Tag: Soybean

IGC Global Crop Predictions

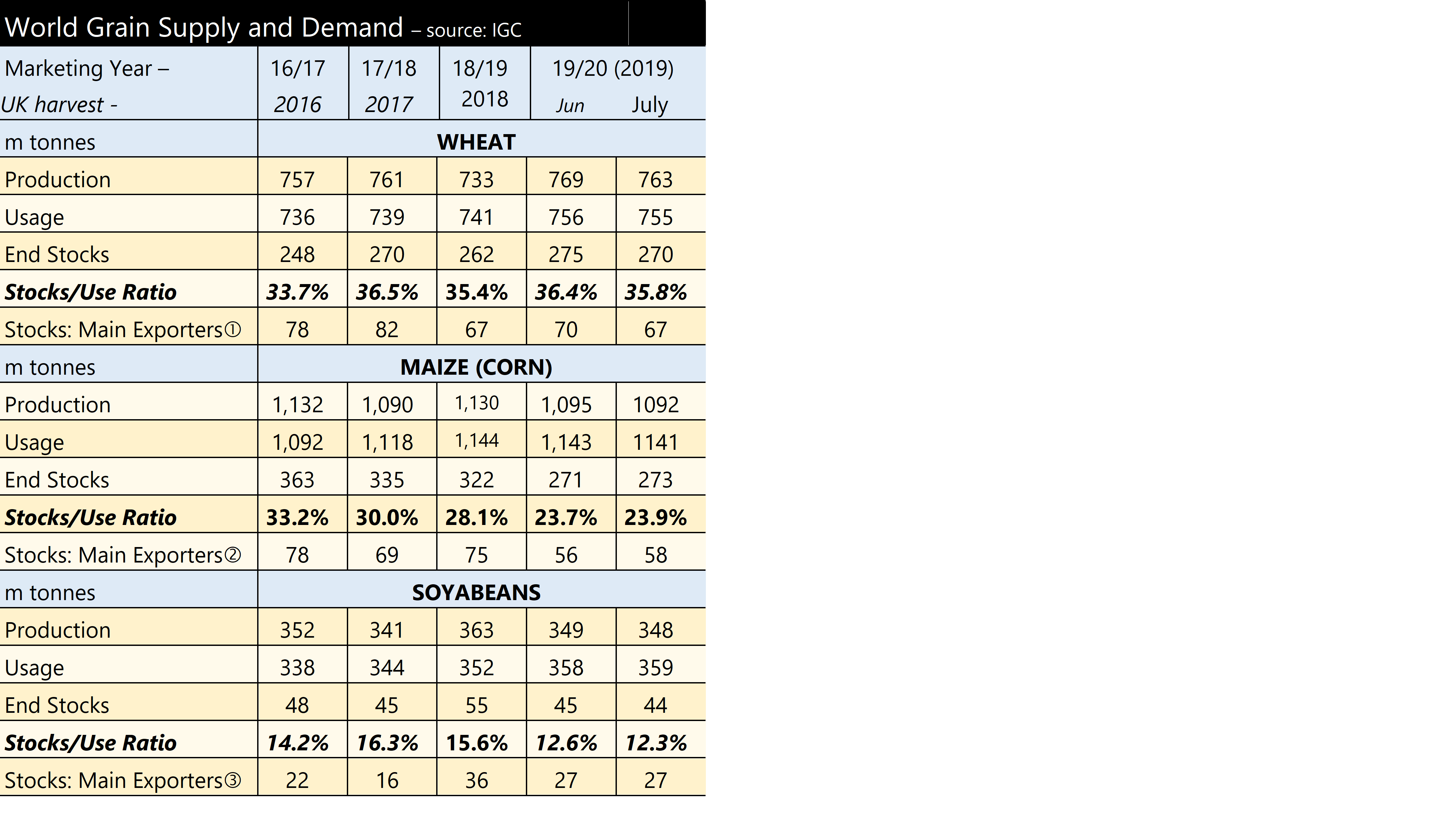

As the northern hemisphere harvest gets underway, the forecasts for global grain output should become more accurate. The International Grains Council (IGC) released an updated forecast at the end of July which is summarised in the table below.

Wheat stocks are expected to rise according to the IGC to levels of 2018/19, or in terms of stocks as a proportion of usage, no real change from last year. However, from last month to this, the harvest expectations have declined slightly, making the stock level more akin to last year. A fall of 5 million tonnes from one month to another sounds like quite a lot but at this time of year when the crop is being gathered, it is minimal and of little impact to prices. Consumers are comfortable at the moment that stocks will be available for them of the quality and specification they require.

The same cannot be exactly said of maize, with production thought 35 million tonnes lower than last year; back to the level seen for harvest 2017. Consumption continues to go up each year, so stocks as a proportion of usage are forecast lower than previous years. The IGC has the stock level falling from 322 million tonnes to 273 million, a decline of nearly 50 million tonnes, or in terms of requirement, from 28% of a year’s requirement to less than 24%. This was already seen in June, but as we enter harvest, the figures will become more reliable. Whilst this is a more dramatic fall of stock and supply level than wheat, it is still not at a level that is making the consumers frantic.

Soya production is though unlikely to be as high as last year, also being closer to the previous year, but with consumption gradually rising each year, stocks are seen falling from 15.6% to 12.3%; potentially bullish for the oilseed (and protein) price matrix.

January Combinable Crop Market Update

Last July, nearby and forward prices of UK wheat on the futures market converged to within £1 per tonne of each other at a spike of £157 per tonne; £15 per tonne higher than the market had been only 3 months earlier. It looked like the start of a bull run. Since then, the market has slipped back nearly £20 per tonne for old crop and about £14 for new crop. Prices for harvest 2019 are somewhere between the two. There is lots of talk of currency causing movements in the value of grains and other commodities, but, back in July, the pound was worth €1.13 (€1 = 88p) and today the exchange rate is the same. In fact the Pound has been relatively steady at these levels of between 88p and 90p since September, and in a slightly larger range since last June. Plus, the independent movement in futures positions clearly cannot be a function of currency as it would affect them both equally, but is therefore a series of grain fundamentals moving separately for each crop. The movements, whilst adding up, have been gradual but consistent. Without much grain crop production news at this time of year and ample supplies to keep the consumers out of the news, price movements are often gentle and less noticeable. But it is still a £20/tonne fall since last summer.

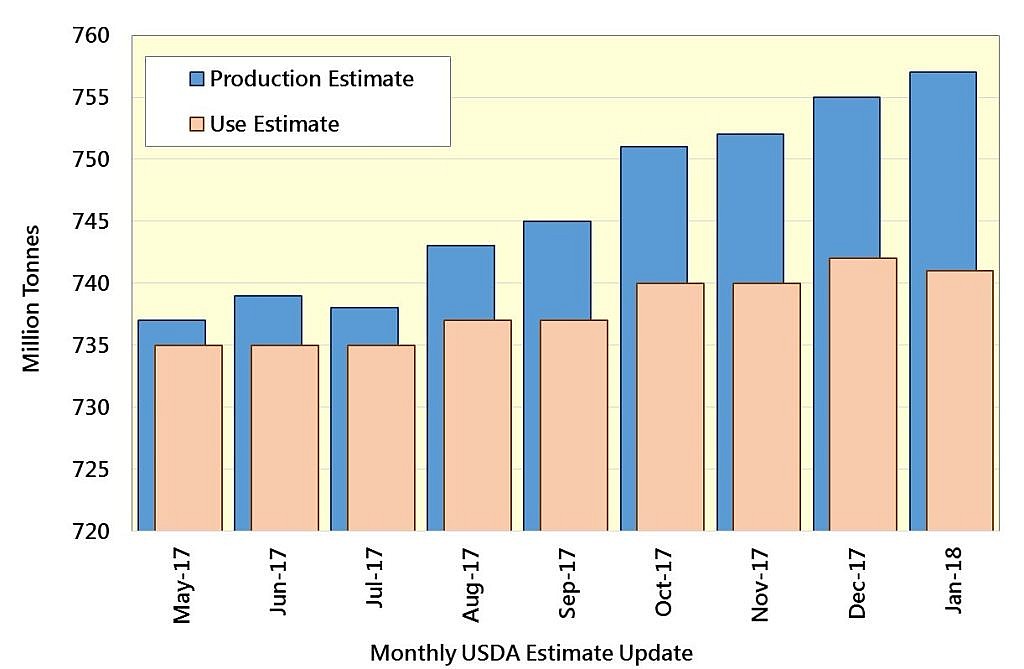

A gentle but persistent underlying bearishness in the market is borne out by the UK futures. This can possibly be explained by the chart below. It shows how the USDA’s monthly expectation (forecast and then estimate) of the 2017 global wheat harvest has changed since the first estimate in May 2017. Its estimate of global production has risen by 20 million tonnes to 757 million tonnes. Whilst this doesn’t sound particularly much, it is approaching a 3% increase in global output expectation; considerably more than the UK produces in total. The USDA’s consumption figures have increased but by much less (6 million tonnes), meaning considerably more crop is now available than was initially thought.

USDA Monthly Global Wheat Production and Consumption Estimates – Harvest 2017

Whilst anything can happen, it does appear that downside currently exceeds upside in the wheat market. We are aware that any information that is reported on (including USDA statistics) is built into the market immediately meaning forecasting further moves is not possible from public information, but a heavy surplus is likely to slow any future bull runs. Indeed, wheat has fallen more than barley this month, and the difference in some regions is now small. We might see some feed consumers switching from barley into wheat.

Global soybean trade can be simplified as either a) from USA or Brazil to China or b) any other trade. Between them, the USA and Brazil account for 83% of global exports, and China alone accounts for 65% of imports. Whilst exports in both countries have been rising, Brazil now outstrips the USA as the major soybean supplier for the world. Indeed, China has been favouring Brazilian beans this year. This is possibly a price issue, with the Brazilian Real weakening making them more competitive, but also as their protein is consistently higher. China buys soybean, primarily for the meal, not the oil. We would generally expect a weakening of US prices to have a greater impact on EU oilseed (and pulse) values than Brazilian, being more closely connected to the EU marketplace, however, the overall balance between supply and demand is the ultimate arbiter of the base price for commodities.

Whether higher protein adds value in beans is a moot point: A recent seminar on pulses held in Peterborough, was told by a prominent pulse buyer that whilst higher proteins is preferable to lower proteins in beans when it comes to securing export outlets, protein levels do not attract higher payments and growers would not receive more. In other words, the key in the UK when growing pulses is to go for yield, and not protein. At least not until the buyer recognises it as preferable by way of price differentiation.