Despite most of the month being dominated by discord, it appears that the Brexit talks are at last getting down to the real detail. After the October European Council, the EU instructed its Chief Negotiator to ‘continue’ with the Brexit negotiations. However, the UK’s desire was for an ‘intensification’. As a result, it temporarily withdrew its invitation to Michel Barnier to come to London for further talks with his counterpart David Frost. Whilst this increased the chances of a No Deal, in tense talks such as this, there always comes a point where a big ‘fall-out’ occurs. Arguably, it is not until this happens, that the real negotiations start.

Landing Zone Visible

There are signs that substantive negotiations are now underway. The ‘landing zone’ between the UK’s and the EU’s position is also getting clearer. However, there are still some difficult trade-offs around the Level Playing Field and Fisheries which have hampered progress throughout 2020. Whilst the EU, and particularly coastal Member States such as France, are talking tough on Fisheries in a bid to get access to the UK’s waters as close as possible to the status-quo, it is clear that the EU will have to concede on this issue. It is also apparent that the EU is standing firm on its requirements around the Level Playing Field, particularly with respect to State Aid. Arguably here, the UK’s intent to break international law as outlined in its Internal Market Bill, has made the EU more insistent on ensuring that the UK will not be able to have good access to the EU Single Market on the one hand, and be able to undercut it on the other. That said, there are signs of movement from the EU side on this as well. The focus is now on key principles that both sides should adhere to, ensuring that the UK has a strong independent regulator which can uphold what is agreed during the Brexit negotiations.

Despite these signs of progress, the time available is very short. The EU side now believes that it will be into November before an agreement might be reached, leaving very little time for the ratification process. Given the importance of issues such as Fisheries in some regions, this could result in some difficulties in getting the vote through the European Parliament. With the Transition Period ending on 31st December, it is last minute glitches such as this, which could also result in a No Deal situation on 1st January.

Business Preparation

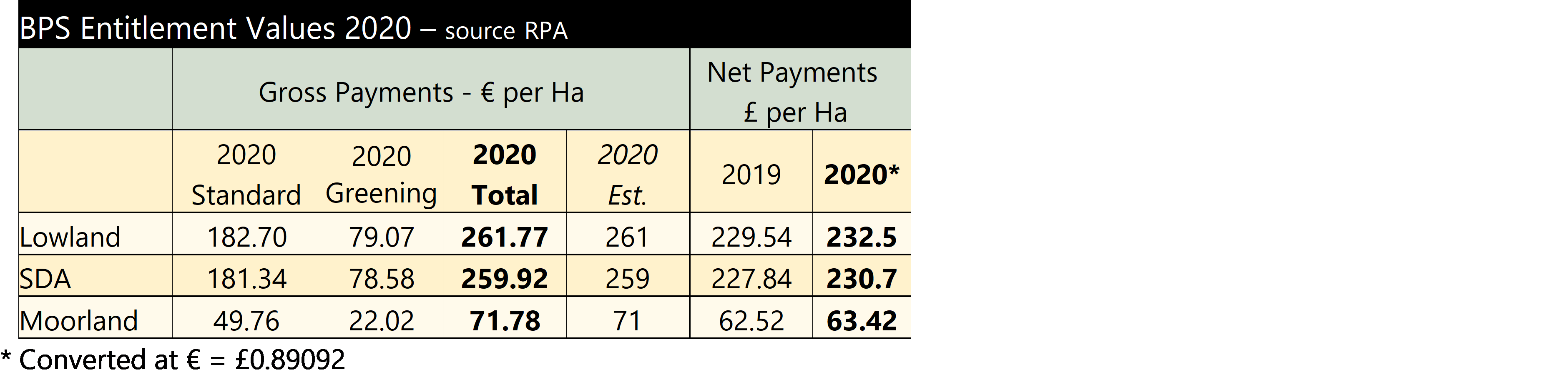

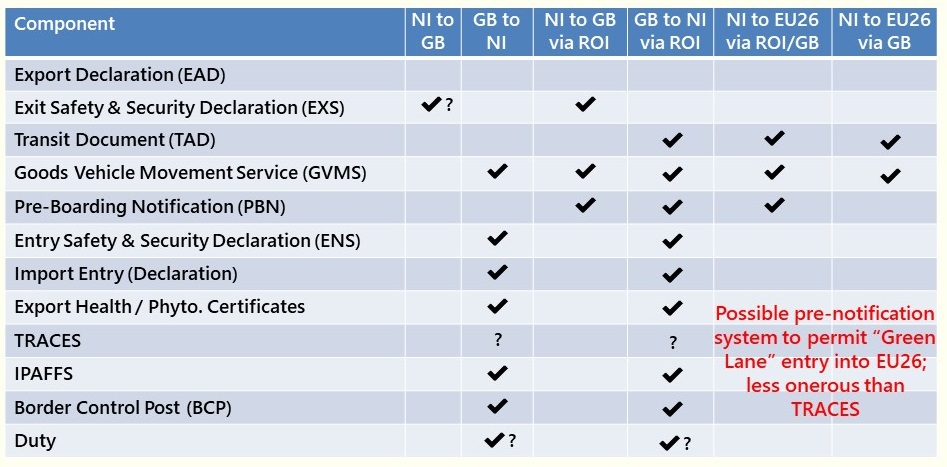

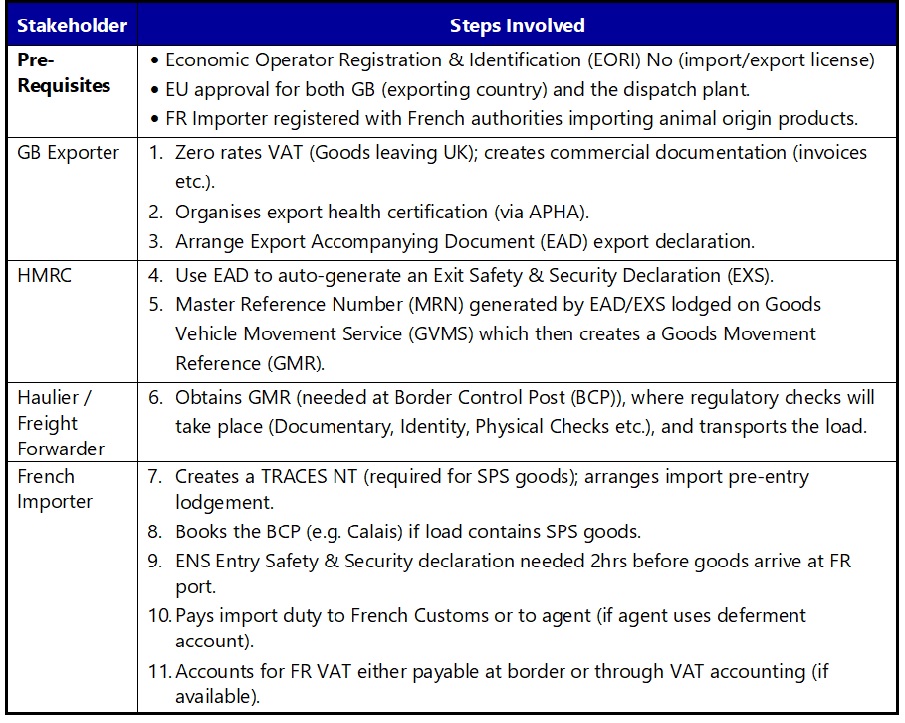

All the while, agri-food businesses are left scratching their heads as to what precisely will be expected from them when trading with the EU from January. In recent weeks, Defra has held a number of webinars which have sought to shed light on the process. This includes information on Defra’s Export Health Certification (EHC) online facility which allows exporters to apply for, manage and keep up to date on the progress of their EHC applications. What is clear is that irrespective of whether there is a Deal or not, change is coming and businesses must prepare for this, even if time is limited. In recent weeks, Andersons has been involved in examining the key regulatory processes the British businesses will need to adhere to when exporting to the EU. These are outlined, in general terms, below as specific steps can vary depending on the products/species involved.

Regulatory Steps on Agri-Food Exports from GB to France Post-Transition

Sources: Customs Clearance Consortium / Andersons

On 8th October, the UK Government published its updated Border Operating Model, following the initial publication in July. Much of what was previously announced remains in place (see July article). This version focused on additional inland border infrastructure to be constructed to manage delays at the border as well as details of a new Kent Access Permit which HGV drivers will need before being able to travel onwards to Dover for instance.

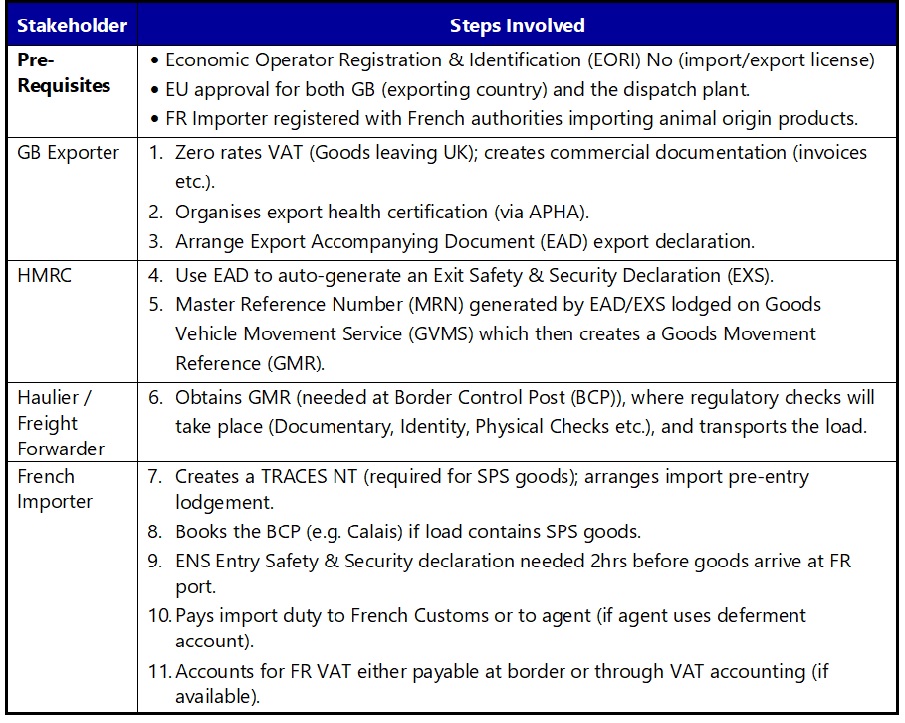

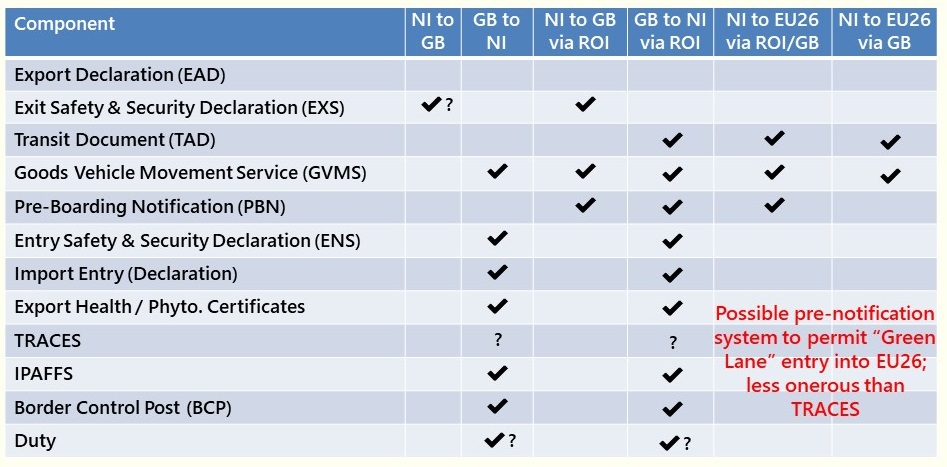

Whilst additional information is emerging in some areas on what is required post-Transition, there is very little detail on how trade with Northern Ireland will be managed. This is being discussed at the Joint Committee between the UK and the EU. Further information is expected soon. However, this is becoming increasingly urgent as the Protocol, and associated checks on GB to NI trade will need to be operational from January. Based on information to hand at the time of writing, below is an overview of documentation that will be needed for trade with NI whether transiting directly or via the Republic of Ireland. For those that trade with Northern Ireland, it is worth checking the Trader Support Service to see what support that might be available in addressing the regulatory requirements.

Overview of Documentation Needed for NI Agri-Food Trade Post-Transition

Sources: Customs Clearance Consortium / Andersons

Whether formally or informally, it is clear that an implementation period of at least six months is needed so that businesses can put in place the measures required to manage trade between the UK and the EU. With such limited time available, even if a Deal is agreed, there will be plenty of follow-up negotiations needed on numerous technical points arising from Brexit which simply cannot be addressed in the time available. In this respect, Brexit has become more of a process than a one-time event. So, Brexit-related wrangling will continue for some time yet!