Defra has released its forecasts for Farm Business Income (FBI) for 2021/22. Taken from the English Farm Business Survey (FBS), the data shows FBI for various standard farm types. The FBS works on February/March year ends so the period being reported covers harvest 2021 and the 2021 BPS – including the first year of deductions under the Agricultural Transition. FBI can be thought of as equivalent to the ‘Net Profit’ measure widely used in accountancy. The full release can be found at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/farm-business-income/farm-business-income-in-england-202122-forecast.

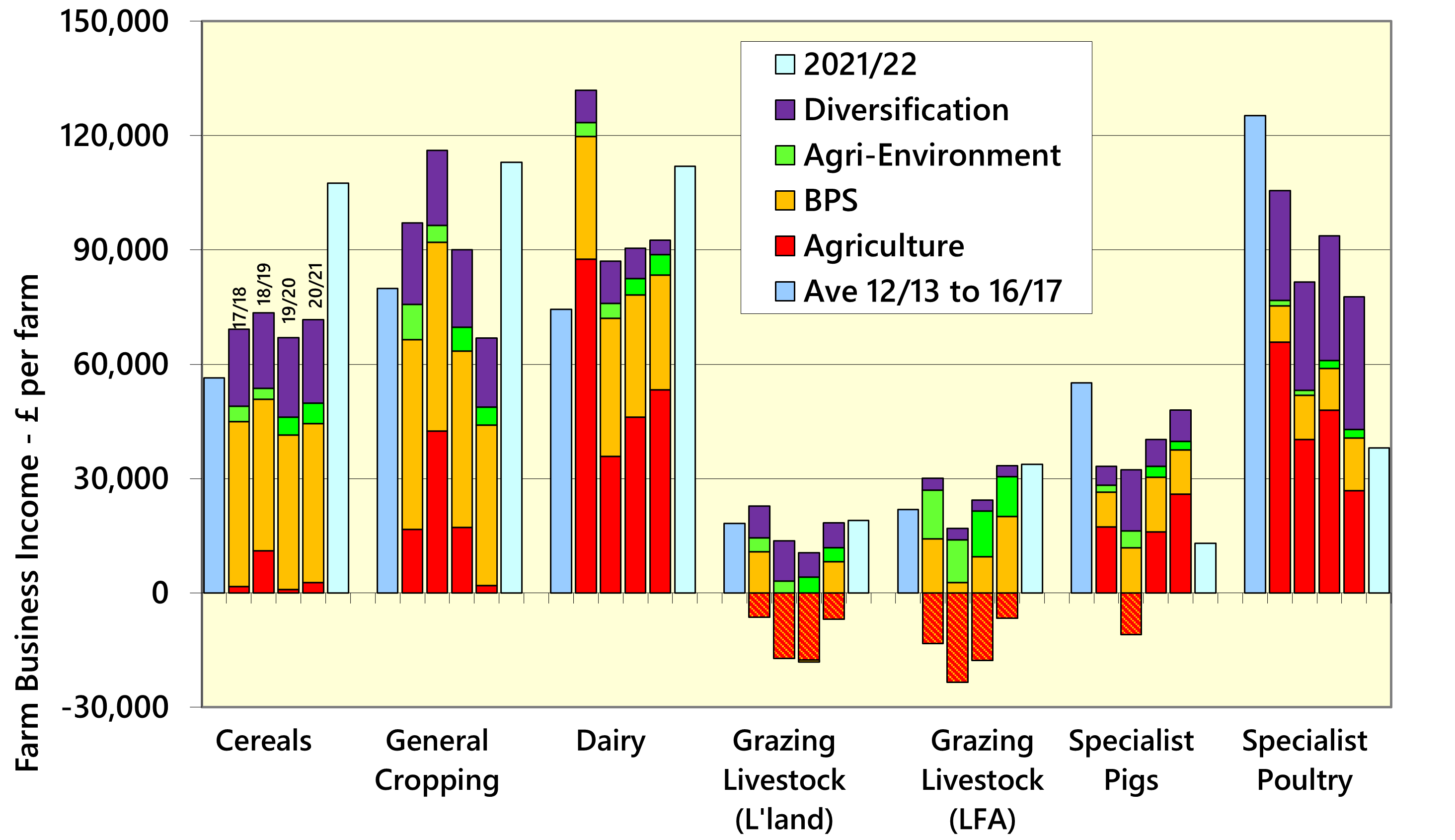

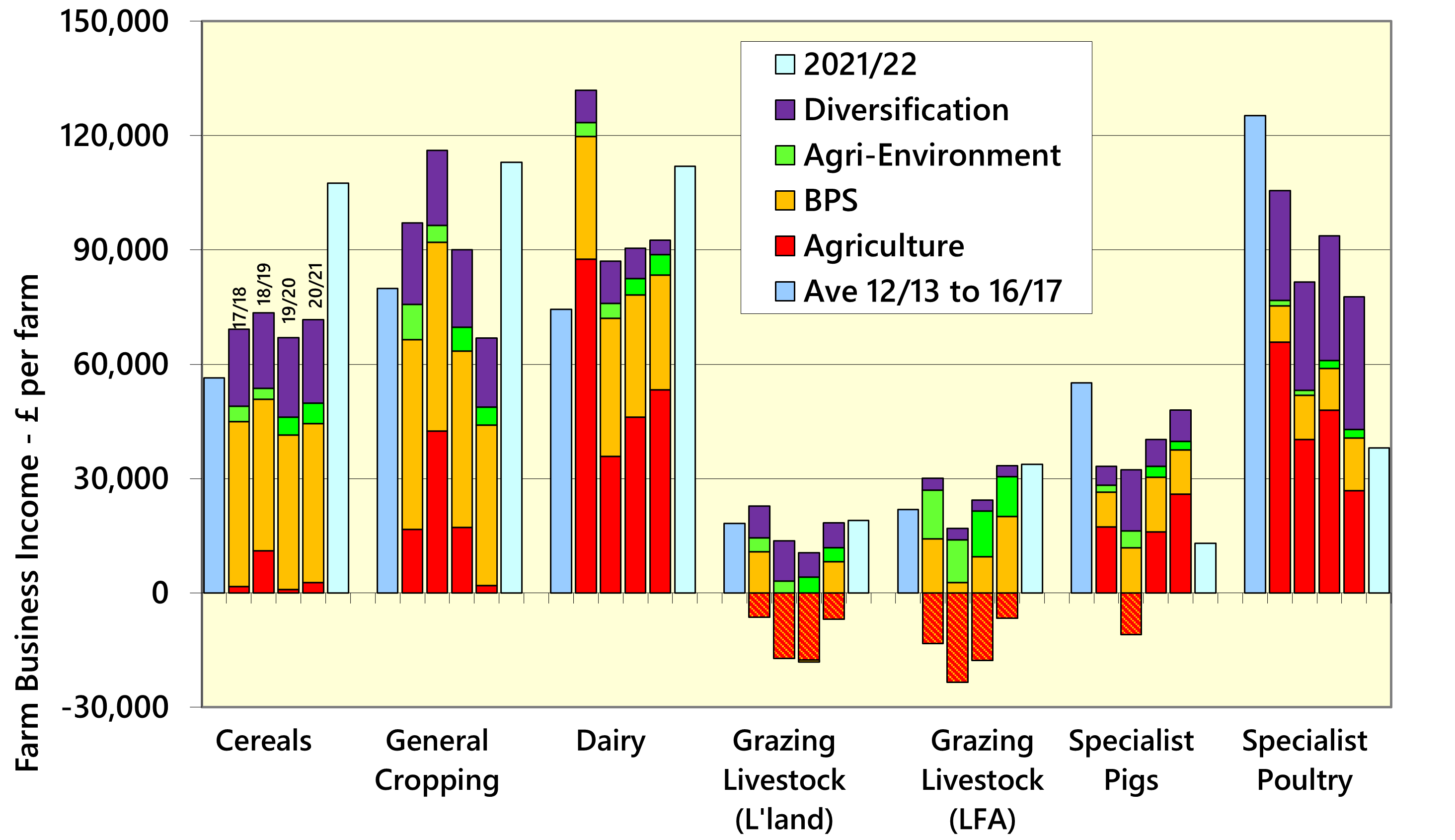

In the chart below, the first column for each sector shows the average FBI from 2012/13 to 2016/17. The next four columns show the FBI for the subsequent four years, broken down into four ‘profit centres’. The final, light blue column is Defra’s forecast for the current 2021/22 year; the data to split down into the profit centres is not yet available. As the chart shows, except for specialist pigs and poultry farms, average FBI is expected to increase for 2021/22. Higher prices for key outputs, such as cereals, meat and milk is expected to result in a rise in output, but this will be offset to some extent by higher costs, particularly for feed and fertiliser. Compared to 2020, the average BPS is expected to decline by about 9% across all farm types, as we enter the first year of progressive reductions.

Source:Defra

General cropping and cereals farms are both forecast to see strong rises compared with 2020/21, 70% and 51% respectively, driven by better yields and higher prices. Even though input costs are forecast to rise by 18% on cereals farms and 12% on general cropping (mainly due to fertiliser costs more than doubling) output is expected to more than offset this.

As the chart shows, dairy farms perform well and have been pretty consistent over the last three years. The current forecast sees further (and larger) improvement, a 21% rise compared with last year. Milk and dairy products are expected to improve by 9% year-on-year, although production is forecast to be lower, strong prices are expected to more than compensate for this.

Grazing livestock farm incomes are forecast to make marginal increases. This is perhaps somewhat surprising given current buoyant livestock prices, but higher crop costs and building depreciation is increasing inputs. As can be seen for the two grazing livestock farm types, the return from agriculture is consistently negative; it takes part (or all) of the Basic Payment to return these farms to profit. This is of real concern when looking ahead to the removal of direct support. This year the Basic Payment is predicted to fall by around 6% on lowland and 9% on LFA grazing livestock farms.

Both specialist pigs and poultry are forecast to see big decreases in their FBI; down 73% and 51% respectively. This is as a result of input costs rising considerably more than output. We have written extensively about how Brexit and Covid has impacted negatively on pig prices, but this has been exacerbated by high feed costs. For pig farms, feed costs, (which typically make up around 50%-60% of all their costs) are expected to rise by about 22% and on poultry farms will be 19% higher.

It’s difficult to know where farm incomes are heading. Cereals and oilseed prices were already high due to tight supplies. Fertiliser is almost now a by product of CO2 production due to sky-high energy prices and red diesel has increased sharply. But this has all now been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. This will now remove large stocks from the 2021 harvest when carryover was expected to be low anyway. May feed wheat prices are circa £300 per tonne and rapeseed £740 per tonne. Both the Ukraine and Russian harvests will more than likely be disrupted for this year and possibly next. Closer to home fuel and fertiliser prices are likely to shape next year’s harvest.