As has seemed to be the case for several months now, the Brexit negotiations are at a crucial stage and, although the EU side believes that 95% of the text for the trade deal has been agreed, three stubborn sticking points remain. These are the so-called level playing field provisions, State Aid and fisheries. Given that several deadlines have now passed and the Transition Period will end on 31st December, time is now the biggest threat.

Addressing The Remaining Issues

Of the three outstanding issues, the level playing field is deemed to be the most problematic. On one side, the EU is adamant that the integrity of its Single Market and its competitive position must be protected. It wants an agreed set of baseline environmental, climate change and labour protection standards to be agreed between the UK and the EU, which would evolve over time. The EU is pushing for the right to swift retaliatory action if the UK seeks to diverge from these. The UK, on the other hand, is resisting such moves as it sees its sovereign right to diverge as one of the key gains from Brexit. The UK also wants as much flexibility as possible on these issues to have greater leverage in agreeing trade deals with other countries from 2021. This is particularly the case for agri-food. Food standards were once closely linked to the level playing field requirements, but they tend not to be mentioned recently – a tacit acknowledgement by the EU that the UK could diverge in this area in future. However, that will come at a price in terms of Single Market access for UK agri-food producers.

Well-connected sources believe that if the level playing field issues can be overcome, that will be the key to unblocking the impasse. This because progress has been made on State Aid recently and areas such as aviation, energy, road haulage and rules of origin have not been finalised only becuase they are linked to the level playing field issue. That would leave fisheries, which is likely to come down to a last minute trade-off at a political level involving the Prime Minister, the President of the EU Commission and EU Member State leaders, most notably Emmanuel Macron.

Time Constraints

Although there are signs that both sides are inching towards a deal, it increasingly looks like whatever will be agreed between the UK and the EU will be a bare-bones agreement. As previous articles have noted, this should mean zero-tariff and zero-quota free trade in agri-food goods but non-tariff measures (NTMs) will be significant. Taking beef and sheep meat for instance, this would mean physical check rates of 15% at border control posts. To date, the default check rates for such products has been 20% (i.e. for countries trading with the EU on a Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) basis).

On 24th November, the French Customs Authorities tested their customs and Border Control Post facilities in Calais and it caused severe queues in Kent. This indicates that in the first weeks and months of 2021, there will be significant delays at the border. Concerningly, the UK authorities have not yet begun testing their arrangements, because in many cases the infrastructure and systems are not in place yet! The fact that the French are testing indicates that they are close to being ready. There is unease that from January the delays on the UK side will be even more substantial. All of this gives rise to the prospect of significant value deterioration on UK agri-food exports to the EU as time delays erode shelf-life. It could also mean the loss of high-value export sales, particularly in the retailing sector.

On the imports’ side, the UK is phasing in the introduction of its Border Controls over six months in 2021. This should help imports of highly perishable agri-food products (with the exception of some high-risk categories) from the EU. However, added friction is going to become a fact of life from 2021 and supply-chains are going to have to adapt sooner or later.

Time will also be an issue in terms of ratifying any trade deal, particularly on the EU side as it normally requires a vote at the European Parliament. The last session of the European Parliament is currently scheduled for 14th December, however, there have been suggestions that MEPs have been advised to keep the 28th December available. Another option being mooted by the EU is to “provisionally apply” any UK-EU trade deal from 1st January with the ratification process at EU Parliament and potentially at Member State level (if the deal includes areas solely within the remit of each Member State). Either way, the EU Council scheduled for 10th-11th December will be crucial and it is thought that a deal will need to have been agreed by that point and the process of translating the deal into legal text and other EU languages will need to be well underway.

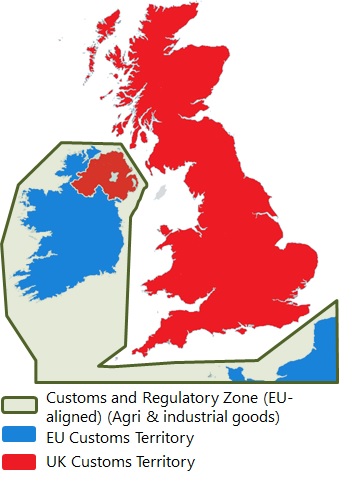

If a trade agreement can be reached between the UK and the EU, any initial agreement can be improved over time as is the case with trade deals elsewhere. That said, the prospect of a No Trade Deal remains significant. If a Deal is reached, there are many technical issues, including transit arrangements in the UK and Ireland, which have not had any time devoted to them, and will need to be ironed out from January. Although it is inevitable that elements of a phasing-in period will need to be implemented by both sides (e.g. Belgian customs authorities have acknowledged that some of its customs requirements will be relaxed initially), businesses need to brace themselves for significant change from January.