Aside from details of the UK’s new Global Tariff regime published on 19th May (click here for article), there have been other notable recent developments in the Brexit negotiations. These relate to the publication of the UK Government’s draft legal text for a UK-EU Comprehensive Free-Trade Agreement (CFTA) and its proposals to implement the Northern Ireland (NI)-Ireland (IRL) Protocol.

Draft UK-EU Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (CFTA)

This draft legal text was published on 19th May and forms a key part of the UK’s approach to the future relationship with the EU. It elaborates on the objectives of the ‘Canada-style’ trading relationship which the Government set-out in February. David Frost (UK’s Chief Negotiator) has insisted that the proposals approximate very closely what the EU has already agreed with Canada and Japan.

However, the EU is insisting that to get the kind of deal which the UK is seeking, it needs to agree to ‘level playing-field’ provisions designed to stop the UK from undercutting the EU’s rules on State Aid, tax, labour and environmental regulation. According to trade experts, the UK’s ambitions in areas such as the mutual recognition of qualifications (e.g. lawyers) goes beyond what is contained in other FTAs, including Canada and Japan. It is seen by Brussels as an attempt to ‘cherry-pick’ aspects of its current access to the Single Market, and the EU is unlikely to offer concessions on this without some commitments to its level playing-field requirements.

Other areas of friction relate to the EU’s demands for access to the UK’s fishing waters, Britain’s objections to any role for the European Court of Justice in overseeing any eventual deal and arrangements for the implementation of the NI-IRL Protocol (see below).

The draft legal text (292 pages) contains limited (six) references to agriculture and these primarily refer to the WTO Agreement on Agriculture. The legal text is accessible via; https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886010/DRAFT_UK-EU_Comprehensive_Free_Trade_Agreement.pdf

Whilst it is useful to get sight of the UK’s proposed legal text, this should be very much seen as a negotiating position. The situation is likely to evolve significantly as discussions progress with the EU in the coming weeks.

NI-IRL Protocol

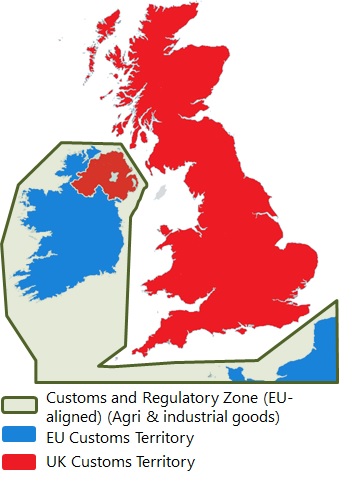

On 20th May, the UK Government set-out its proposed approach on implementing NI-IRL Protocol. A core focus of this document is on protecting Northern Ireland’s place within the UK Customs Territory and to minimise the scope for friction on GB-NI trade. It plans to do this by;

- Unfettered access on trade going from NI to GB: meaning that trade should continue as it does now, with no additional processes, paperwork or restrictions on such trade. The EU is unlikely to have problems with this as it is an internal UK matter. However, one area where there may be a potential issues is the EU foresees NI businesses having to implement its Customs Code and, as a result, exit summary declarations would be required on shipments leaving NI to the rest of the UK or other non-EU countries.

- Trade going from GB to NI: no tariffs will be levied on such trade if the goods remain within the UK Customs Territory (i.e. stays in NI). Only goods ultimately entering Ireland or the Rest of the EU, or have a high risk of doing so would face tariffs. Here, the EU takes a very different view and sees all goods entering into NI from GB as ‘at risk’ of moving South. It believes that where goods have tariff differentials between the UK and the EU, there is a significant risk of smuggling. It is clear that this will be one of the main areas of contention when it comes to discussions within the Joint Committee that will oversee the implementation of the Protocol.

- No new customs infrastructure in Northern Ireland: whilst acknowledging that there would be some additional processes and documentation for goods, particularly agri-food, arriving into NI, these would be ‘de-dramatised’ as much as possible and no new physical customs infrastructure would be built. That said, there would be some expansion of additional entry points for agri-food goods to provide for proportionate controls. This will be another issue to watch, but the UK Government’s proposals appear to give it some wriggle-room to expand existing infrastructure to manage arrangements. There are still many challenges here concerning agri-food as these will be the most arduous controls to manage, but the UK has made some progress in recruiting additional veterinarians for example.

- Northern Ireland benefits from UK trade deals with third countries: sets out the ambition for NI businesses to benefit from lower tariffs associated with any such deals, just as GB businesses would. What NI businesses can eventually avail of will also be contingent on the specific arrangements that third countries who strike FTAs with the UK are comfortable with.

Another point to note is that the UK appears to be placing a greater emphasis on using the Joint Committee to oversee the implementation of the NI-IRL Protocol as a negotiating forum, whereas the EU sees it as a body to implement what has already been negotiated. The issues above will no doubt be opened up for debate at the Joint Committee’s next meeting in early June. Further detail on the UK’s approach is available via: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uks-approach-to-the-northern-ireland-protocol

Overall, there is a sense that momentum is building ahead of the next European Council (18-19th June) which will have a key role in any decision to extend the Transition Period beyond December 2020 (decision is due by 30th June), or to provide an alternative ‘fudge’ which extends the negotiating period until October possibly. Whilst the UK is adamant that it will not extend the Transition beyond 31st December, influential voices are calling for an extended implementation period of 6-9 months beyond June 2020. They claim that this would allow businesses to make the legal changes necessary to implement what has been agreed during the negotiating phase (taking place during the transition). Whether all of this can be agreed and implemented within an additional 6-9 months remains a tall order, but any additional time would be welcomed by most businesses currently having to grapple with the Covid crisis.