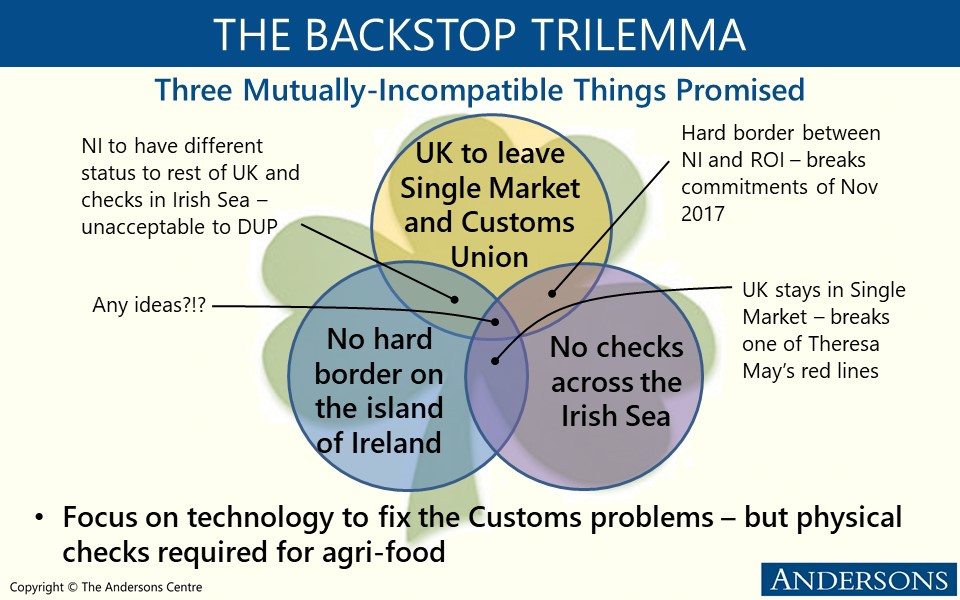

On 27th February, the UK Government and EU Commission reached an agreement on the implementation of the Northern Ireland (NI) Protocol – the ‘Windsor Framework’. The deal emerged after months of, often arduous, negotiations and is heralded as a major breakthrough by both the UK and EU negotiators. It is hoped that this framework will resolve the thorniest issue of the entire Brexit process and has been welcomed by most Northern Irish stakeholders, although the DUP have yet to give an official view on the Framework, which is not expected until April.

The key aspects of the agreement are:

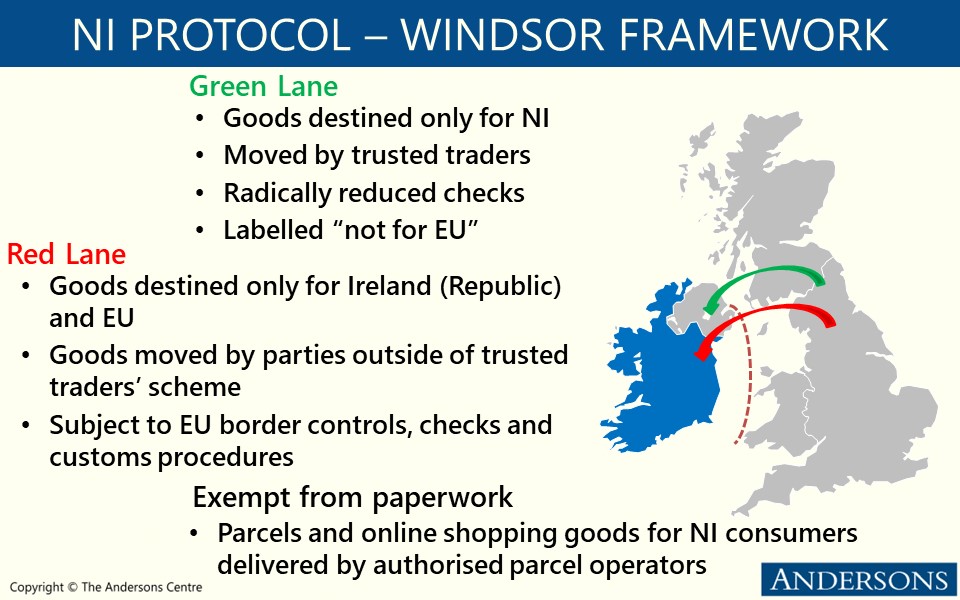

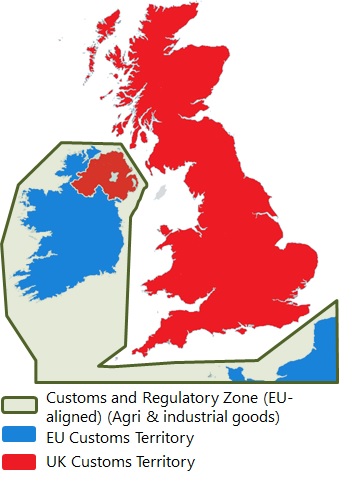

- Customs Procedures for Goods: there will be a ‘green lane’ for goods moving from Great Britain (GB) into NI which will be consumed in Northern Ireland and not deemed to be at risk of moving into the EU Single Market. For such goods, nearly all customs procedures will be scrapped. Goods deemed to be at risk of moving into the EU Single Market will be moved through a red lane, where EU border controls will apply.

- Chilled Meats: products such as sausages which are sold in GB supermarkets will also be available in Northern Ireland, provided that they are shipped into Northern Ireland by trusted traders. Chilled meats are usually prohibited from import into the EU Single Market or require arduous certification procedures (sometimes hundreds of certificates for a container with chilled meat and animal products for the retail sector). This will now be replaced by a single document confirming that the goods will stay in Northern Ireland and are moved in line with the terms of the UK’s internal market scheme. This is a significant concession from the EU. It is also a sensible one on the basis that such products are for consumption in Northern Ireland and there is now real-time data on the movement of goods from GB to NI, giving the EU the visibility it needs to ensure that no fraudulent activity is taking place. Any physical or identity checks that do take place will be on a risk and intelligence-led basis, based on decisions by UK authorities.

- Seed Potatoes, Plants and Trees: certain plant and crop products had been either prohibited from entry into NI from GB since January 2021, or required lengthy certification processes. Such trade can now recommence under the provisions of the Windsor Framework. This is seen as a big boost for the seed potato sector in particular. However, seed potatoes will still be prohibited from being sold to the Republic of Ireland.

- VAT and Excise Duties: the NI Protocol’s legal text has been amended so that the UK can set VAT and excise duties for the whole of the UK. It means that the reforms to alcohol duties taking effect in the UK in the summer will now apply to NI, thus lowering the price of beer in NI pubs for instance.

- Parcels and Online Shopping: no paperwork will be required for parcels moving from GB to NI.

- Pet Travel: documentary requirements and associated treatments and inoculations that are usually required by the EU have been removed for travel between GB and NI.

- Applicability of EU Law in Northern Ireland: has been reduced substantially (estimated by the NI Secretary to be 97%) and now only focuses on the ‘minimum necessary’ to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland. The EU notes that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) will still have a final say on Single Market issues. However, it is envisaged that its role will be greatly reduced due to the provisions outlined above and also because of the data sharing, labelling and enforcement procedures within the Windsor Framework. This will help to safeguard the Single Market whilst also giving opportunities to resolve differences without having to revert to the ECJ.

- ‘Stormont Brake’: this new mechanism is designed to give the Northern Irish Assembly the opportunity to pull an emergency brake on EU legislative changes which would apply in Northern Ireland. It is designed to address concerns, particularly amongst Unionists, on what they perceive to be a democratic deficit of the NI Protocol as agreed in 2020.

For the brake to activate, it would require cross-community support and would need a minimum of 30 Assembly MLAs from at least 2 parties to agree to its activation. The EU stresses that this can only be activated in exceptional and emergency circumstances, where there is a significant impact specific to everyday life in Northern Ireland. It is also planned to have greater consultation between the UK and the EU on new EU legislation so as to minimise instances of the Stormont Brake being activated. Once triggered, the UK Government would notify the EU of its activation. The rule in question would automatically be suspended from coming into effect. It could only then be reapplied if the UK and EU jointly agree. If the suspension remains, the EU reserves the right to respond with remedial action to protect its Single Market. For the Stormont Brake to become an option, it requires a functioning NI Assembly and is seen as a bid to get the NI Executive back up and running.

Overall, the Windsor Framework strikes a pragmatic and careful balance between the concerns of the UK Government and Unionists who wish to ensure that Northern Ireland remains an integral part of the UK, and of the EU in ensuring that its Single Market is protected. With hindsight, it was the sort of balance that should have been struck when the original Protocol was negotiated in late 2020, but which ended up being rushed and was negotiated without enough attention to the nuance needed for the unique circumstances of Northern Ireland. Importantly, by giving NI unfettered access to both the UK Internal Market and the EU Single Market, the Windsor Framework gives Northern Ireland the potential for strong economic growth, not just in agri-food but across NI industry generally. Undoubtedly, the Protocol will need further refinements in the years ahead as will the UK-EU trading relationship more generally. This is as it should be, as trading relationships between near neighbours are constantly fine-tuned. The US-Canada relationship is a prime example of this.