In what is becoming a familiar trend, the Brexit process is becoming increasingly turbulent with civil war in the Conservative party and the stakes being raised in negotiations with Brussels over the prospect of a ‘No Deal’ Brexit.

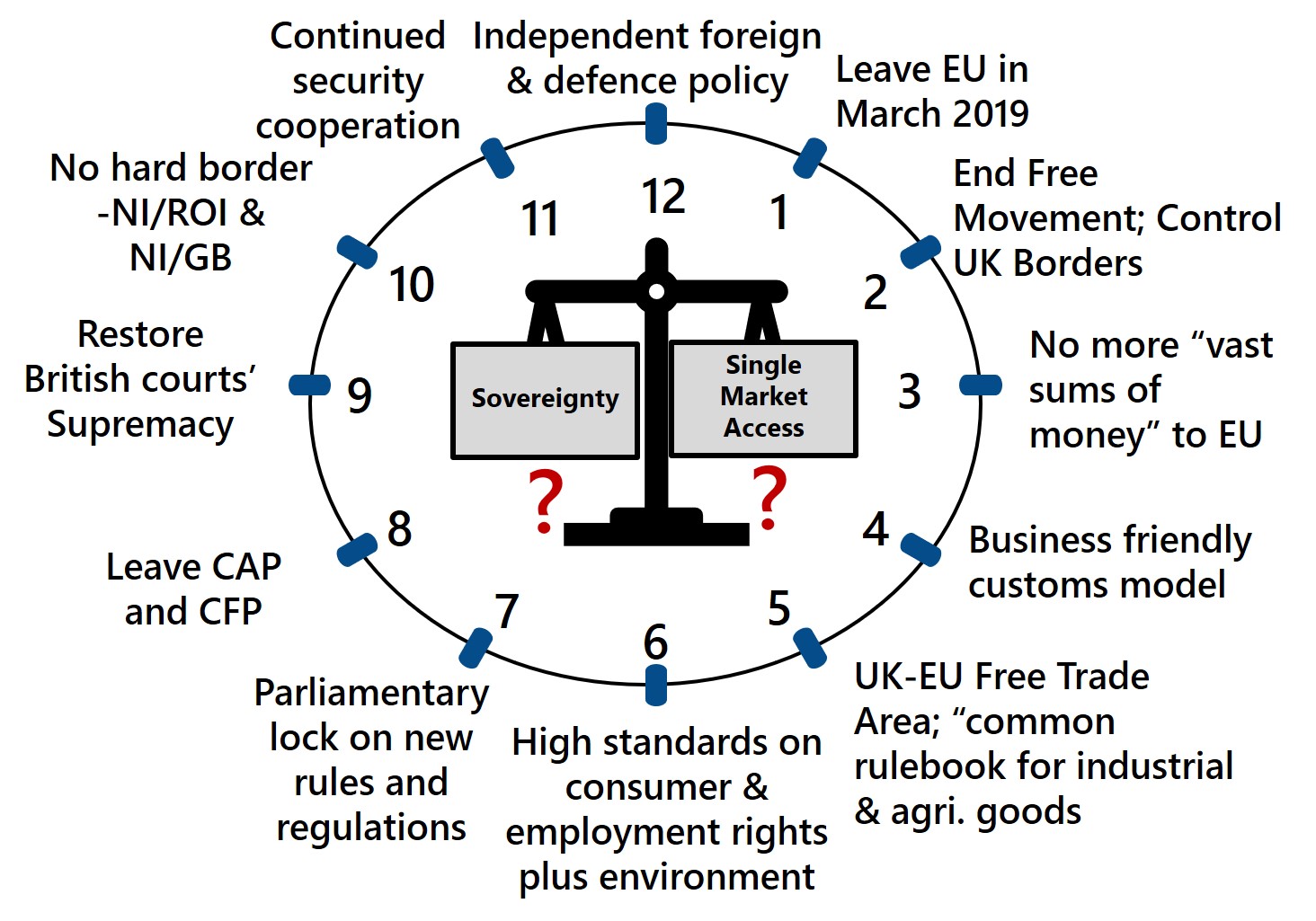

The publication of the Chequers White Paper changed the dynamic with Brussels insofar as there was finally a detailed paper on the table which the EU could negotiate on. However, the sands have shifted in Westminster yet again following last week’s Commons debate on the Customs Bill. Four key amendments were tabled by Conservative Brexiteers which are seen by some as an attempt to undermine the Chequers White Paper:

- Customs Duties’ Collection – bans the UK Government from implementing its plan to collect EU customs duties after Brexit unless the EU agrees to collect tariffs on behalf of the UK. The EU has already made it clear that it would oppose such an arrangement, something which is already conceded by the UK Government in its White Paper.

- New Customs Union with the EU – prevents the UK from entering into a post-Brexit customs union with the EU, without introducing a specific new piece of (primary) legislation.

- VAT regime – requires the UK to operate a separate regime to the EU.

- Northern Ireland – makes it illegal to have a customs border within the UK, thus seeking to rule out a hard border on the Irish Sea between NI and GB. The Prime Minister has already made this commitment, as the UK Government’s opposition to the EU’s proposed backstop is well known. Notably, this amendment did not preclude a regulatory border as Northern Ireland already operates within a separate epidemiological area to the rest of the UK.

Of the four amendments, those relating to customs duties and VAT are the most problematic. On customs, Downing Street is maintaining that the approach is consistent with its White Paper because it envisages that money from tariffs will flow both ways. However, the White Paper has not provided much detail on how this would work aside from a vague reference to using a formula to govern flows of money based on trade patterns between the UK and the EU-27.

The situation regarding VAT is potentially more serious as it withdraws the UK from the EU’s VAT administrative system. This could mean that authorities would have to impose a hard border to check if the proper tax has been applied to goods crossing the border. This will be most problematic on the island of Ireland where there is a 500 kilometre land border. If the UK chose not to impose a hard border, it would be exposed to massive fraud (smuggling) and tax evasion. One possible way to negate this is for the Government to seek agreement from the EU to UK participation in its VAT information sharing arrangements, which would need new parliamentary legislation and would add further complexity, particularly because the EU would likely insist on ECJ oversight.

Although the four amendments complicate an already fraught position for the UK, the reality is that the Chequers White Paper is more of an opening gambit in the negotiations with Brussels. What is crucial for the UK now is to increase the pace of the negotiations with Brussels and to pay attention to the sequencing which it has already agreed. This requires the UK and the EU to firstly agree a Withdrawal Agreement, a legally binding treaty, which will include a backstop on Ireland. This will also be accompanied by a Political Declaration setting out the future direction of the UK-EU relationship. The details underpinning the future relationship would then be negotiated and agreed during the transition period. Undoubtedly, the UK-EU negotiations are going to require further compromises. If the terms of the negotiated deal go against existing domestic UK legislation, then the British Government will simply have to change the legislation. So, in other words, the four amendments and key elements of the Chequers White Paper could be overturned at a later juncture if required.

That said, as the stakes get higher in the negotiations, the chances of a No Deal (whilst still less likely than a negotiated settlement) increase. It is prudent that agri-food businesses start seriously planning for the prospect of No Deal. At the business level, steps to consider include:

- Contingency stocks – there is increasing evidence that businesses are starting to build contingency stocks to smooth over extra delays which could result from border checks being re-imposed.

- Training – boost efforts to train-up staff on customs and official controls issues and procedures which must be followed if the UK is trading with the EU as a third country under WTO trading conditions. Some of this knowledge is likely to be useful anyway once the eventual UK-EU trading relationship is finalised and will be applicable for businesses seeking to expand markets beyond the EU.

- Licensing – ensure that UK businesses have undertaken the steps necessary to ensure that they can continue to export to the EU-27. This could include providing proof of previous trade with EU Member States.

- Mitigating tariffs – most businesses by now should know what the default EU Common External Tariffs are for the products they supply into the EU. What is perhaps less well-known are the Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) options potentially available to mitigate the impact of tariffs. It should be noted that the TRQs available to the UK are limited and British businesses would be competing with other countries for access.

- Managing cash flow – if UK businesses need to start lodging securities (e.g. licensing securities) with EU-27 authorities as well as potentially paying VAT on cross-border consignments, then cash flow will have to be carefully managed, particularly if goods are delayed in transit and payments by customers get delayed.

For policy-makers, actions to consider to help businesses would include:

- Recruiting additional customs and border control staff – the UK Government has already started this process but faces competition from the likes of the Netherlands and Ireland which are increasing their recruiting efforts significantly. In addition to customs staff, the need for veterinary staff is evident. Incentives to encourage veterinarians working in small animal veterinary practices to assist with implementing official controls should be considered, even if they work on a part-time basis. As in parts of the US, programmes to part-subsidise tuition fees for veterinary students if they commit to a period (e.g. 5 years) of working on border controls or associated duties in meat plants should also be examined.

- UK-EU TRQs – given that the close historic trading links between the UK and the EU, a case should be made to the WTO to introduce new UK-EU TRQs that would reflect the historical trading patterns between both parties in the event of a No Deal. Whilst this would not eliminate friction, it would go a long way in addressing tariff-related issues that could arise whilst simultaneously protecting farming livelihoods. Admittedly, there may be some opposition within the WTO on this, but it is worth pursuing given the potentially exceptional circumstances of a No Deal Brexit.

- Official controls and associated checks – given that UK and EU standards would essentially be the same on Day 1 of Brexit, there are grounds for UK exports having a lower frequency of physical checks for products of animal origin (e.g. 1% for sheep meat) than the EU’s default rates (20% for sheep meat). Currently, New Zealand enjoys a 1% physical check rate given its closeness to EU standards, so there is a precedent. This would work in both directions UK-EU and EU-UK as long as standards didn’t diverge and would help to lower the regulatory burden considerably. This arrangement could also include reciprocal recognition of existing UK (and EU) licenses and authorisations so that existing trading patterns could continue and upheaval is lowered as much as possible.

- EU-27 employees – grant all existing EU-27 citizens and residents in the UK something akin to settled status. This will require clear and rapid communication to them, to their employers and their landlords to clarify their rights and obligations. This would at least give businesses some degree of certainty that existing employees could continue to work in the UK whilst giving workers and their families the peace of mind they require to continue to be productive.

It is worth emphasising that the likelihood of a No Deal scenario is still relatively low and that an extension of the Article 50 process (of around 3-4 months) is deemed by experts in Brussels and elsewhere as being more probable if a negotiated deal was not reached in the time available. However, as an industry which has been through many crises in the past, it is always prudent to prepare for the worst case scenario whilst striving for the best outcome possible.