On 13th June, the UK Government introduced the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol Bill to the House of Commons. The highly controversial Bill, if enacted, would dis-apply large swathes of the NI Protocol which was agreed between the UK and the EU as part of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiations. The Bill’s legal text which is highly complex and potentially far-reaching drew harsh criticism from multiple sources. It has been met with particular disdain by the EU which sees the Bill as a breach of international law and the Commission is set to respond in the near future. At a top-level, the Bill seeks to do three things;

- Disapplies large parts of the Protocol: relating to most provisions that apply EU rules on the movement of goods into NI.

- UK’s Protocol alternative: is outlined and the UK Government provides some guidance on how it would be implemented.

- European Court of Justice oversight: the Bill would remove the Court’s direct jurisdiction and the role for EU institutions

In essence, the Bill is effectively rewriting the Protocol, in a unilateral manner, outside of the structures agreed by the UK Government and the EU. Whilst the political fall-out will continue to generate intense debate, it is the accompanying policy paper which provides practical insights on how the Bill would work and the implications for agri-food. The key points are;

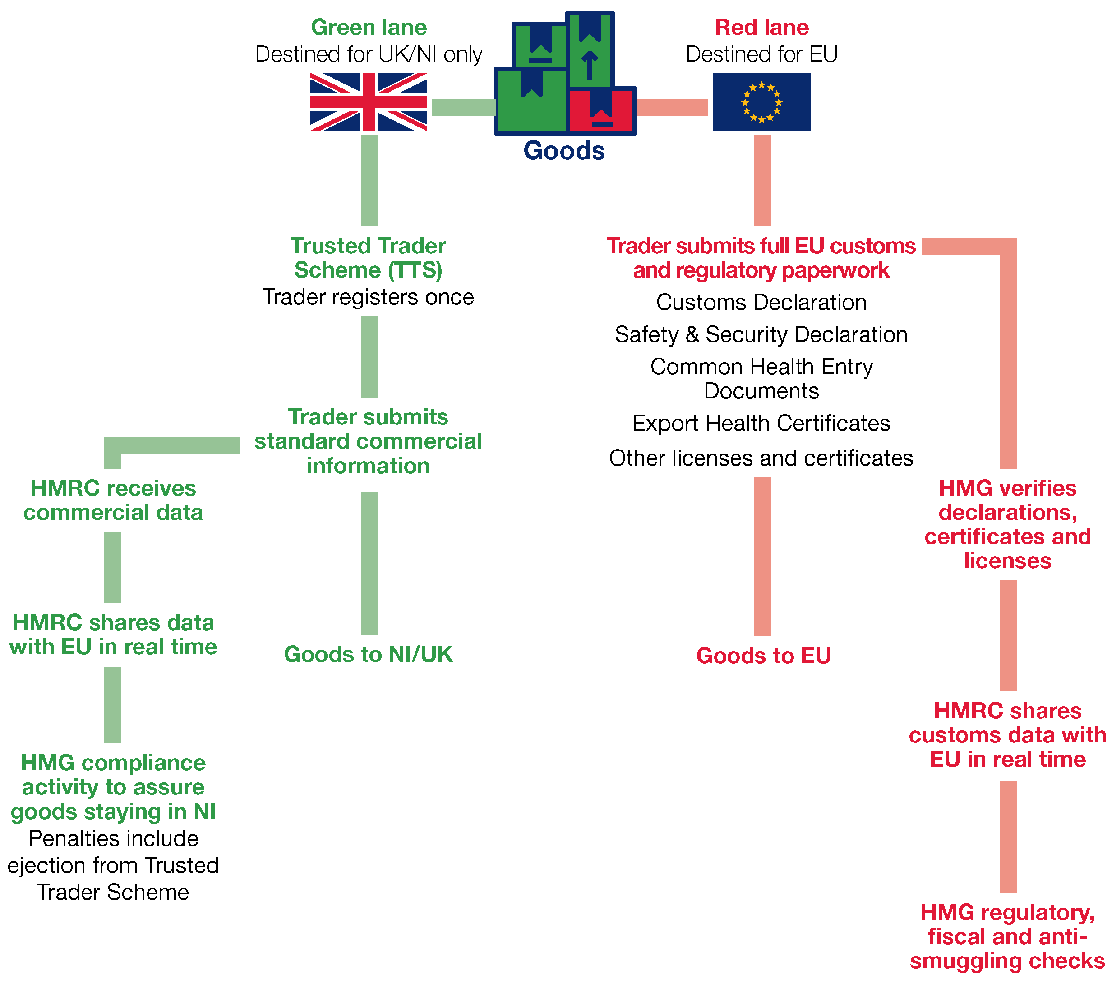

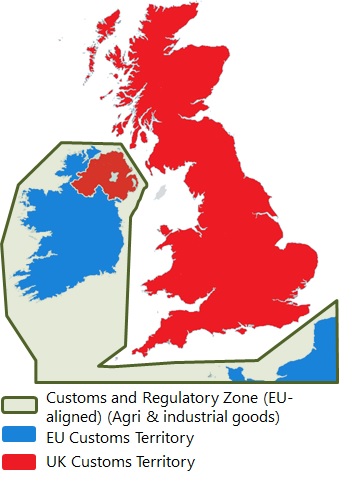

- Establish new ‘green channel’ arrangements for goods staying in the UK: it is claimed that this would fix the burdens and bureaucracy caused by the application of EU Customs and SPS rules. This channel would only be available to firms registered as ‘trusted traders’ and this scheme would be overseen by UK Authorities. Goods moving on to the EU or moved by firms not in the trusted traders’ scheme would use the ‘red lane’ and be subject to the full range of regulatory checks. This would significantly reduce the sometimes complex certification requirements for agri-food produce. Here, the UK proposals are not that far from the EU proposals published last October which suggested an ‘Express Lane’ for goods moved by trusted traders which would be consumed in Northern Ireland.

- Establish a new ‘dual regulatory’ model: this is intended to provide flexibility for NI firms to choose between UK or EU rules on product standards. It is intended to remove barriers to trade within the UK internal market and the UK Government claims that it will encompass robust commitments to protect the EU Single Market. For agri-food, goods could only move from GB to NI under the trusted trader scheme (otherwise they would be in the red lane and subject to checks). There would be robust penalties for violations. The EU strongly objects to this proposal on the grounds that it undermines the integrity of its Single Market. There are also challenges around the bureaucratic complexities involved with dealing with two regulatory systems. Major NI agri-food businesses are also against these proposals as it would scare-off overseas customers from purchasing NI produce as they would be unsure on which standards the products are adhering to and would be deemed too complex and risky.

- State Aid and VAT: the UK Government states that the Protocol restricts the UK from providing the same tax and spend policies in NI as the rest of the UK—with little room for flexibility. This aspect of the Protocol was insisted upon by the EU so that there was a level playing field between NI and the EU Single Market and that NI firms, or GB firms with operations in NI, did not gain an unfair advantage. The new Bill gives the UK freedom to disapply these rules so that NI can have the same tax rules as other parts of the UK. Again, the EU strongly objects to these proposals.

- Role of European Court of Justice (CJEU): would be removed in dispute settlement and would provide the means for UK Authorities and Courts to set out the arrangements which apply in Northern Ireland. This is also highly controversial from an EU perspective as it would not have agreed the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the UK if the CJEU did not have ultimate oversight over the NI Protocol.

Whilst the full EU response is awaited, it has confirmed on 15th June it is restarting the legal proceedings it had initiated last year against the UK Government for its unilateral extension of grace periods for checks on products such as sausages and mince. These had been suspended for almost a year to facilitate negotiations on addressing the Protocol issues. The EU response is also likely to state that it reserves the right to enact much more stringent measures if this NI Protocol Bill becomes law in the UK. This would include suspending key aspects of the TCA or introducing some tariffs on UK exports to the EU. That said, the EU will also be keen to get the UK back to the negotiating table and the Commission has set-out further proposals on how it thinks the outstanding issues on the NI Protocol should be dealt with.

From an agri-food perspective, it is important to note that the House of Lords will vote against this Bill, thus delaying its enactment for at least a year. This gives time for further negotiations to take place. However, additional negotiating time has been wasted in the past. Breaching International Law (which legal experts almost entirely agree would happen if this Bill were to be enacted)) is not the way to build trust. What is needed now is quiet and determined diplomacy to reach a deal that all parties can live with.

NI agri-food businesses are adamant that the Protocol delivers major benefits in enabling NI to access the EU Single Market whilst having unfettered access to GB. As we have mentioned previously, a UK-EU veterinary agreement would help greatly to reduce the burden of checks, not just GB to NI but also GB to the EU. On this, the EU needs to be more flexible. The UK will not opt for a Swiss-style veterinary agreement as that would mean following EU rules for the whole of the UK. A bespoke veterinary agreement should be a key part of the framework to resolve the remaining Protocol issues.