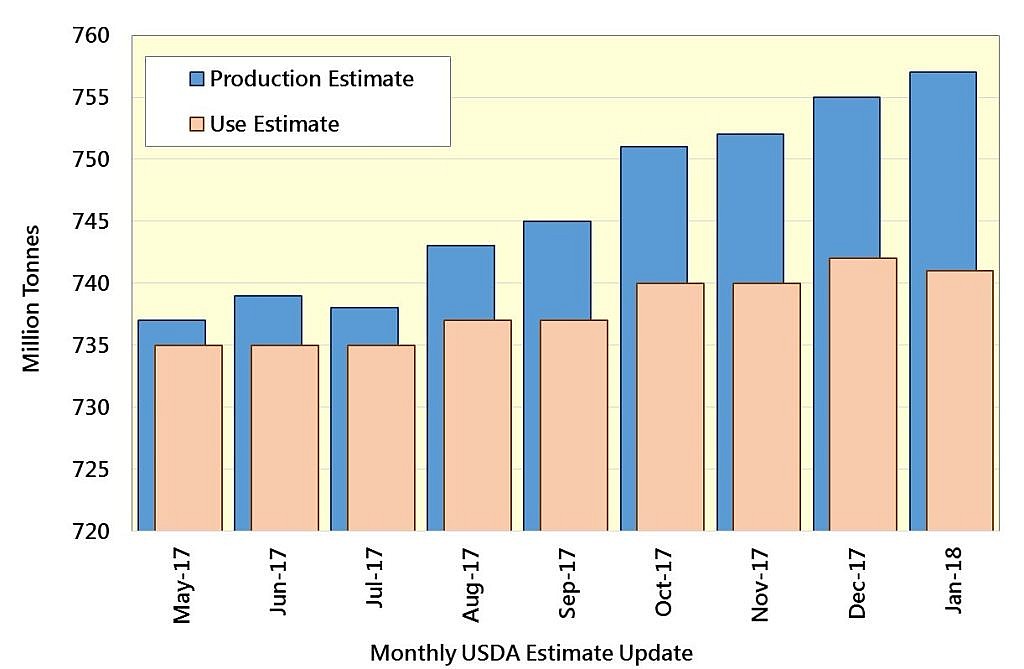

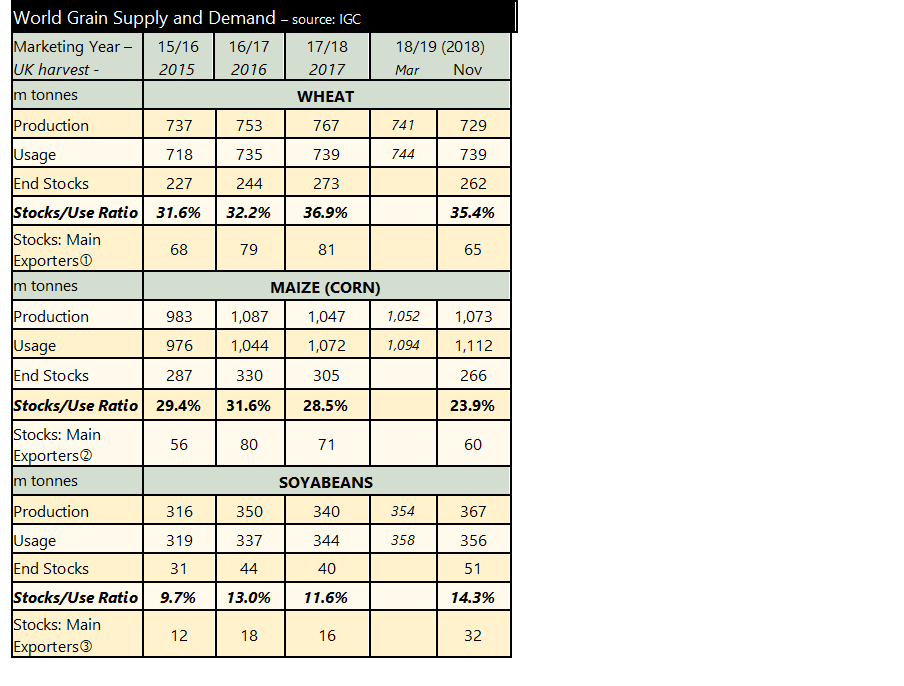

This time last year we took a look at the global grain supply and demand figures supplied by the International Grains Council (IGC). The IGC is a politically independent body, so therefore theoretically has greater credibility than the US Department of Agriculture, the other major organisation that publishes global grain statistics. The only issue is that the IGC has a secretariat of about 20 economists, and the USDA, some thousands, with people on the ground in every region of the world. In any event, the figures from the two organisations are often relatively similar!

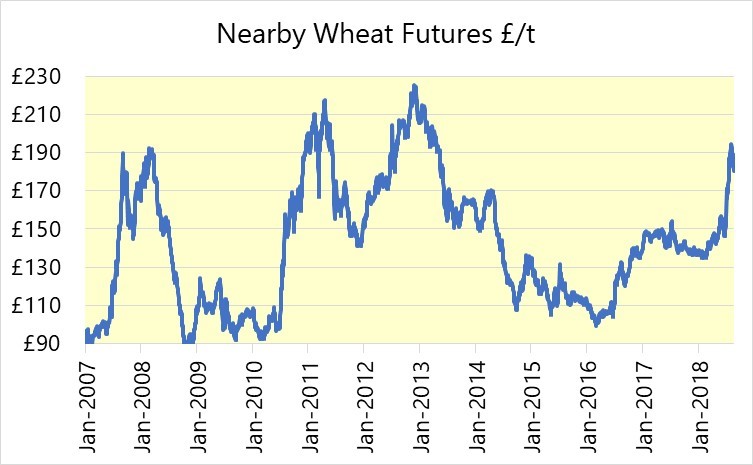

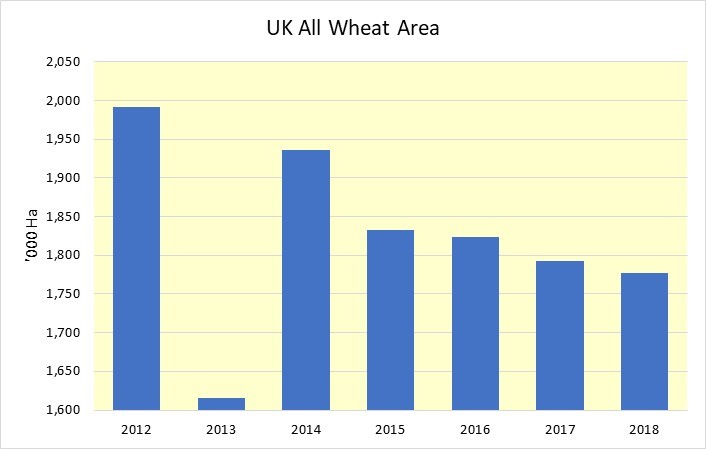

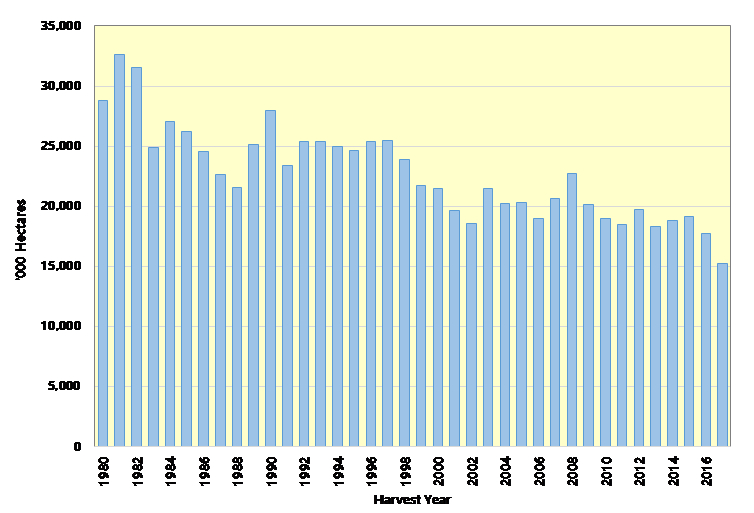

Twelve months ago, we discussed how wheat stocks were at their highest ever, in physical terms. This year, running at 38 million tonnes (or 5%) less, the fundamentals are looking more positive for grain long-holders (farmers). Furthermore, as can be seen from the change in pre-harvest expectations back in March 2018, to the last set of figures in November, the reality of what has been harvested in the 2018 year (and continues to be cut in the Southern Hemisphere) is lower than initial estimates; again, bullish for price. The stocks to use ratio is lower than last year at 35.4%, but still considerably higher than the previous two years, suggesting accessing the right specification and location of wheat by consumers is unlikely to be challenging to buyers in the coming season. A lower level of stocks held by exporters offers a glimmer of hope to those waiting for prices to rise, but it also suggests that importers have more stocks so might buy less.

17/18 figures forecast; 18/19 estimates 1 Argentina, Australia, Canada, EU, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, US 2 Argentina, Brazil, Ukraine, US 3 Argentina, Brazil, US

A look at the maize figures shows a different story; one of rising stocks and increasing availability. This indicates that crops grown for energy alone (animal feed and bioethanol purposes primarily), are in relatively bounteous supply. It suggests that the premium for milling varieties might benefit in the coming year. However, in another interesting twist to the story, as stock levels are expected to be so much lower this year than for the last few (because of rising usage), the stock:usage ratio is seen falling. Furthermore, the Egyptians (the world’s largest wheat importers) have been buying Russian wheat at prices above anything they have paid for 4 years. This, coupled with a weakened Sterling because of recent political shenanigans, supports UK wheat prices. We are still a long way from harvest 2019 (the IGC hasn’t even started to forecast supply and demand for it as yet). There was a view that, barring major weather events, as we approached harvest 2019 there would be a downwards ‘correction’ in wheat prices as availability rose. There is now perhaps a lesser chance of this happening.

Barley markets are quiet ahead of Christmas, with few buyers or sellers, including no new export business. Premium samples of malting barley retain a good premium for those still unsold.

The oilseed marketplace has seen prices move a little more than grains this month, partly because of the Chinese/US politics which affect soy beans but also as the southern hemisphere crop is being harvested and some is already sold and loading for delivery into the EU.