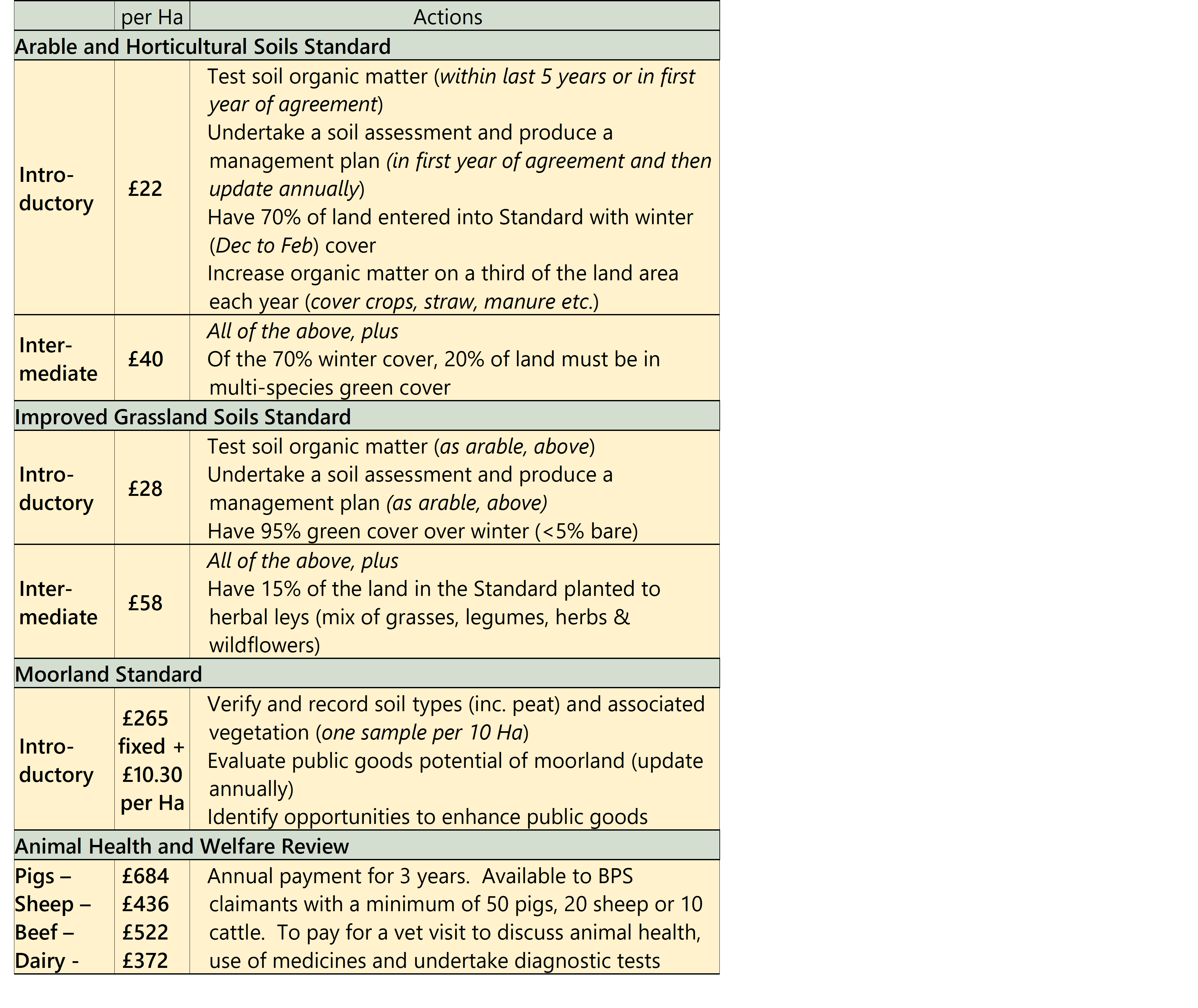

Rents

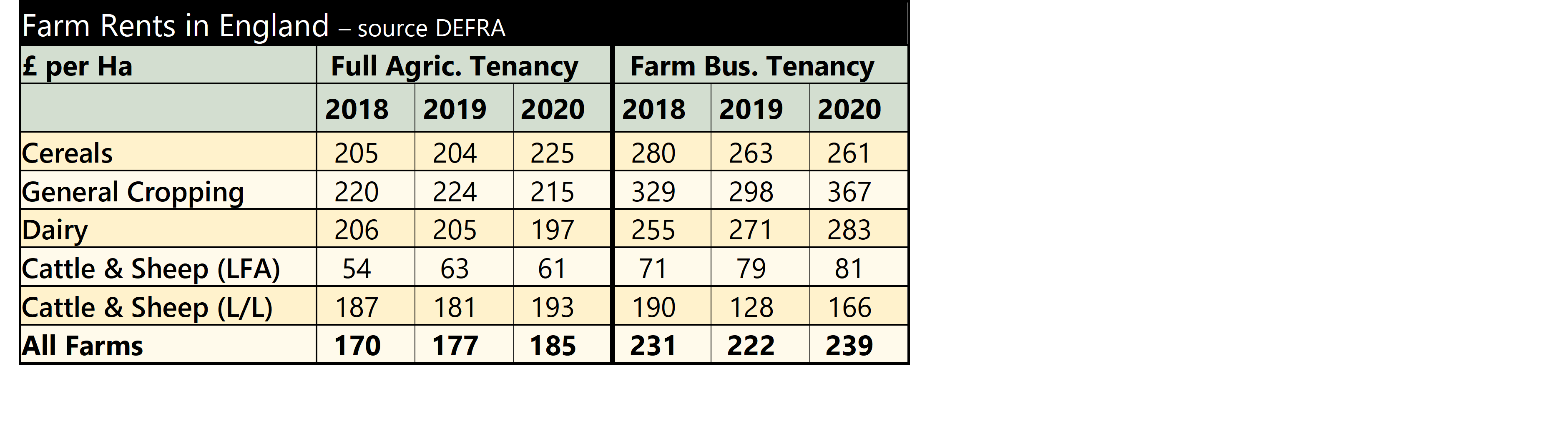

The latest agricultural rents data shows quite a mixed picture. Some sectors have experienced a rise in ‘full’ Agricultural Holdings Act (AHA) rents whilst at the same time seeing a fall in FBT rents; for other sectors it is vice versa. The table below shows a summary of the last three years. Defra’s Farm Rents publication uses data from the Farm Business Survey. Due to the time taken to collect the data, it is somewhat historic. The figures just published are for the 2020/21 year, March to February, (shown as ‘2020’ in the table below). The full statistical notice can be found at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/farm-rents.

The overall average annual rent for AHA tenancies in 2020 has risen by 5% compared with 2019. Average Farm Business Tenancy (FBTs) rents, after an annual decline in 2019, have also risen, up by 8% to £239 per Ha. Cereals farms on AHA Tenancies recorded a 10% rent increase, whilst FBT rents declined marginally. Although only a small decrease this year, it can be seen this is the second year in a row that Cereal FBT rents have fallen. However, they still remain 16% higher than AHA rents. The only other farm type to experience a rise in AHA rents in 2020 compared to 2019 is Lowland Cattle & Sheep, again after a drop in 2019. However, Lowland cattle and sheep farms have also seen a significant (30%) increase in FBT rents after a large decline in 2019, perhaps reflecting better conditions in the livestock sector. Dairy farm rents show a decline in AHA rents but continue to see steady increases in FBT rents, perhaps a reflection of progressive farms keen to expand in the sector.

As written previously, data on rents can fluctuate annually and one year’s information should not really be taken in isolation. In general, rents have been on an upward trend, but looking to the future it would be expected that, as the BPS is phased-out, then overall rents will fall.

As written previously, data on rents can fluctuate annually and one year’s information should not really be taken in isolation. In general, rents have been on an upward trend, but looking to the future it would be expected that, as the BPS is phased-out, then overall rents will fall.

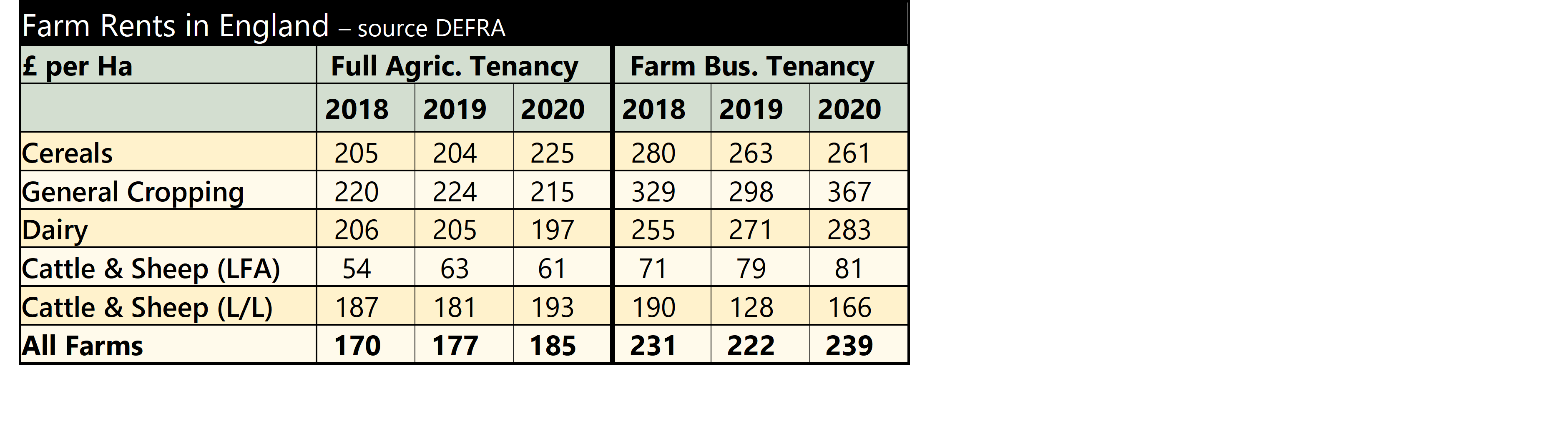

Land Values

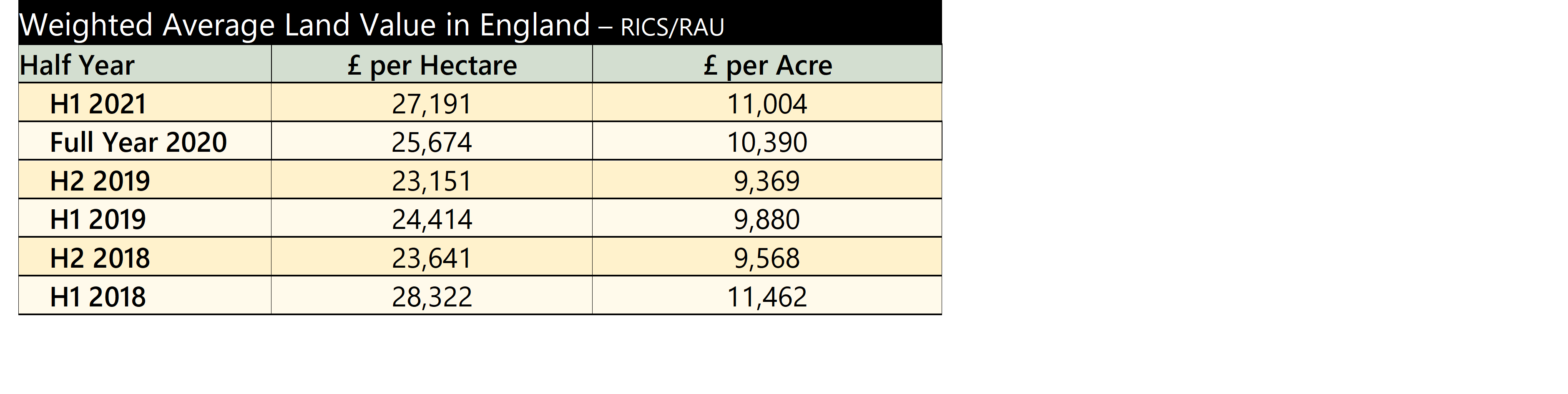

Also a little historic is the RICS/RAU Farmland Market Directory of Land Sales. As previously reported, the RICS/RAU Farmland Market Survey has been discontinued. However the Farmland Market Directory of Land Sales provides a Weighted Average – comparable with the figures in the previous Farmland Market Survey. The Weighted Average Value excludes those sales which have been identified as having a residential value of more than 50% and a regional adjustment is also made. The most recent values are for the first half of 2021. This shows the Weighted Average value per hectare was £27,191 per hectare (£11,004 per acre). This compares with £25,674 per hectare (£10,390 per acre) for the full year 2020. The table below shows the last six surveys.

As can be seen land values have remained robust even through the uncertainties of Brexit and Covid. Demand remains strong, with rollover money and lifestyle buyers helping to drive the market.

As can be seen land values have remained robust even through the uncertainties of Brexit and Covid. Demand remains strong, with rollover money and lifestyle buyers helping to drive the market.

As written previously, data on rents can fluctuate annually and one year’s information should not really be taken in isolation. In general, rents have been on an upward trend, but looking to the future it would be expected that, as the BPS is phased-out, then overall rents will fall.

As written previously, data on rents can fluctuate annually and one year’s information should not really be taken in isolation. In general, rents have been on an upward trend, but looking to the future it would be expected that, as the BPS is phased-out, then overall rents will fall.  As can be seen land values have remained robust even through the uncertainties of Brexit and Covid. Demand remains strong, with rollover money and lifestyle buyers helping to drive the market.

As can be seen land values have remained robust even through the uncertainties of Brexit and Covid. Demand remains strong, with rollover money and lifestyle buyers helping to drive the market.