shown some tentative signs of progress recently. Whilst it would mean the UK mirroring EU laws, it would still leave scope, albeit more limited, for the UK to negotiate separate trade deals and trading arrangements, as the Swiss have done with the US. The UK could also give notice (e.g. of one year) if it wanted to discontinue this arrangement.

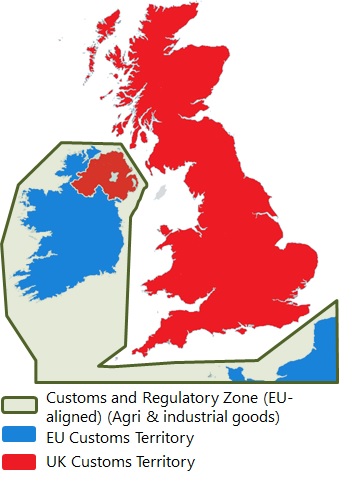

Overall, the talk of using existing templates in framing the future UK-EU relationship is becoming unhelpful. The sooner a bespoke UK-style relationship emerges the better. This could incorporate key aspects of other templates, but it will need to respect key EU principles, meaning that further negotiation is needed. It will also need to incorporate the closer relationship that NI will have with the EU, as it is de-facto part of the Single Market for goods by virtue of the NI Protocol.

Eustice Attack on Recent Trade Deals

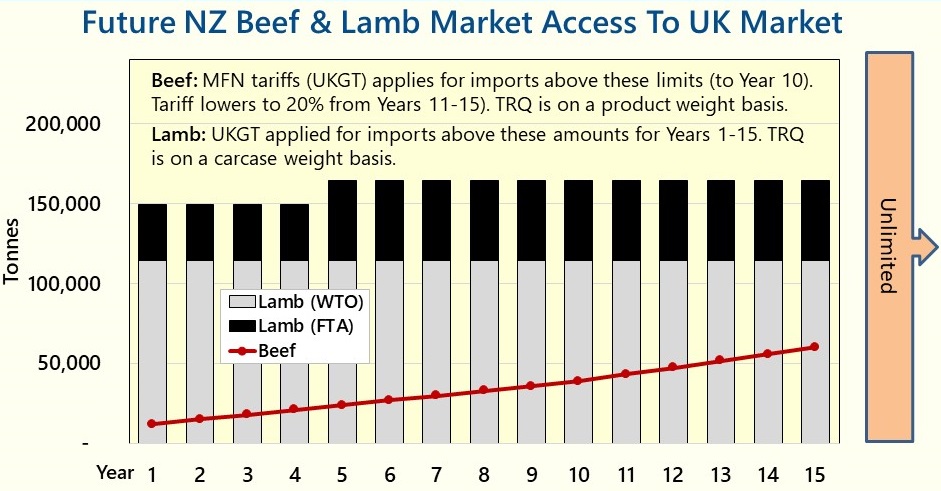

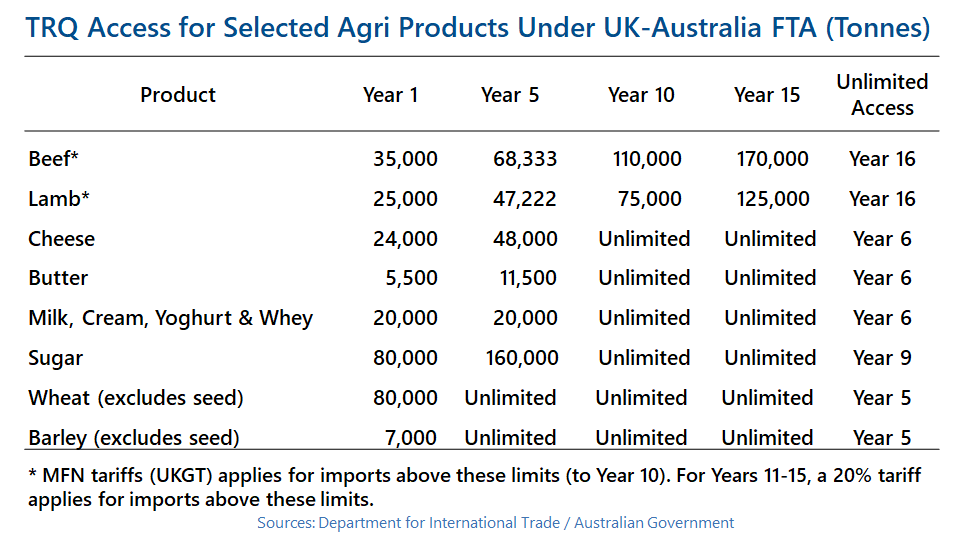

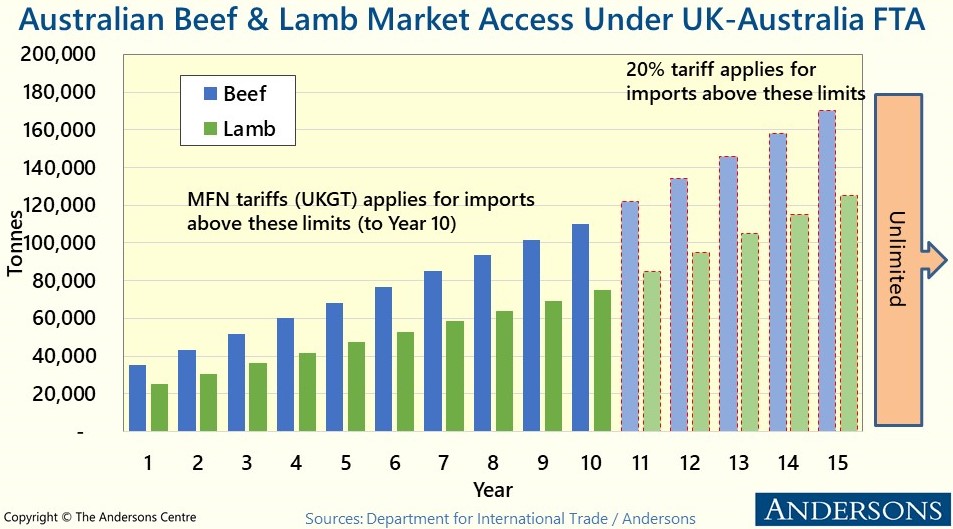

On 14th November, during a House of Commons debate on the Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill, the former Defra Secretary George Eustice severely criticised the UK Government’s negotiating strategy for both trade deals. He singled out the then Trade Secretary, Liz Truss, for particular criticism, especially for imposing an arbitrary target of concluding negotiations with Australia ahead of the 2021 G7 summit. He thought that this severely weakened the UK’s bargaining power. Mr Eustice recalled that there were ‘deep arguments and differences in cabinet’, which were mirrored by friction between Defra and the Department for International Trade (DIT) during the negotiations. He also claimed that the ‘Australia trade deal is not actually a very good deal for the UK’ and that he tried his best when Defra Secretary to address its shortcomings. Specifically, he claimed that there was no need to give Australia (and New Zealand) unlimited access over the longer term for sensitive sectors such as beef and lamb.

From a farming perspective, it is all well and good to criticise the deal. But during his time in Government, Mr Eustice defended it – his comments, therefore, offer scant consolation to farmers who perceive these deals to be a significant threat. Both the Australian and New Zealand agreements will increase the competitive pressure on UK agriculture, particularly in grazing livestock. However, recent studies looking at the impact of these trade deals projected that the impact may be lower than some fear. That said, being the first new trade deals that the UK has negotiated from scratch since leaving the EU, they create an important precedent, and the cumulative impact of multiple trade deals can have a more significant impact.

The UK-Australia trade deal was ratified by the Australian Parliament on 22nd November. The Trade (Australia and New Zealand) Bill is making its way through Westminster. It is currently at the Report Stage, where amendments can still be made to the Bill, before a final third reading and subsequent vote on the Bill in the House of Commons – the date of which has yet to be announced. The House of Lords will also have to vote on the final Bill and they could delay it for up to a year before it would receive Royal Assent (assuming it is passed by the House of Commons).