Arable markets have continued to react to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. May-22 UK feed wheat futures have moved up further, now trading around £320 per tonne. In the short-term, prices for commodities and inputs will be driven by uncertainty in Ukraine. The re-escalation of conflict in the east of the country, where much of Ukraine’s wheat and barley crop is grown, will continue to drive prices.

While the war in Ukraine has been the key driver of grain markets over the past three months, there are also other factors driving prices.

Severe drought in parts of the US wheat belt, has seen US wheat crop conditions rated poorly. In the most recent USDA report (18th April 2022) 37% of the US winter wheat crop was rated as being in ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ condition, the highest proportion for this time of year since 2018. Difficult crop conditions at this time of year do not guarantee low production, in 2018 yields in the US, whilst down, were ahead of the five-year average even after crops were rated poor earlier in the season. However, the crop needs rainfall, which looks lacking at present.

On top of the concerns for the US wheat crop, the US maize crop is also getting smaller. Reports suggest farmers in the US are opting for soyabeans over maize, driven by lower costs of production. The combination of a smaller US winter wheat crop and smaller than expected maize crop will support new crop grain prices.

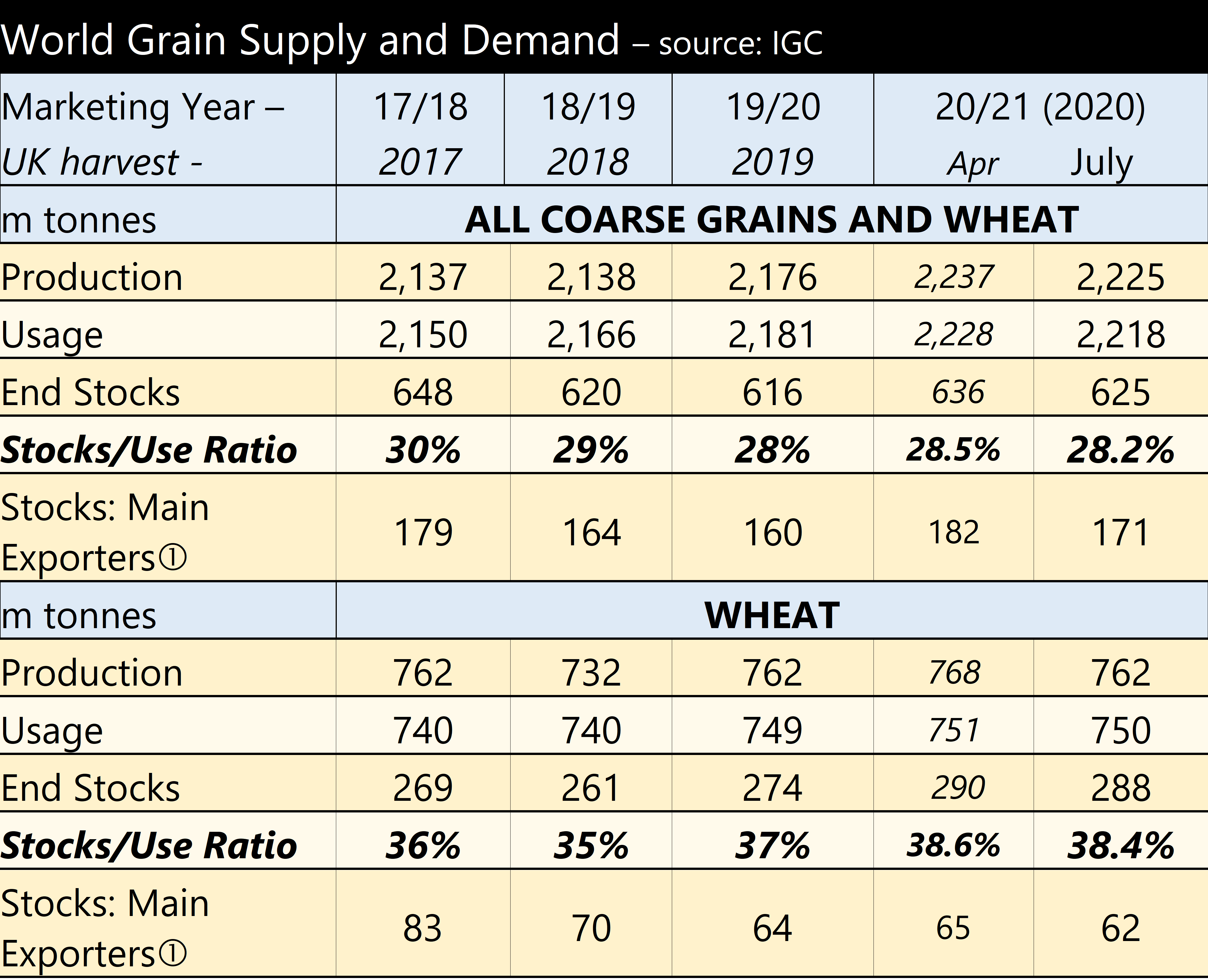

The latest International Grains Council (IGC) supply and demand estimates, support the view of tight markets. World grain closing stocks are forecast to fall by 26.5 million tonnes from 2021/22 to 2022/23. Major exporters’ closing stocks of grain drop by 14.2 million tonnes.

It is worth adding that owing to the situation in Ukraine, all forecasts should be treated with caution.