NAO Report on No Deal Readiness

On 24th October, the National Audit Office (NAO) released its latest report on the UK’s preparations for a No Deal Brexit. Although the report’s scope examines the economy in general, the estimates provided indicate stark implications for the agri-food sector. Key findings include;

- Between 145,000 and 250,000 traders would need to make customs declarations for the first time in the event of a no deal

- HMRC estimates that it would have to deal with 260 million customs declarations per annum, as opposed to the current 55 million, nearly a five-fold increase.

- 11 of 12 critical systems needing to be replaced or changed to manage the border were at risk of not being delivered on time and to acceptable quality. Several of these systems including the TRACES replacement system which would need to be developed by the UK to manage sanitary-related border movements are at major risk of not being delivered by Brexit day.

- There is an elevated delivery risk due to the high interdependence between ‘at risk’ government programmes reliant on another ‘at risk’ programme. For example, seven of the most critical border systems are interdependent with the Customs Declaration Service (CDS) and/or its legacy system CHIEF (Customs Handling of Import and Export Freight); and all must be ready on day one for the border to operate as planned.

- New infrastructure to track and physically examine goods cannot be built before March 2019. Without this, the UK will not be able to fully enforce compliance regimes at the border on day one. With approximately 100 working days until Brexit, this is unsurprising.

- Border Force intends to recruit 581 staff by March 2019 and expects to increase its staff in the months following. However, given uncertainty regarding the future regime, and the length of time it takes to recruit, security clear and train staff, Border Force acknowledges that there is a significant risk that it will not deploy all the staff it plans to recruit by 29 March 2019. The intended numbers of new recruits appears low in comparison with plans by Ireland and the Netherlands to each recruit approximately 1,000 extra customs staff in preparation for Brexit.

- The most complex issues concerning the movement of goods at the border, such as arrangements to apply at the Northern Ireland and Ireland border as well as a system that will allow roll-on roll-off ferry ports and Eurotunnel to operate smoothly still need to be resolved.

As a result, the NAO warns that there will be an increased danger of criminals exploiting any perceived weaknesses or gaps in the enforcement regime. This could lead to an erosion of trust in UK agri-food produce. For example, if non-UK origin beef enters Britain illegally, at a lower price, and is then repackaged to give the impression that it is British beef (at a higher price), then regulatory authorities in both EU and non-EU countries will become very concerned. Given the substantial progress that the UK has made recently in opening markets such as China, a No Deal Brexit has the potential to undo a lot of this valuable work.

Further information on the NAO report is available via: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-UK-border-preparedness-for-EU-exit-Summary.pdf

No Deal Technical Notices

Separately, the UK Government has released several additional technical notices on preparations for a No Deal Brexit. Some notices were also published in August (see previous article) Several of the latest notices are directly related to agri-food and are briefly summarised below.

Farming and Food

- Regulating Pesticides: the UK would establish an independent standalone PPP regime, with all decision making repatriated from the EU to the UK. This would help to ensure that a stable regulatory framework for pesticides is put in place from the point that the UK leaves the EU and would retain the two main directly applicable EU regulations in national law, through the provisions of the EU Withdrawal Act. This is intended to ensure that human and plant health standards continue to be upheld whilst making it as easy as possible for businesses to place products onto the UK market. Other points include;

- All current active substance approvals, PPP authorisations and MRLs would remain valid in the UK upon departure in March 2019. Initially, there would be no policy changes, aside from technical amendments to make EU law applicable in a UK context. However, long-term the notice acknowledges that the UK could diverge from the EU in certain areas in due course. This point will be particularly relevant to decisions on glyphosate renewal for example.

- After departure, all applications for products to be authorised in the UK would need to be considered via a national regime and applications for EU approvals would need to be made separately.

- The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) would continue to operate as the national regulator. Applications under the national regime after Brexit would need to be made to HSE, in the same way as now.

- Other processes carried out at an EU level including by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) would be converted into a national process and processed as part of a national regime if they were applicable to the UK. Decisions on MRL approvals currently undertaken at EU level would be replaced by a new UK statutory register in the form of an online database.

- Importantly, to ensure that processes run smoothly, there would be an extension of three years to active substance approvals which are due to expire in the three years after the UK leaves the EU. Also applications being considered by the UK at the point of exit would continue to be progressed via a national regime.

- Elements of the current regime, which rely on EU membership, would no longer be able to operate in a no deal scenario e.g. the arrangements whereby EU countries can choose to mutually recognise product approvals and also parallel trade permits. To address this, parallel trade permits in force at the point of exit would remain valid for a transitional period of two years after the date of exit, or the extant expiry date (whichever is sooner). After expiry, businesses would need to obtain authorisations for marketing and use of their products in the UK.

- A transitional period for seeds which have been treated with PPPs authorised for that use in other EU countries would also be provided so that they could continue to be lawfully marketed at the point of departure from the EU and could continue to be placed on the UK market for a period of three years after Brexit.

Having a transition period of three years after Brexit is wise although some might question whether it is enough time to adapt, particularly given the timelines required to gain regulatory approval in some cases. Further information is available via; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulating-pesticides-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/regulating-pesticides-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Manufacturing and marketing fertilisers: again current domestic regulatory framework would remain in place but would be separate to the EU framework. There would be some implications for material labelled ‘EC fertiliser’ in accordance with the EU Regulation and sold in the UK:

- There would be a suitable time-limited adjustment period during which ‘EC fertiliser’ could be placed on the UK market as now, to ensure continued supply. There would also be consultation with industry as to how long this time period needs to be so that UK or EU manufacturers would not have to change labels immediately. However, the Government envisages that it would be no more than two years.

- There would be an option to use a new ‘UK fertiliser’ label for fertilisers placed on the UK market after Brexit, in accordance with the EU Regulation as converted into UK law

- Upon the end of the time-limited adjustment period, fertilisers placed on the UK market would need to comply with the current domestic regime or with the requirements of the new ‘UK fertiliser’ regime.

- The Government would also publish a new list of laboratories approved to test to the standards required for the new ‘UK fertiliser’ label.

The notice also claims that UK manufacturers would still be able to manufacture their products as ‘EC fertilisers’ in accordance with the EU framework and UK companies could still export ‘EC fertilisers’ to the EU. However, exports would have to ensure that they comply with applicable EU regulation, including the requirement that the manufacturer is established within the EU, and that any sampling required is undertaken by an EU-approved laboratory. The notice also claims that there would be no material change for users of fertilisers as long as fertilisers that are marketed meet the requirements set-out. Further information is available via: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/manufacturing-and-marketing-fertilisers-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/manufacturing-and-marketing-fertilisers-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Plant variety rights and seed marketing: EU plant variety rights granted up to the point of departure, including those held by UK businesses, would continue to be recognised in the remaining 27 EU countries. Those rights would also automatically be recognised and given protection under UK legislation, without rights holders needing to take any action. For applications that have been applied for but not approved by March 2019, an application for rights in the UK would need to be made to APHA, following the normal process for UK plant variety rights, and using the same priority date and DUS tests. New applications from that date would require two separate applications (one for UK and another for EU-27). For protection of rights after departure, a separate application would need to be made to the APHA in addition to the EU equivalent.

For seeds and propagating material, varieties registered solely via UK National Listing would no longer be listed on the EU Common Catalogue and would not be marketable in the EU. To ensure that UK product could be marketed in the EU, breeders would have to ensure that the variety is listed on the EU Common Catalogue and the seed would have to be certified by an EU-approved certification body. Whilst the UK will apply to the EU to have its certification processes recognised as equivalent, this recognition cannot be guaranteed upon departure and may take 12 months to get approval. Further information is available via: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/plant-variety-rights-and-marketing-of-seed-and-propagating-material-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/plant-variety-rights-and-marketing-of-seed-and-propagating-material-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Breeding animals: upon departure, UK-recognised breed societies and operations involved in live animals and germinal products trade would no longer be recognised societies or operations in the EU and therefore would be ineligible to enter their pedigree breeding animals into an equivalent breeding book in the EU and would have no right to extend a breeding programme into the EU. However, the EU has stated that breeding bodies meeting its requirements will be permitted to make entries as a third country but that animals would need to be accompanied by a zootechnical certificate. Defra is making preparations to enable zootechnical stakeholders to be listed as approved third country breeding bodies with the EU Commission so that thereafter these bodies can issue zootechnical certificates. Arrangements for EU-registered breeding bodies operating in the UK would not change initially and would have access to the UK in the same way as they do now. For further information visit; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/breeding-animals-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/breeding-animals-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

There are also additional notices related to;

- Importing and exporting plant products under a no deal scenario – further information is available via; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/importing-and-exporting-plants-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/importing-and-exporting-plants-and-plant-products-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Importing animals and animal products – more information is available at; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/importing-animals-and-animal-products-if-theres-no-brexit-deal/importing-animals-and-animal-products-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Exporting GM and animal feed products – see https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/exporting-gm-food-and-animal-feed-products-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Producing and labelling of food – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/producing-and-labelling-food-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Health marks on meat, fish and dairy products – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-marks-on-meat-fish-and-dairy-products-if-theres-no-brexit-deal

- Other technical notices: covering a wide range of issues such as regulations for drivers and commercial vehicles as well as general business regulation are accessible via: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/how-to-prepare-if-the-uk-leaves-the-eu-with-no-deal

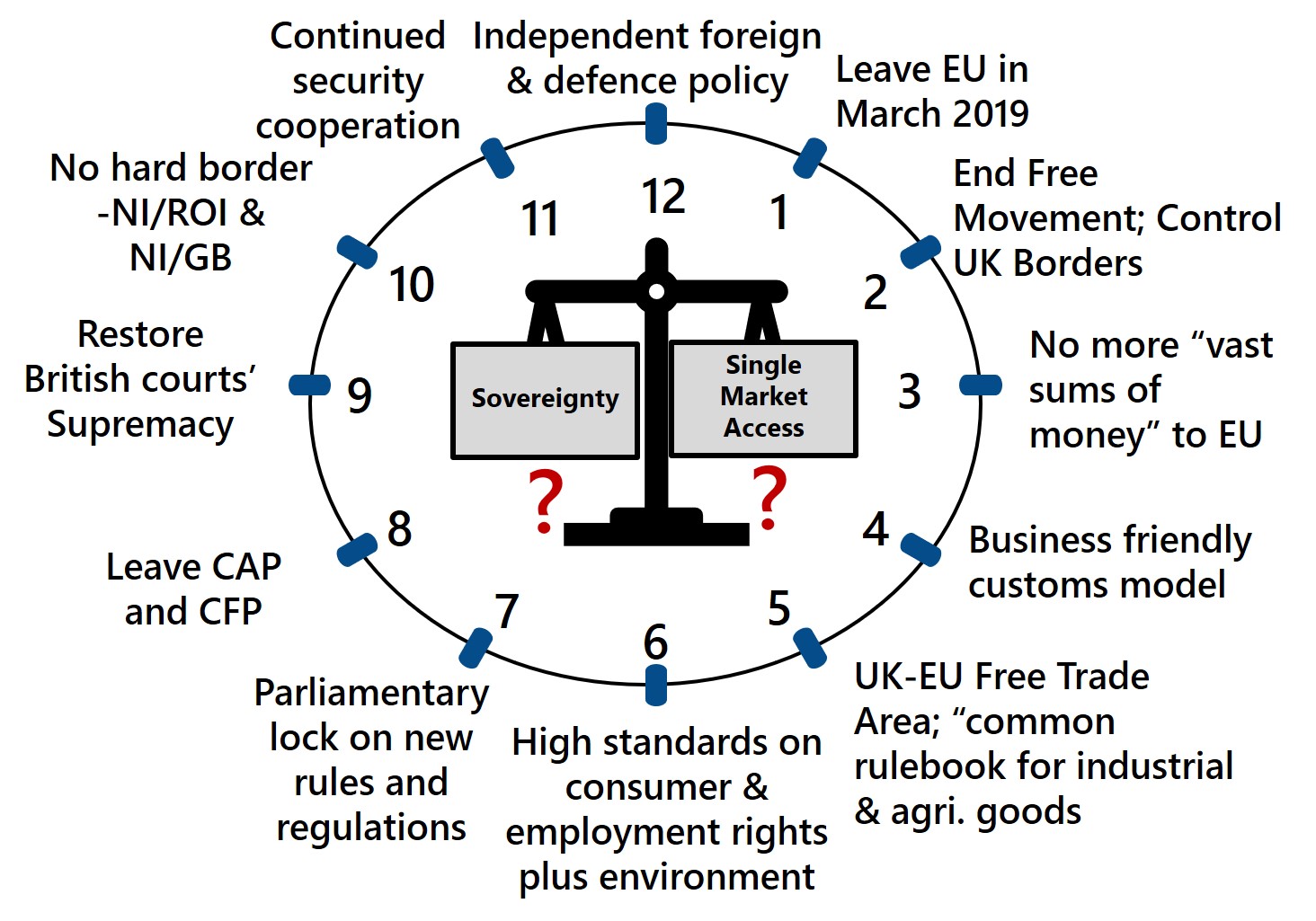

Whilst comment has not been made on all of the technical notices related to agri-food trade, the notices examined above, as well as the notices covered in August, reveal the eye-watering scale of the challenge facing UK Government and businesses if a No Deal Brexit comes to pass. In addition to the Government not being ready as reported by the NAO above, it is apparent that businesses are not prepared either. At a Brexit Select Committee hearing on 24th October, it was suggested that businesses have had more than two years to prepare for a potential No Deal and should have been doing more in terms of preparation. Given that the Government’s initial batch of technical No Deal notices were only published from August, comments such as this are unjustified. Businesses are facing three or more different scenarios by March. To adequately plan for a no deal would require large investments in many cases which would be wasted in the event that a deal was struck. Businesses should not be blamed for the situation that the country now finds itself in. The Government needs to continue its focus on achieving a smooth and orderly Brexit process and to avoid a No Deal scenario in March 2019.