Recently we have received a few queries regarding future farm support in England and in particular how this might affect agricultural lettings. We therefore thought it might help readers if we refreshed what we do know and also highlighted possible problem areas.

The Agricultural Bill has passed through the House of Commons and is now in the House of Lords. It is expected to become law by the end of the summer, without many amendments, particularly surrounding the future support mechanisms contained within it. The Bill, however, only sets out the Government’s ‘broad powers’, it does not give details of how the powers will be used. A consultation on how changes in support will be enacted (especially the phase-out of the BPS) is expected in the Autumn, with some commentators expecting something from Defra by September.

Agricultural Transition

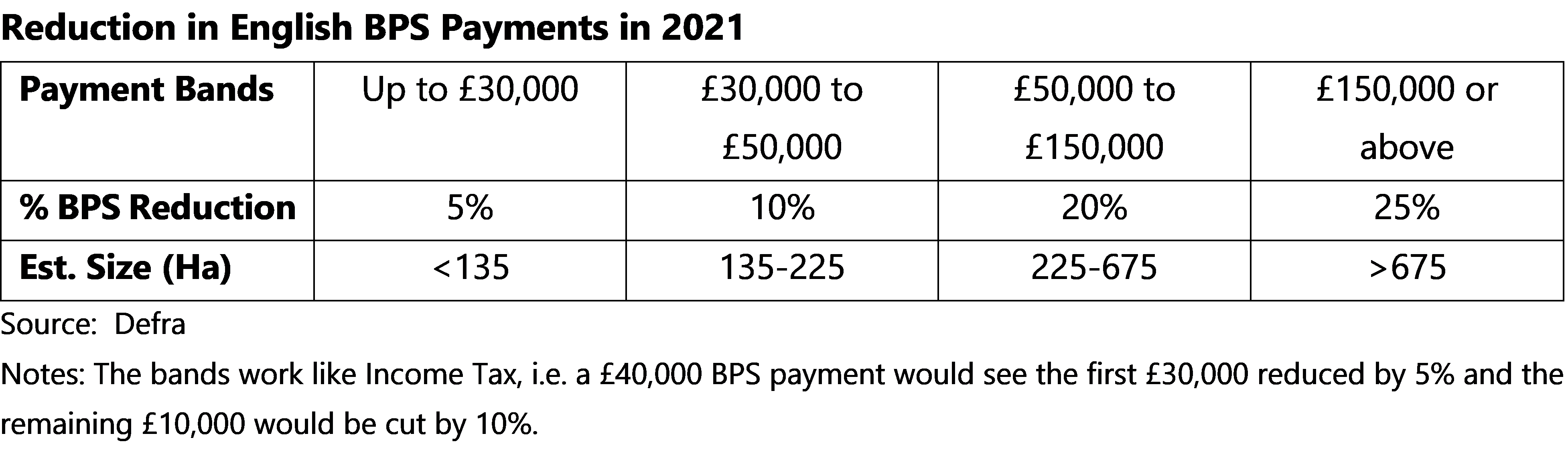

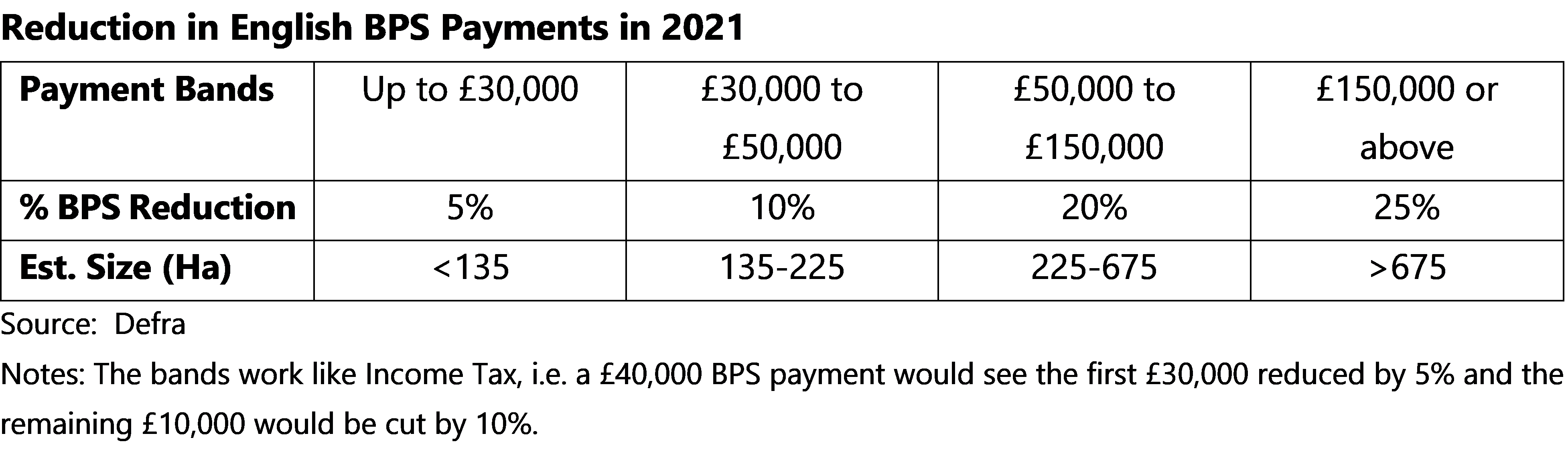

We do know direct support (the BPS) will be phased-out from 2021 to 2027 (Agricultural Transition) and replaced by the Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme, together with other schemes to help increase farm productivity, animal welfare and support for Producer Organisations. There has been quite a lot of lobbying to delay the start of the Transition by one year, but Defra appear to be resisting this and as this date is included in the Agriculture Bill it looks set to commence next year. This will mean in 2021 we expect to have a direct payment scheme similar to the current BPS but payments will be reduced as follows:

Currently we only know the deductions for 2021. It is hoped the consultation later in the year may shed some light on future % reductions. Our view is that as the ELM scheme is not due to be launched until 2024, the deductions in the first few years could be relatively slow. These could then increase more sharply as funds are redirected/required for the ELM scheme later in the Agricultural Transition.

De-Linking

This is a mechanism that breaks the link between receiving support and occupying agricultural land. Once support is de-linked a farmer could double the size of their holding, or stop farming completely – they would still get the same future stream of income tapering-off to 2027. It effectively gives the claiming business a right to the future support. The key point is that it will be based on what the claimant received in a ‘reference year’ (or years). The reference year is not yet known and this will determine who gets the support through to 2027.

De-linking will definitely happen, it is written in the Agricultural Bill, but it cannot happen before the 2022 claim year. So we are expecting the 2021 scheme structure to be similar (or the same) as the 2020 scheme year with entitlements, which presumably can be traded.

The closer the reference year is to de-linking the less ‘problems’ there will be due to changes in business structures or land occupation. It would therefore seem logical for it to be 2021, but earlier dates or even a range of dates is possible. The EU has usually used a date before any announcement has been made so that people cannot ‘profit’ from the system. There is likely to be force majeure and business change provisions similar to those which operated when the Basic Payment was introduced – but details of these are also unknown.

Any Tenancy Agreements written pre-2019 are unlikely to have any clauses in them which deal with de-linked payments. If a Tenant has made a BPS claim which included the reference year, the right to the future income stream would become vested in the Tenant. If the Agreement is brought to an end during the Agricultural Transition the Tenant would still have the right to receive the de-linked income stream and the land may not have any ‘support’ for the incoming Tenant. Of course the incoming Tenant may have some ‘support’ to ‘bring’ with him, and so we can already see the problems with what rent level can be asked or what price Tenant’s will be prepared to pay – every situation could be different.

Those preparing agreements this autumn will need to ensure they contain clauses to try and protect the Landlord’s position in case 2021 is the reference year, so that he/she can offer the right to receive future support along with the land for incoming Tenants. If 2019 or 2020 turns out to be the reference year then it may already be too late.

Lump-Sum

This must not be confused or ‘bundled-up’ with de-linking. It is the idea that the future stream of income from de-linked payments is rolled-up into one single payment. But it is separate from de-linking and is only an option in the Agriculture Bill; it may not be introduced in 2022, it may not be available to everyone, it may not even be introduced at all. More information is (again) expected in the upcoming consultation. The idea is that it could be used as a retirement sum or allows for investments to be made. If it is introduced, it is unlikely to be available to everyone at the same time, as there just wouldn’t be enough budget if everybody took it up! But there might be an age threshold for example. For those Agreements which come to an end within the Agricultural Transition, the Tenant could potentially leave with a de-linked lump-sum.

Environmental Land Management

Once the BPS has been phased out, the main support for farmers will be the Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme. But in a Landlord and Tenant situation or Contract Farming Agreement how is it going to be dealt with? This looks like an area where they’ll have to be a lot of ‘sorting out’ over the next 5-10 years as a new normal gets established. It certainly does not look like it is going to be as simple as the BPS.

For AHAs and existing long-term (whole farm?) FBTs it will likely be down to the tenant to decide whether to enter or not. But the ability to pick up ELM payments will presumably be part of the earnings potential of the holding and would therefore come into consideration of the rent. This might become a contentious area in rent reviews in the future – what if the Tenant had entered into a low-level, low income, ELM agreement, but the Landlord thought that he/she should have gone for a higher-paying one and be paying more rent?

For new/short term FBTs, we might well see situations where the Landlord wants to be the claimant, both so that they are in control of what happens and so they are guaranteed the income. Of course, it depends on the detailed ELM rules – will Landlords even be able to apply if the land is let out? The land would therefore be let ‘naked’ without any support and the rent would reflect this.

Any tenancy agreement would have to bind the Tenant to adhere to the ELM requirements – as has been done in the past for ES / CS agreements etc. But this is not always the best approach, as the Tenant (the actual land manager) hasn’t got any financial stake in the ELM agreement. This might become more of an issue if the payment methods become more sophisticated over time – e.g. payment by results, reverse auctions etc. Perhaps some revenue-sharing model would be the answer – but with the Landlord still remaining the agreement holder?

There are also Contract Farming Agreements (CFAs) to consider. There has been differing opinions in the past on whether BPS has been included in the ‘pot’ or not. Often agri-environmental payments have been kept out of agreements and remain with the farmer (land provider). Will ELM payments go in the pot or not? Perhaps not – which might have an effect on first charges and divisible surpluses in some cases. But where the ELM scheme requires a sophisticated on-the-ground management, it might have to go into the agreement to get buy-in from the contractor.

Unfortunately we are posing more questions than answers, but hopefully this article highlights key areas which will need to be kept abreast of over the coming months, especially ahead of autumn lettings. The consultation in the autumn should help to answer a few questions as we adjust to the new arrangements over the next 5-10 years.