On 28th February, the UK and New Zealand signed the UK-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (FTA), formalising the agreement-in-principle which was announced in October 2021 (see https://abcbooks.co.uk/uk-new-zealand-trade-deal/). The FTA is similar in nature to the UK-Australia FTA announced in December. The deal is seen by the UK Government as another important step towards joining the Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The agreement will now be laid before Parliament for scrutiny.

The key points are;

- Tariffs: upon entry into force, 100% of tariffs on UK goods exports to NZ will be removed whilst tariffs on 99.5% of goods imports into the UK from NZ will immediately be removed.

- Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs): will remain for the most sensitive product being imported into the UK including:

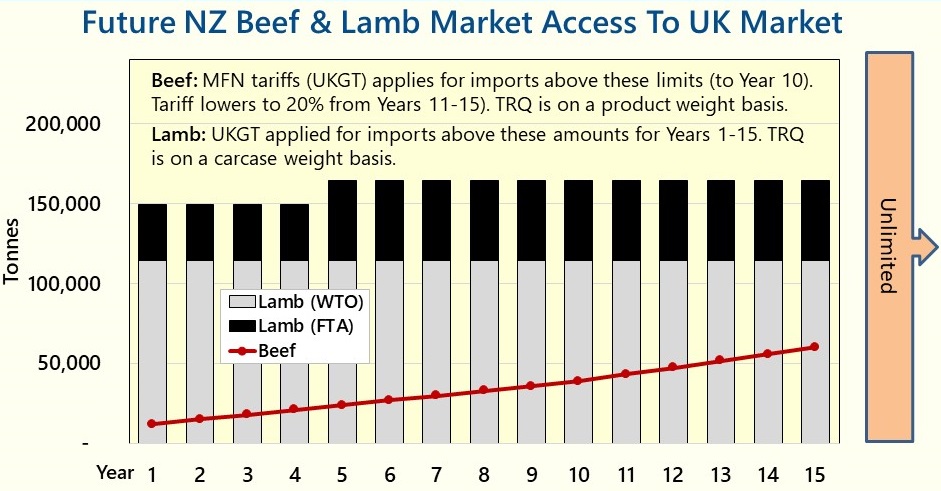

- Beef: access would be limited by tariff rate quota (TRQ) in the first 10 years. This would commence with access to a duty-free transitional quota of 12,000 tonnes in year 1, rising in equal instalments to 38,820 tonnes in year 10. Any beef imports above the annual TRQ allowance would be subject to the UK Global Tariff (UKGT). In the subsequent 5 years (year 11-15 after entry into force) a product-specific safeguard will be applied on any beef imports exceeding a further volume threshold rising in equal instalments from just over 40,000 tonnes in year 11 to 60,000 tonnes in year 15. All TRQ allowances are on a product weight basis. All tariffs would be eliminated from year 16 onwards.

- Lamb: access would operate in a similar manner to beef, although tariff-free TRQ access would be managed in a series of step-changes as opposed to annual incremental increases and the allowances are calculated on a carcase-weight basis which is somewhat more limited than a product weight basis. In years 1-5, an additional 35,000 tonnes per year could be imported tariff-free. This, of course, is in addition to the 114,000 tonnes of the WTO TRQ that New Zealand has historically had available. During years 5-15, the tariff-free access will increase to 50,000 tonnes per annum followed by unlimited access in year 16. Importantly, trade via the FTA TRQ can only commence once utilisation of the WTO TRQ has reached 90%. Any imports exceeding the FTA TRQ will be subject to the UKGT tariff rate.

- Dairy: similar structures will also operate for dairy products with unlimited access being phased in over 5 years.

- Butter: initial duty-free TRQ of 7,000 tonnes rising to 15,000 tonnes in year 5.

- Cheese: there will be an initial duty-free TRQ of 24,000 tonnes in year 1, increasing incrementally to 48,000 tonnes in year 5.

- Fresh Apples: given the seasonal nature of production in both countries, tariffs on imports into the UK from 1st January to 31st July would be eliminated as soon as the deal comes into force. Imports during August to December will be liberalised over 3 years. During this time, there will be a tariff-free TRQ of 20,000 tonnes per year. All fresh apple imports from NZ would then be tariff-free and quota-free from year 4 onwards.

Sources: UK Government and Andersons

- Customs Procedures: the deal is ambitious with respect to minimising customs procedures and the promotion of e-certification.

- Rules of Origin (RoO): are set to remain standard for agri-food – i.e. a threshold of 15% of products traded can be non-originating from the country of origin (i.e. UK or NZ) in order to gain tariff-free access. The RoO for automotive vehicles (25% originating materials as opposed to the standard 55% threshold) will become much more liberalised. This is seen as a big gain for the UK, given the extent of its integration with EU supply-chains.

- Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures: the The FTA seeks to minimise barriers in the area. Both countries are to recognise equivalence where both countries have similar standards and the deal will function in parallel with the existing UK-NZ Sanitary (Veterinary) agreement. The UK Government is also keen to emphasise that the deal “does not create any new permissions or authorisations for imports from New Zealand and does not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare, plant health, and food standards.”

- Animal Welfare: has a dedicated chapter in the agreement which includes non-regression and non-derogation clauses which the Government intends that neither country will lower its animal welfare requirements in a manner which impacts trade. There is also an ambition to work together internationally to encourage greater animal welfare standards and research cooperation on animal welfare issues.

Overall, the main thrust of the UK-NZ FTA is very similar to the previous agreement-in-principle and is quite similar to the FTA that the UK has agreed with Australia. As such, it creates another precedent for future trade deals. It is clear that the UK has offered enhanced market access for NZ agri-food suppliers in return for greater access to the NZ automotive and services sectors. The cumulative impact of these trade deals is also important. Whilst there is a 15-year transition period for beef, by year 14, the combined Australian and NZ TRQs (~214Kt) access will have surpassed recent years’ annual imports from Ireland (204Kt). That said, just because TRQ access is available, it does not mean that it will be fulfilled as Asia-Pacific will remain very important to Antipodean suppliers.

Finally, in the case of NZ, it must be acknowledged that whilst there are some differences in its standards versus the UK, its standards are very closely aligned. Something that the EU also acknowledges in its veterinary agreement with NZ. Therefore, whilst the competitive pressure will increase, the playing field is quite level in this instance. What UK farming needs needs to do is to focus much more on improving its market orientation (i.e. focus on satisfying consumer needs profitably and sustainably) and to improve its value proposition and marketing generally, both at home and abroad. That is its best chance to successfully competing with the likes of NZ in the long-term.

More information on the UK-NZ FTA is available via: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-new-zealand-free-trade-agreement