On 20th June, details were released of an exercise which outlined the scale of the areas of north-south cooperation on the island of Ireland which could be affected by Brexit. This exercise informed the UK-EU negotiations which led to the emergence of the Irish backstop. It shows that there are 142 areas of cross-border cooperation encompassing healthcare, policing, the environment and, of course, agri-food.

Nearly 30 of these areas of cooperation (20%) have direct linkages to agriculture whilst a further 17 are linked to water, waste and the environment. Areas relating to agriculture and food include;

- Food safety: linked with the application of EU Regulation 178/2002 on General Food Law.

- Trade: appears in various guises, whether related to North-South trade promotion (via InterTradeIreland) or the management of cross-border trade with respect to the joint management of customs, transit of goods, mutual recognition of authorised economic operators (AEOs) etc. It also includes collaboration on promoting dairy trade.

- Common Agricultural Policy: discussion around policy choices and implementation issues which are faced by both jurisdictions on the island of Ireland. It does not involve policy formulation.

- Rural Development: EU LEADER cooperation including the facilitation of application for funding for collaboration projects including landscape management.

- Plant health and associated regulatory checks for quarantine pests: a working sub-group oversees cooperation on plant health, pesticide and bee health issues and joint actions delivered through a joint work programme. This area has linkages to external border controls (documentary checks, identity checks etc.) relating to external trade in these products.

- Collaboration on regulatory checks on live animals and products of animal origin: cooperation encompasses information exchange on consignment movements and trade as well as discussions on topics of mutual interest including the registration of traders and the use of the Trade Control and Expert System (TRACES) which controls the import and export of live animals and animal products in the EU. This area is seen as crucial towards avoiding a hard border.

- Animal health, welfare and disease control: includes collaboration initiatives on Tuberculosis (TB) and Brucellosis, veterinary medicines regulation and trade as well as animal transport.

- Equine industry collaboration: covering cross-border movements and strategy development for the Irish equine sector.

- Academic partnerships in agri-food: encompasses a variety of partnerships to promote cross-border initiatives including access to research funding as well as programmes to provide a range of higher and further education courses in agriculture.

- Farm Safety: initiatives to jointly manage issues across the island.

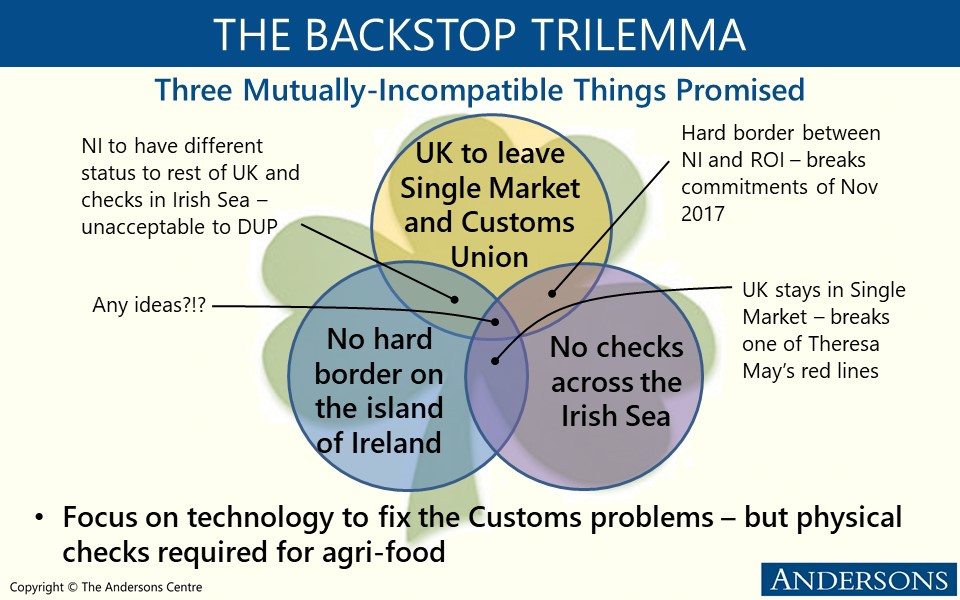

Overall, the information released by the EU Commission and DExEU reveal the extent to which north-south collaboration has evolved over the past 21 years since the Good Friday Agreement. Tellingly, many of the 142 collaboration areas go well beyond the technical and fiscal aspects of customs and single market regulation and it is implied that technology alone will not be able to solve all of the challenges posed by the Irish backstop trilemma. Undoubtedly, the continued operation of the Common Travel Area facilitating the free movement of people across the island of Ireland and the UK will be a crucial component of tackling the issue. However, there are many unanswered questions in other areas, particularly the regulation of agri-food trade which the UK Government will need to address.

To this end, DExEU have also announced the establishment of a Technical Alternative Arrangements Advisory Group to explore alternatives to replace the Irish backstop by the end of 2020. The group will be co-chaired by the Brexit Secretary, Steve Barclay, and Jesse Norman (Financial Secretary to the Treasury) and includes several Northern Ireland-based members (e.g. Declan Billington, Michael Bell and Dr. Katy Hayward) who have been to the forefront of tackling Brexit challenges, particularly from an agri-food perspective. Having such Northern Irish involvement should hopefully lead to more realistic proposals on how to obviate the need for a Backstop in comparison with previous initiatives which have repeatedly come up short in terms of understanding and addressing the complexities involved.