On 14th November, after ‘thousands’ of hours of negotiations, the UK and the EU finally reached an accord over the text on the Irish border enabling them to publish the draft Withdrawal Agreement. Within hours of its publication, this 585-page legal document (see link below) led to the resignation of two Cabinet Ministers and at one stage, there were even rumours that Michael Gove would resign, having reportedly turned down the offer of becoming Brexit Secretary. This would have added yet more uncertainty for the UK agri-food industry, particularly in the context of future agricultural policy, but at least the Defra Secretary is staying put for now.

The UK Government’s Chequers proposal (see August Bulletin) has been amended in some key areas. The idea that, after the Transition period, a technology-based ‘Facilitated Customs Arrangement’ would be put in place to allow seamless trade was rejected by the EU. Instead the UK will have to remain in a Customs Union with the EU until alternative arrangements are put in place that are acceptable to both sides. There will be a review in July 2020 and if the EU is not satisfied, then the Transition Period will be extended. This can only be done once, and the UK Government has stated that it should not be extended beyond 20222 (the date of the next General Election).

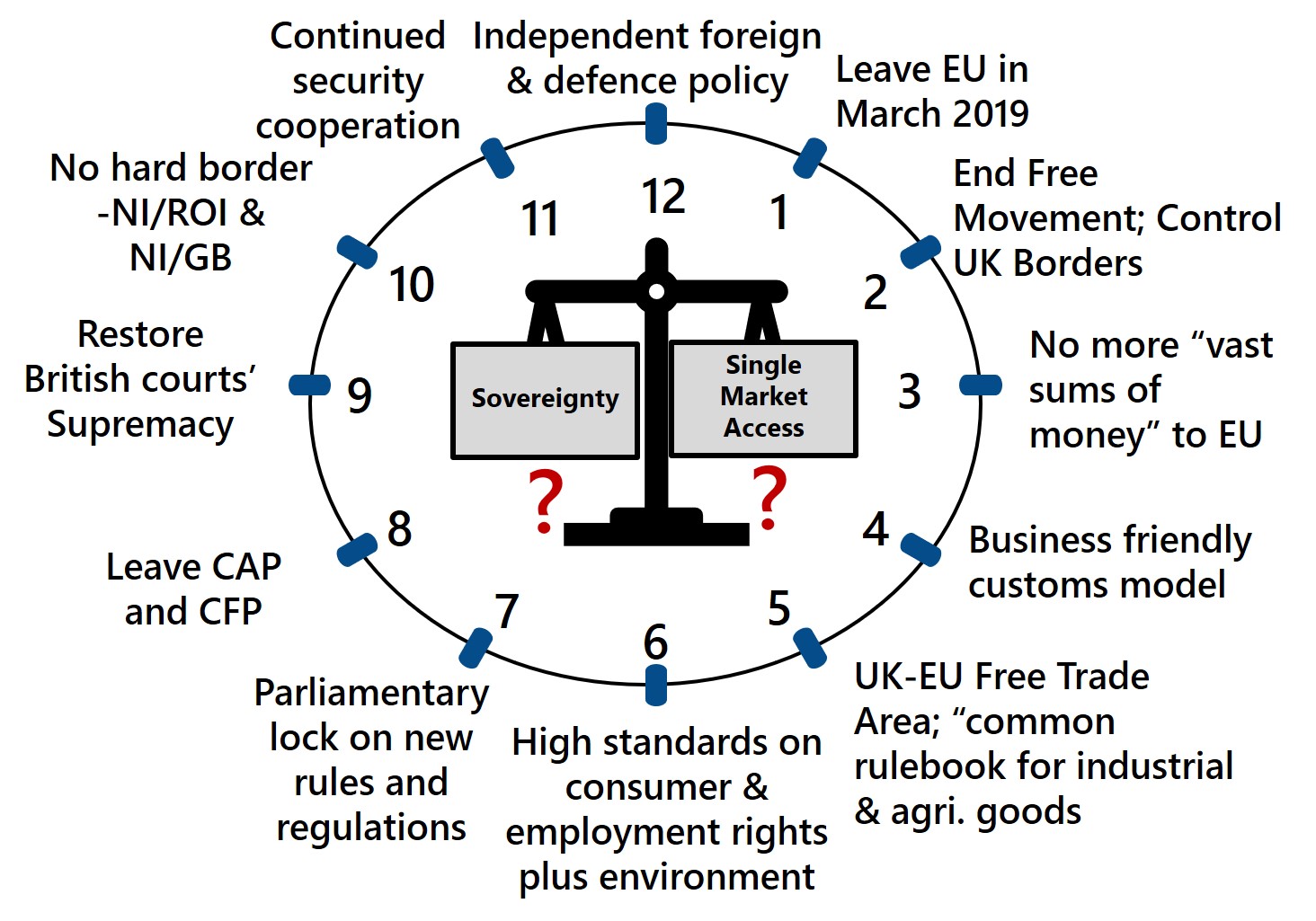

The key points of the Withdrawal Agreement include;

- Backstop via a Customs Union – This is to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland. It will be achieved by a UK-EU Customs Union (Single Customs Territory) which will avoid the need for customs checks on the Irish Sea. This Single Customs Territory will be temporary but will apply “unless and until” a mutually-agreed new trading arrangement between the UK and the EU is introduced which, itself, avoids the need for a hard border on the island of Ireland. However, using a swimming-pool analogy, under this Customs Union arrangement, Great Britain (GB) would be at the shallower end whilst Northern Ireland would be at the deeper end, applying the full “Union Customs Code” and essentially remaining fully aligned with both the Single Market and the Customs Union. To ensure a level playing field, the UK commits to following EU competition rules (including State Aid) and to keeping some existing laws on labour, environment and taxation. From an agri-food perspective, this would mean that potential policy tools such as deferred taxation arrangements as used in Australia would not be permissible. Free movement of labour would also end so there would be additional regulatory steps that would need to be adhered to when recruiting from the EU, although visas for short trips would be easily obtainable. With respect to agri-food trade the following points are also noteworthy;

- Checks on GB to NI agri-food trade such as live animals (which already takes place today) and products of animal origin would take place on a limited basis. Some commentators believe that this will involve an online transit declaration which could be submitted in advance of a shipment via a back-office, as well as risk-based checks of goods upon arrival at the destination. However, these provisions have yet to be confirmed.

- The UK-EU Customs Union would avoid the need for tariffs, quotas and rules of origin on UK-EU trade.

- Financial Settlement – as previously indicated, the UK would honour all its financial commitments so that there would be no shortfall in the current EU budget as a result of Brexit. This figure is estimated to be in the region of £39 billion, but some estimates from the National Audit Office indicate that the eventual figure could surpass £50 billion, as some payments (e.g. pensions) could continue to 2064. However, most contributions would be complete by 2025.

- Citizens’ Rights – existing residence and social security rights would be maintained for the 3 million EU citizens living in the UK and the 1 million British citizens living in the EU. EU nationals will also be permitted to claim permanent residence in the UK and most family reunion rights would also continue. Any legal issues would have to pay due regard to the European Court of Justice. This will at least give some certainty to many agri-food workers from the EU working in British agriculture, but getting access to new workers remains a major issue.

- Transition Period – as previously outlined, there would be a transition period (aka implementation period) until the end of 2020. But this can be extended for a specified one-off period, subject to mutual agreement. During the transition, the UK would continue to apply EU regulations in full but would no longer have a formal say or influence on the setting of these regulations. If the transition extends beyond 2020, then additional UK payments to the EU budget are likely. This has prompted much talk of ‘vassalage’ from hard-line Brexiteers.

- Governance – this will be administered via a complex set of arrangements drawing upon dispute resolution mechanisms (similar to the EU’s association agreement with the Ukraine), provisions to ensure that the ECJ has the final say on EU’s laws, and independent arbitration to resolve relevant treaty disputes.

The full version of the report is accessible via: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/draft_withdrawal_agreement_0.pdf

Whilst the agreement has been approved by the UK Cabinet, it has led to a series of Ministerial resignations including the Brexit Secretary as alluded to above. For an agreement such as this, there were always going to be difficult compromises, particularly considering the UK’s relatively weak bargaining power in the process. It should be remembered that the UK’s population is 66 million versus 450 million in the rest of the EU; the EU’s economy is nearly six-times larger than the UK, and the UK’s exports to the EU are estimated at 13% of its GDP, whilst the EU’s exports to the UK are equivalent to 3% of its GDP. Nevertheless, although the Article 50 process is heavily weighed in the EU’s favour, it can be argued that the UK has not played its hand particularly well – for example, by invoking Article 50 before it had worked out its negotiating position

Whilst the Deal is undoubtedly unsatisfactory to some (many?), it is certainly better than a No Deal scenario for the agri-food sector. However, there is considerable doubt as to whether the agreement will ever be enacted, as Teresa May will have significant difficulties getting it through Parliament. Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish Nationalists and the DUP have already indicated they would vote against the deal as it stands. A sizeable portion of the Conservative party is also unlikely to back it. The Prime Minister seems to have little room for manoeuvre. Neither the DUP nor the European Research Group of Conservative Brexiteers are willing to cede any further ground and are more likely to call for the Prime Minister’s resignation. Arch-Remainers are unlikely to move either, although the Government might be able to sway some Labour MPs to vote for the Deal. However, this is still unlikely to be sufficient and will likely necessitate some form of concession to milder-Remainers who might be persuaded to vote for the Deal if there is an option to change course at a later stage (i.e. during the Transition, including the option to re-join the EU). But all of this is just speculation at this point and it is very difficult to see how the next few days will pan out, let alone the next few months.

All the while, the EU-27 are showing a relatively united front and are making arrangements to hold a special EU summit on 25th November so that Member States can formally agree the deal which would then be subject to votes in both the European and Westminster Parliaments. Many more twists and turns lay ahead.