The recently published Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) report calls for a radical shift in UK migration policy in a post-Brexit world. Its findings could have major implications for UK agri-food if implemented. Its key recommendations are listed below with some additional observations in italics;

- Focus on high-skilled workers: the UK should adopt the general principle for migration policy that it should be easier for higher-skilled workers to migrate to the UK than lower-skilled workers. This potentially exposes the agri-food sector to the risk of significant shortfalls in labour as a substantial proportion of businesses rely heavily on migrant labour to fill operative positions. Since Sterling’s decline from mid-2016, companies have been experiencing increased problems in sourcing labour. A move towards focusing on higher-skilled positions will make this challenge more pronounced for food and farming companies.

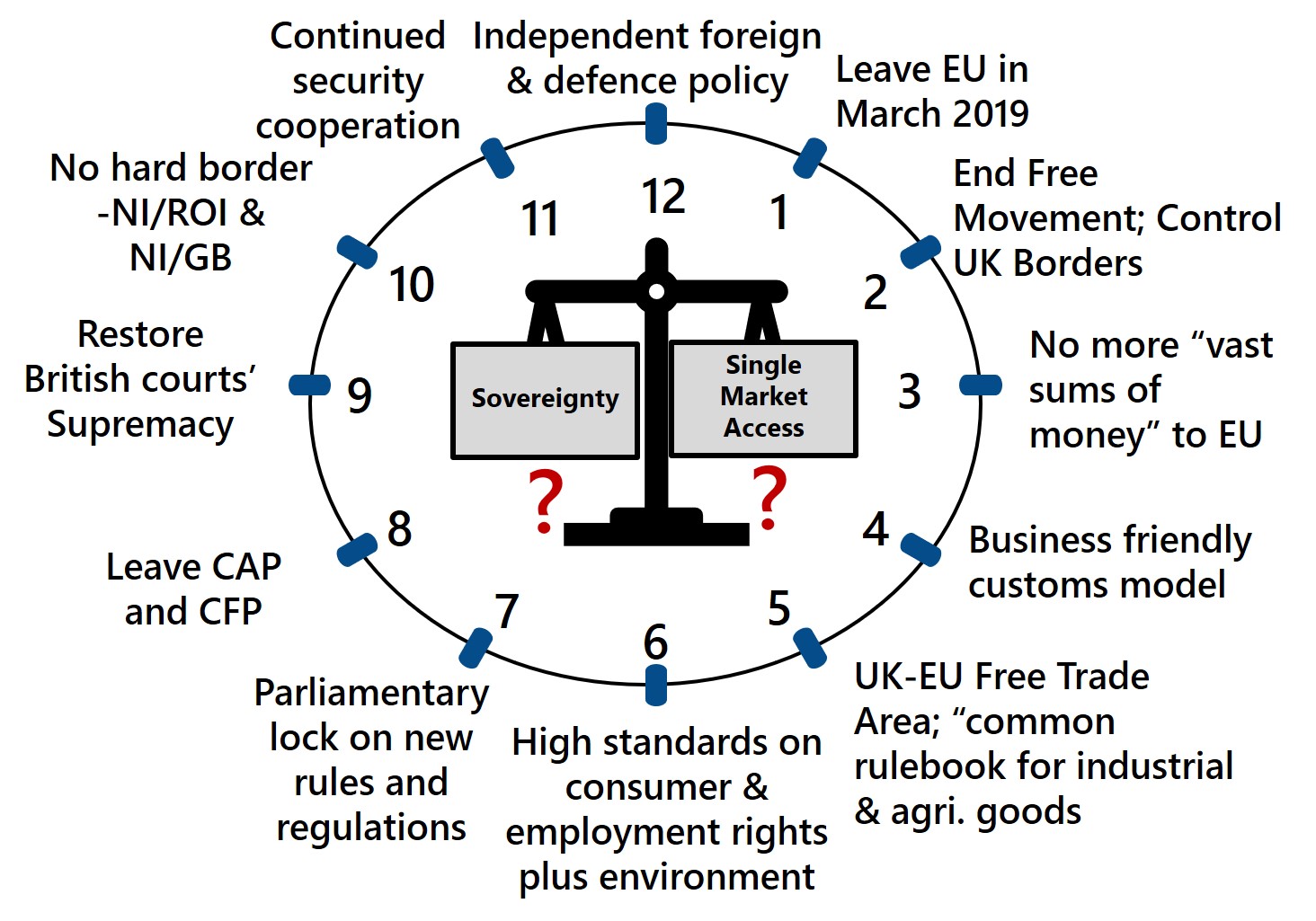

- No preference for EU/EEA migrants: this is based on the assumption that UK immigration policy is not included in the agreement with the EU. This is an arguably unrealistic assumption given how important free-movement is to the EU and the UK’s desire to retain strong access to the Single Market. Whilst it is perhaps understandable for the MAC to avoid getting embroiled in the current political debate, a report on future migration policy should at least consider a range of future scenarios, one of which is some form of linkage to the EU/EEA as enhanced Single Market access will almost inevitably come with conditions attached. Note that the EEA is the European Economic Area and includes Norway and Iceland in addition to the EU-28.

- Abolish the cap on the number of Tier 2 (highly skilled) migrants allowed into the UK: following on from the previous point, this scheme would be equally available to non-EU and EU/EEA migrants.

- Tier 2 migration open to medium-skilled workers: this makes Tier 2 applications possible for all jobs from RQF 3 or above (RQF ‘ranks’ the skill level). This means that some more medium skilled jobs (including some professional trades) would be potentially included. In conjunction with this, the MAC also states that the Shortage Occupation List (SOL) will be reviewed in its next report in response to the SOL Commission.

- Salary thresholds: maintain existing threshold (£30,000) for all Tier 2 migrants. It also argues against having regional salary thresholds. When considering the average wage rates for manual/operative positions in agri-food, this threshold is prohibitive.

- Immigration skills charge: currently set at £1,000 for most employers. This should be retained but reviewed.

- Resident Labour Market Test: this is the requirement to advertise a job vacancy locally before employing migrant labour. The MAC suggests consideration should be given to abolishing the test. If it is not abolished, then it advocates extending the numbers of migrants who are exempt through lowering the salary required for exemption.

- Sponsor licensing system: review how the current system works for small and medium-sized businesses. Any moves to decrease the bureaucratic burden required would be welcomed by most businesses.

- Consult: engage more systematically with users of the visa system to ensure it works as smoothly as possible.

- Avoid Sector-Based Schemes: the MAC states these should be avoided for lower skilled workers, with the potential exception of a Seasonal Agricultural Workers scheme. Whilst some might view it as a positive that the MAC is arguing for a special status for agriculture, most industry professionals believe that a seasonal scheme is simply insufficient for the wider agri-food sector, particularly in year-round operations within the processing sector. Without labour to process its produce, UK agriculture will struggle to find markets for its outputs. It is important that this point is made strongly to Government as it appears that the MAC has given insufficient consideration to the wider agri-food industry which relies heavily on migrant labour and has severely struggled to meet its labour needs via indigenous workers.

- Encourage agricultural productivity: by ensuring upward pressure on wages via an agricultural minimum wage if the SAWS is to be reintroduced. There is a general consensus in the industry that productivity needs to be increased. But it is not just a question of raising wages, it also concerns issues such as good broadband connectivity, modern transportation infrastructure and better training. It therefore needs a holistic approach from Government working in close collaboration with industry. Focusing on wages alone will not make the UK workforce more productive and could end up generating poorer value for money if not managed properly.

- Addressing low-skilled labour gaps: calls for extending Tier 5 Youth Mobility Scheme to meet this need. It is important to point out here that whilst the UK Government may consider some tasks (e.g. fruit picking, meat deboning etc.) to be ‘low-skilled’), they do require specialist skills which sometimes can take several years to develop. By focusing on youth only, there is a danger that UK businesses will miss out on such expertise. The focus should surely be on securing the best workers possible for the task at hand that is not available indigenously, no matter what their age is or where they come from.

- Monitor and evaluate the impact of migration policies.

- Local level impacts: pay more attention to managing the consequences of migration at local community level. This is crucial and has arguably been overlooked by policy-makers in the past decade or so. In some areas, the influx of migrants coupled with austerity has exerted severe pressure on health and education services. In future, if migration has a more pronounced impact on a given region, then it should be eligible for top-up funds to help cope with the additional burden placed on public services so that the indigenous population does not lose out.

On Northern Ireland, the MAC report acknowledged that there are unique circumstances and complexities as a result of its land border with the Irish Republic and that the agri-food sector is particularly exposed. However, it does not look favourably on advocating a separate migration scheme for Northern Ireland, nor a UK-wide scheme to deal with agri-food issues (with the exception of seasonal workers) as outlined above. In this regard, the MAC is potentially concerned that Northern Ireland would be used as a precedent for the whole of the UK or for other devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales to have their own separate policies. Given the politics at play in Westminster, it is likely that the DUP will have an influential role in all of this and are likely to push for a NI-specific scheme on fears that NI agri-food businesses could lose-out to companies south of the border.

The MAC report is seen as an important milestone for the UK in setting its own migration policy post-Brexit. It is perhaps unsurprising that given a topic as emotive and important as migration that the report’s publication has been met with a broad mixture of views from across the UK generally, but the response from the agri-food sector generally has been lukewarm. The report is available to download via: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/740991/Final_EEA_report_to_go_to_WEB.PDF