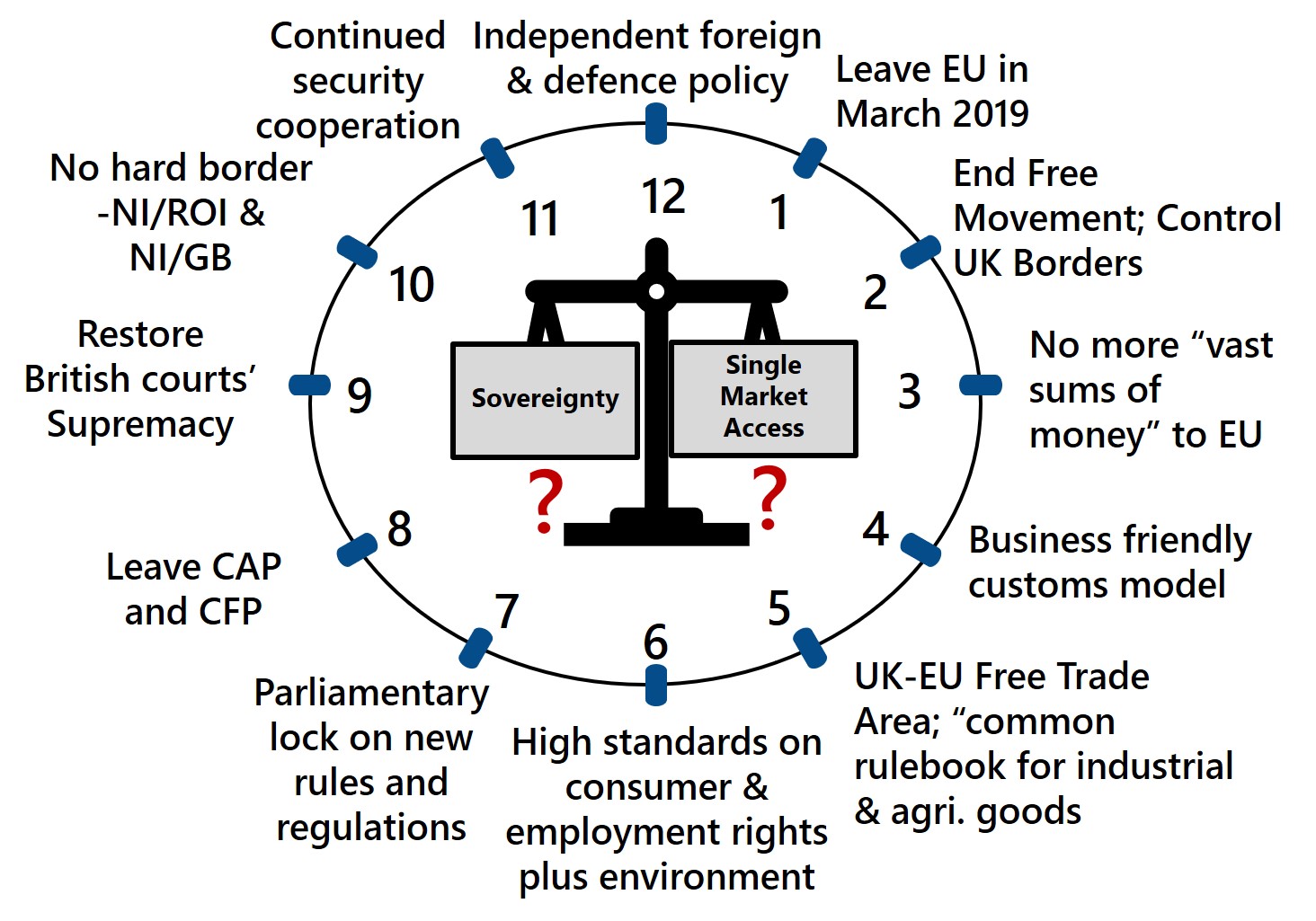

On Friday 6th July, the Cabinet finally appeared to reach agreement on its negotiating proposals for the future trading relationship between the UK and the EU. These proposals are based on 12 key principles (see graphic below) which the Prime Minister had hoped would provide “a precise, responsible and credible basis” for progressing the negotiations. It could be summarised that these proposals amount to ‘Norway plus’ for goods (including agri-food) and ‘Canada plus’ for services.

Chequers’ Proposals – 12 Key Principles

Some of the key points of relevance to agri-food include;

- Free trade area for goods – seeks to avoid friction at the border, particularly between Northern Ireland and Ireland where agri-food accounts for almost half of total goods trade. For UK agriculture, this is positive as it would help safeguard key export markets in the EU.

- Facilitated customs arrangement – seeks to remove needs for customs checks and controls between the UK and the EU “as if a combined customs territory”. The UK would apply the EU Common External Tariff (CET) for goods destined for the EU-27 with the UK controlling its own tariffs so that it can have an independent trade policy. Notably, this would become operational in stages as both sides complete the necessary preparations. This effectively combines the customs partnership and ‘max-fac’ proposals of last year but is realistic to acknowledge that the infrastructure to do this is several years away. There are concerns around what this would mean for agricultural trade as it will be very difficult for the UK to complete trade deals with other countries without having some increased access for agri-food goods. The EU will be keen to minimise such scope as this would dilute what is a key export market for Irish, French, Dutch and Danish farmers particularly.

- Common rulebook for all goods including agri-food – committing by treaty to ongoing harmonisation with EU rules on goods, covering only those necessary to provide frictionless trade at the border. Following on from previous point, this would have to include agricultural goods meaning that for UK agricultural produce that is traded with the EU-27, EU rules would hold sway. Some could interpret this as offering scope for divergence to emerge for agricultural produce that is not traded with the EU. But this would be a minefield. The capability to effectively manage dual standards in a manner that would satisfy consumer concerns and both EU and non-EU food inspectors is simply not available and would take years to establish.

- Parliamentary oversight – for incorporation of EU rules into the UK statute with the ability to choose not to do so, recognising that there would be consequences to this. T his likely to cause concern to the EU who will be keen to ensure that potential future uncertainty if Westminster decided not to pass a given EU regulation is minimised.

- State aid and competition – UK commitment to apply the common rulebook in these contexts would set limits on which agricultural policy tools the UK could adapt in the future. For instance, tax deposit schemes such as the Australian Farm Management Deposit Scheme do not comply with EU state aid rules.

- Maintain high regulatory standards – including in terms of consumer and employee rights as well as the environment. This would mean a continuation of the standards currently in place which once again should help safeguard the UK agricultural industry from third country competition. A strong environmental focus is already being pursued vigorously by the Defra Secretary.

- Northern Ireland – the Government believes that these proposals meets its commitments relating to Northern Ireland and Ireland whilst maintaining the constitutional and economic integrity of the UK but would obviate the need for the ‘backstop’ solution envisaged by the EU (i.e. NI remaining part of the EU customs territory) to be brought into effect.

- Leaving the Common Agricultural Policy – enabling the UK to pursue a domestic agricultural policy which would work in the best interests of the UK. Here, some questions remain over how a level playing field would be upheld in Northern Ireland where its farmers would be competing directly with Irish farmers still operating under the CAP. Potentially, the EU Commission’s proposals offering Member States added flexibility in developing national strategic plans in combination with similar flexibility (and funding) at a devolved level for Northern Ireland could minimise any potential policy gaps which could open-up.

The proposals seek to strike a delicate balancing act between Single Market access on the one hand and UK sovereignty on the other. Of course, the EU has yet to formally respond but the initial signs are that they will be taken seriously by Brussels as a basis for substantive negotiations on the future UK-EU relationship. As mentioned previously, it is high-time for the London-Brussels negotiations to take centre stage (despite this morning’s event covered by an accompanying article) as both parties have a duty to minimise the immense uncertainties which have emerged for both UK and EU citizens.

The UK Government plans to publish its White Paper setting-out the detail underpinning these proposals later this week.