Having been agreed on Christmas Eve and becoming effective just over one week later, it is unsurprising that challenges have arisen for agri-food traders as a result of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). The TCA (click here for summary) is perceived by many to be a ‘thin’ deal as it only focuses on delivering tariff-free and quota-free trade in goods; it delivers little in terms of services and reducing trade friction (non-tariff barriers).

It is in relation to the latter that agri-food trade has been significantly affected, as the EU’s border controls on UK exports became effective immediately. Trade frictions have been experienced in two key areas:

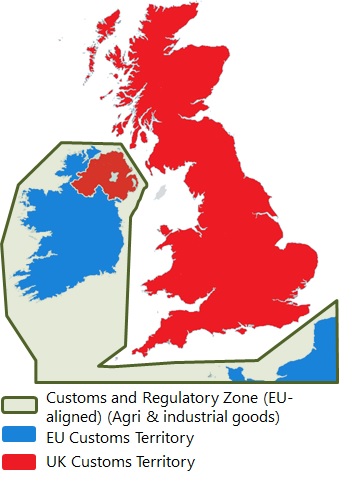

- Customs and Sanitary & Phytosanitary (SPS) controls: whilst there are some limited easements in the TCA on Customs issues (e.g. allowing the pre-lodgement of documents), these are less than many would have hoped for. There are even fewer easements in the SPS area with most of these limited to trade between GB and Northern Ireland. Here, a grace period has been agreed which varies from 3-12 months for specific items. As a result, traders have suddenly been faced with a substantial increase in paperwork with only a few days’ notice. Some have reacted by limiting the number of consignments being shipped to the EU until they get a greater understanding of how the procedures work. Hauliers are unwilling to depart warehouses, processing plants etc. until the paperwork for each shipment is in order. This has meant that port traffic volumes are lower than normal. For instance, traffic on the Dublin-Holyhead route is down by 50%. Volumes traditionally start to increase during the spring. This will be a key test of the ability of border control systems to cope, especially as additional certification and checks will be required on imports into the UK from April and will become fully operational in July.

When both the UK and EU border controls are fully operational, the physical check rates for SPS purposes will be as follows:

-

- live animals – 100%

- minced & poultry meat, dairy products & eggs – 30%

- red meat & poultry products, ambient dairy & eggs, fertiliser – 15%

- semen/embryos, animal by-products – 5%; highly-refined products – 1%

These check rates are effectively the same as the levels of checks that countries trading with the EU on standard WTO MFN terms experience. A proportion of these loads will then be subject to sampling. Selections will be risk-based and shipments could be delayed by several days which will have a significant impact on product value deterioration for the ‘unlucky loads’ affected.

- Rules of Origin (RoO): essentially determine the ‘economic nationality’ of a goods consignment. They aim to prevent goods manufactured in third countries, but routed through the UK (or EU), taking advantage of the zero tariffs. They are particularly significant for industries (e.g. car manufacturing, composite foods) where components/ingredients are sourced from multiple countries. RoO can be expensive for businesses as they have to demonstrate the origin of their product. Whilst the TCA has allowed traders up to 12 months to supply evidence that the goods they are trading between the UK and the EU meet RoO requirements, this is considered to be of limited use as the evidence will still be required. The TCA also allows both the UK and EU to count inputs from the other party when assessing the origin of goods. The UK had wanted to include content from other countries towards meeting the rules of origin requirements (e.g. Canadian wheat used to produce flour for bread-making) but this was rejected by the EU.

There are three general levels of RoO, all of which must be met in order for a good to be traded between the UK and the EU on a tariff-free basis:

-

- Eligibility of goods: do the goods concerned meet the RoO criteria (e.g. ≥85% of content by weight) is eligible for tariff-free trade?

- Certification: can the trader provide adequate certification that the goods are eligible (e.g. Rules of Origin certificate)?

- Shipping and product-specific requirements: has the end-product undergone sufficient processing in the UK/EU before it is subsequently traded. Generally speaking, if there is a change in the tariff code as a result of processing, it would be deemed as sufficient. Other issues can include means of transportation, cumulation arrangements etc. Retailers such as Marks & Spencer who operate a distribution hub covering the UK and Ireland have been particularly affected by this issue. Some of their products are procured from the continent in large consignments and then broken down into smaller consignments for shipment to Ireland. As such products have not undergone sufficient processing, a tariff is payable upon re-entry to the EU.

Generally speaking, if a consignment fails on one of these levels, then the products will fail to meet RoO requirements. This is why Rules of Origin are fiendishly complex.

For each business, it is vital to assess how the TCA will affect the products that it trades, not just between Britain and Europe but also between GB and Northern Ireland, where the NI Protocol is now operational. The challenges here have prompted some suppliers (e.g. Ethical Dairy Company) to cease serving NI customers. From a business perspective, trade has become more complex. But, once businesses become more familiar with the specific requirements that apply to their goods, some of the teething problems will be overcome. However, the UK-EU trading relationship has fundamentally changed, meaning some of the challenges are set to become permanent fixtures. It is likely to mean more single-product, single-consignment loads being traded as opposed to the multi-product, multi-consignment shipments of the past. This will have an impact on value-added, particularly on high-value exports (e.g. high-end prime boneless beef cuts).

Finally, it merits mentioning that in terms of SPS especially, the TCA is a framework that can be built upon. Particularly in terms of reducing the levels of physical checks in the future. However, this is contingent on close alignment on standards between the UK and the EU. Here, the British Government is going to have a delicate balancing act in terms of the trade agreements it completes with other countries and the importance it places on trade with the EU.