The Government has stepped-up its preparations for a ‘No Deal’ Brexit. On 23rd August it published 25 notices setting out what UK businesses and other stakeholders need to consider in the event of the UK leaving the EU without a comprehensive agreement in place. Over the coming weeks, additional technical notices will be published. In total, over 80 notices are expected. These can be found at; https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/how-to-prepare-if-the-uk-leaves-the-eu-with-no-deal

The documents cover a wide range of topics spanning medical science, research, taxation, and workers’ rights, in addition to farming and international trade. The key points from a food and farming perspective are set out below.

Agri-Food Production (incl. Labelling) and Funding

- Farm Payments – as previously communicated, the levels of cash funding will continue until the end of this Parliament (expected to be 2022) with all EU legislation as it currently stands being transposed into UK law. All rules and processes will remain in place until Defra and the devolved administrations introduce new agricultural policies, either through the Agriculture Bill (due in Autumn) or via devolved legislation. Click here for the Notice on farm payments.

- Rural Development Funding – as outlined previously, Government funding agreed before the end of 2020 will be maintained over the lifetime of any agreement (i.e. after 2022 if applicable). However, after 29th March 2019 under No Deal, Rural Development schemes would be funded directly by the UK Government via existing national and local arrangements. Operationally, there would be no substantive change for farmers, land managers or rural businesses. For more details, click here.

- Producing and Processing Organic Food – from a UK perspective, the same processes would remain in place as currently exist. This includes maintenance of existing standards on labelling and food production, UK organic control bodies certifying British organic produce, recognition of third countries currently equivalent to EU and continued acceptance of EU’s organic products “at the UK’s discretion.” However, as the EU would treat the UK as a third country, there would be changes including;

- logos and packaging – UK organic operators would no longer be permitted to use EU organic logo, but they could continue to use the UK control body’s own organic logo. Defra is investigating the development of a new UK organic logo.

- exporting as organic to the EU – could only be done if business is certified by an organic control body recognised and approved by the EU to operate in the UK. This means UK organic control bodies will need to apply to the EU Commission for recognition. However, they cannot do so until the UK becomes a third country (in March 2019) and the process is estimated to take 9 months. Whilst efforts are underway to speed-up this process, including the introduction of an equivalency agreement with the EU and for the EU to accept applications before March 2019, this would present a major challenge to UK organic exporters. More details available here.

- Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) – no significant implications for UK stakeholders. All current EU legislation would be transposed into UK law. Regulatory decisions on GMO trials would be made as they are now on a devolved basis. Any existing EU decisions authorising marketing of GMO products would be applicable on Brexit Day 1 until current expiry date. Thereafter, any decisions on marketing of GMO products would be made by the UK authorities. For UK exports of GMOs to non-EU countries the rules in EU Regulation 1946/2003 as converted to UK law would continue to apply. See here for more detail.

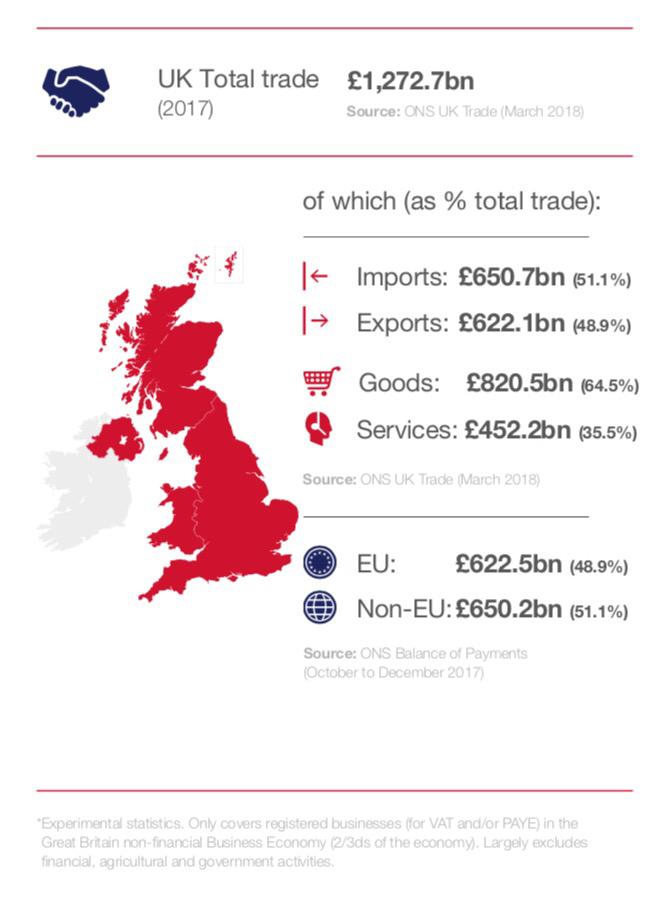

International Trade

- Trade Remedies – these enable WTO members to operate a trading safety net and protect domestic industry (usually via additional import duties) from injury caused by unfair trading practices (e.g. subsidised imports, dumping etc.). As the UK adopts an independent trade policy after Brexit, responsibility for overseeing this area would transfer to the UK Trade Remedies Authority (TRA) which would be operational by March 2019. After Brexit, UK businesses would need to contact the TRA instead of the EU Commission for any complaints relating to trade remedies. In the lead-up to 29 March 2019, any new complaints raised by UK businesses would need to be lodged with the TRA in parallel with the EU Commission, and thereafter, with the TRA only. Further detail on how the TRA would work is available here.

- Trade with EU under No Deal – as one would expect, this is one of the more substantive Technical Notices (accessible here) and outlines the steps businesses should take before and during trade (import/export) with the EU under a No Deal scenario. The UK Government advises that businesses should take the following actions to prepare for a potential No Deal;

- understand what the likely changes to Customs and Excise procedures will be to their businesses (more detail in link above)

- take account of the volume of their trade with the EU and any potential supply chain impacts such as engaging with the other businesses in the supply chain to ensure that the necessary planning is taking place at all levels. The first part of this action should have been undertaken shortly after the Brexit vote. Supply chain planning is trickier and if No Deal occurs in March, there are limitations to what businesses can do at this stage to plan

- consider the impact on their role in supply chains with EU partners. If the UK and the EU do not have a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in place in a ‘no deal’ scenario, trade with the EU will be on non-preferential, WTO terms. This means that Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs and non-preferential rules of origin would apply to consignments between the UK and EU

- if necessary, put steps in place to renegotiate commercial terms (e.g. INCOTERMS) to reflect any changes in Customs and Excise procedures, and any new tariffs that may apply to UK-EU trade

- consider how to submit customs declarations for EU trade in a ‘no deal’ scenario, including whether the services of a customs broker, freight forwarder or logistics provider are needed, or alternatively secure the appropriate software and authorisations

- register for the HMRC’s EU Exit update service via the GOV.UK website

- prepare to register for an UK Economic Operator Registration and Identification (EORI) number, although businesses do not need to do anything now as further information will be available later in the year

- decide the correct classification of goods (i.e. appropriate HMRC commodity code) in advance of any shipments and when making customs declarations (after Brexit) ensure the correct value of goods is entered

- check whether your business needs to apply for import or export licenses for trade with the EU (as a third country)

- for carriers (e.g. hauliers, aircraft operators), ensure that the appropriate Safety & Security declarations can be made for UK-EU shipments

- This notice also mentioned a series of mitigating actions that businesses could consider taking. These include;

- customs warehousing – allows businesses to store goods with duty or import VAT payments suspended. Once goods leave the warehouse, duty must be paid unless the business is re-exporting, or moving goods to another customs procedure. The warehouse must be authorised by HMRC. This may be a worthwhile first step for businesses to take and further information on how to do this available here

- inward processing – allows businesses to import goods from non-EU countries for work or modification in the EU. Once this has been completed, any customs duty and VAT due must be paid, unless goods are re-exported or moved to another customs procedure, or released to free circulation. This could be particularly applicable for cross-border trade on the island of Ireland but will entail additional bureaucracy. (More detail here)

- temporary admission – allows business to temporarily import and or/export goods such as samples, professional equipment or items for auction, exhibition or demonstration into the UK or EU. As long as the goods are not modified or altered while they are within the EU, the business will not have to pay duty or import VAT

- authorised use – allows a reduced or zero rate of customs duty on some goods when used for specific purposes and within a set time period.

- Classifying Goods in the UK Trade Tariff – sets out the obvious point that anyone trading between the UK and the EU will be subject to customs procedures under No Deal, including the potential payment of duties. The detailed information is accessible by this link with key points below.

- for imports into the UK, any tariff rates (i.e. under the UK Trade Tariff) will be based on the UK schedule that it submits to the WTO (a draft schedule is currently with WTO members for review). Based on comments from those who have read this schedule, it appears that the tariff rates are essentially copied and pasted from the existing EU schedule (i.e. the EU’s Common External Tariff). However, the UK will have the right to amend those post-Brexit or could choose to apply a lower tariff as long as it is applied fairly to all WTO members (i.e. under MFN terms)

- for UK exports to the EU, the EU’s Common External Tariff (CET) will apply which as readers will know from previous articles is prohibitively high for some agri-food commodities

- the UK intends to continue offering unilateral preferences to developing countries, and to seek to transition all EU Free Trade Agreements for Brexit Day 1 in order to ensure continuity for both goods imported to the UK, and for UK exports. Further information on this point will be captured in a separate Trade Continuity Technical Notice

- the UK does not immediately plan to change the classification of goods in a No Deal scenario meaning that UK 10-digit commodity codes for imports and 8-digit codes for exports will remain the same, except for a few exceptional standards where codes may need to change to ensure continued alignment with international standards for example

- the Taxation (Cross-Border Trade) Bill provides the legislative powers for HM Treasury to establish a new UK trade tariff.

Taxation and VAT

- VAT for businesses – is one of the most complex areas associated with Brexit. Under a No Deal scenario there would be significant changes for businesses (click here for more details). The UK Government intends to manage this by;

- introducing postponed accounting on import VAT on goods brought into the UK. This means that registered businesses could account for import VAT via their VAT return as opposed to paying upon arrival of goods at the border. Importantly, under WTO MFN principles, these rules would be equally applicable to imports from the EU and non-EU countries. Customs declarations and payment of other duties would still be required as set-out elsewhere. This is a significant measure by the UK Government in a bid to minimise the amount of bureaucracy required under No Deal. However, it also opens-up the possibility of increased “missing trader” fraud where goods enter the UK and circulate freely, while traders go missing and never pay the VAT due. VAT-related fraud is already a major challenge for UK authorities and this proposal potentially exposes the UK further.

- keeping the NOVA system for notification of vehicle imports into the UK.

- employ a technology-based solution for goods valued under £135 to collect VAT from overseas businesses when selling into UK. For goods over £135 VAT will be collected from recipients in similar manner to present arrangements for collecting VAT from non-EU countries

- For exports to EU businesses, as a third country, the UK would no longer need to complete an EC sales list, but would need to retain proof that goods have left the UK. The Government also advises that UK businesses check with individual EU Member States on VAT arrangements as value-added tax would become due at the border upon export into the EU as rules can vary between Member States.

State Aid and Workers’ Rights

- State Aid – the existing provisions of EU law (as transposed into the UK Statute) would continue to apply. However, the Competition and Markets Authority would take over state aid regulation within the UK and would apply to all businesses with operations in the UK (click here for more details). This would mean that from that point;

- UK public authorities will need to notify state aid to any undertaking, through either the block exemption or through a full notification to the Competition and Markets Authority instead of the European Commission

- existing approvals of state aid, including block exemption approvals, will remain valid and will be carried over into UK law under the Withdrawal Act

- any full notifications not yet approved by the Commission should be submitted to the Competition and Markets Authority

- any complaints from businesses about unlawful aid or the misuse of aid should be made to the Competition and Markets Authority. Further guidance will be published by the Competition and Markets Authority in early 2019.

- Workers’ Rights – all existing EU employment legislation will be transposed into UK law. There may be changes to the protections afforded to UK employees working in the EU-27 due to variations in how EU law is applied in each Member State. There could also be changes to European Works Councils if there is no reciprocal agreement between the UK and the EU. See here for more information.

Whilst the above ‘summary’ is quite long, it illustrates that there are going to be major repercussions of leaving the EU without a deal. For readers who have banking, insurance or financial services-related interests in the European Economic Area (EEA) or transact with companies based in the EEA, they should also review this guidance (accessible here). The Horizon 2020 Technical Notice should also be reviewed by organisations receiving funding under this mechanism and there is also separate guidance for organisations receiving funding through other EU-funded programmes (separate to Horizon 2020 and farming-related programmes) which can be accessed here. Further notices (50-60 expected) are anticipated in the coming weeks where problematic areas such as Port Health will be addressed.

If a No Deal comes to pass, there is little doubt that business costs will rise, particularly when trading with the EU and there is the potential for major disruption to supply chains. In the medicines sector for instance, the UK Government is advising six weeks’ of contingency stocks to deal with possible bottlenecks. In agri-food, there is already increased pressure on storage and given the highly perishable nature of some products, the effect of a No Deal would be even more pronounced.

It may appear to some that the No Deal Notices are rather alarmist and that it is perhaps a ploy by the UK Government to steer people towards an arrangement similar to Chequers proposals of last month. That said, the threat of a No Deal is real and needs to be planned for. Three years’ ago, the odds of voting for Brexit were 3:1 (i.e. one in four chance) and it occurred. As mentioned previously, businesses and policy-makers need to prepare for the worst whilst striving for the best deal possible. To that end, The Andersons Centre is hosting a webinar on 19th September which will provide further insights on how to prepare for a No Deal and steps that should be undertaken when making contingency plans. This will include suggested practical actions that businesses should take now and what is required in terms of contingency planning. Further details are available via: http://theandersonscentre.co.uk/webinars/