One of the elements of the Budget which initially flew under the radar was the introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM, from 2027. Perhaps one of the reasons it has gone somewhat unnoticed is that it is an older policy than some of the other announcements.

CBAM was being introduced under the Convservative government, with the policy aligned to the introduction of a similar scheme in the EU. Nevertheless it has garnered attention with talk of charges of up to £50 per tonne for fertiliser once it is introduced.

The scheme is based upon the current UK emissions trading scheme (ETS), and is designed to stop emissions leaks, whereby those industries which are subject to the cap and trade system of the ETS are unable to compete against imports with the same emissions footprint but a lower cost of carbon emissions.

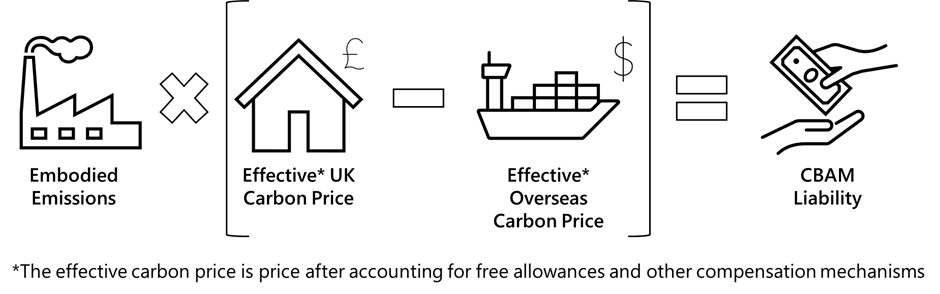

How much extra fertiliser (and other products such as steel and cement) will cost depends on a calculation set out by HM Treasury and detailed below.

From this calculation, it is clear that some of the liability will depend on the carbon price in the economy the product is being imported from. For a significant proportion of UK agricultural inputs subject to the CBAM levy, the EU is the primary import origin. The EU has established its own CBAM, due to start in 2026, it operates through a different system to that proposed for the UK, but would negate some or all of the carbon charge.

There are, however, other nations where there is no carbon costing mechanism in place, or where the cost is comparatively low. A prime example would be for Egyptian Urea. Where this is the case, the cost of urea would go up following the introduction of the CBAM in 2027.

To calculate this liability we need to look at the emissions embodied in Urea. The total emissions embodied, according to the EU CBAM mechanism, are 1.9 tonnes of CO2e per tonne of product. Of this 0.12 tonnes are indirect emissions (electricity) and 1.78 tonnes the direct emissions.

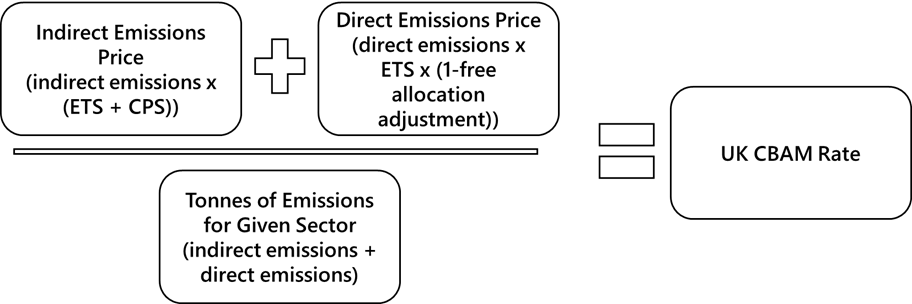

Using a second Treasury calculation we can work out the effective UK carbon price. The calculation for this is set out below.

The current UK carbon price in the ETS is around £35 per tonne of CO2e. This price has been as high as £80 per tonne in the past twelve months. We would expect this value to rise over time. Crucially the carbon price used in the CBAM calculation will be an average of the values of sold carbon in the UK ETS auction. This means that the value of the CBAM rate is liable to be different each month.

The UK also has a Carbon Price Cupport (CPS) in place to support decarbonisation in fossil fuel electricity generation; this is presently set at £18 per tonne. We would expect this to fall as the electricity industry decarbonizes.

Finally, the fertiliser industry benefits from an 80% ‘free allocation’ adjustment. The free allocation is an allowance for UK industry in support domestic production where the UK ETS may result in carbon leakage.

Taking all of these figures into account, then the UK CBAM rate for urea would be calculated as £9.91 per tonne of CO2e. The true CBAM rate will not be known until it is published by UK government prior to the introduction of the CBAM. Due to the complexity of such systems a single CBAM rate will apply to all fertiliser and ammonia imports. However, as one of the more emission-intense products Urea is a useful proxy at this moment in time.

Applying the level of embodied emissions to the UK CBAM rate we can estimate the UK CBAM liability on Urea – the additional cost to the product, due to the CBAM – would be £18.83 per tonne of Urea imported. This is around 5% of the current price of Urea.

Over time we would expect the carbon price to rise, the Office for Budgetary Responsibility currently forecast the carbon price at £44.50 per tonne from 2025 to 2029. We would also expect the value of CPS to decline as will the level of the free allowance. This would increase the UK CBAM liability. The rate of change for these elements is unknown. Using the OBR forecasted carbon cost the UK CBAM liability (with the present CPS and free allowances) would be £23.34 per tonne of Urea.

If all parts of the calculation move as expected, the cost of the CBAM liability would increase over time. However, some of the headline fertiliser price increases being quoted look high to us. We should also remember that a significant proportion of fertiliser is imported from the EU. If there is a reliable reference value for the carbon emissions in the exporting nation, this can be used to offset the UK CBAM rate. Therefore, a lot of imported fertilisers will have little or no CBAM levied on them.

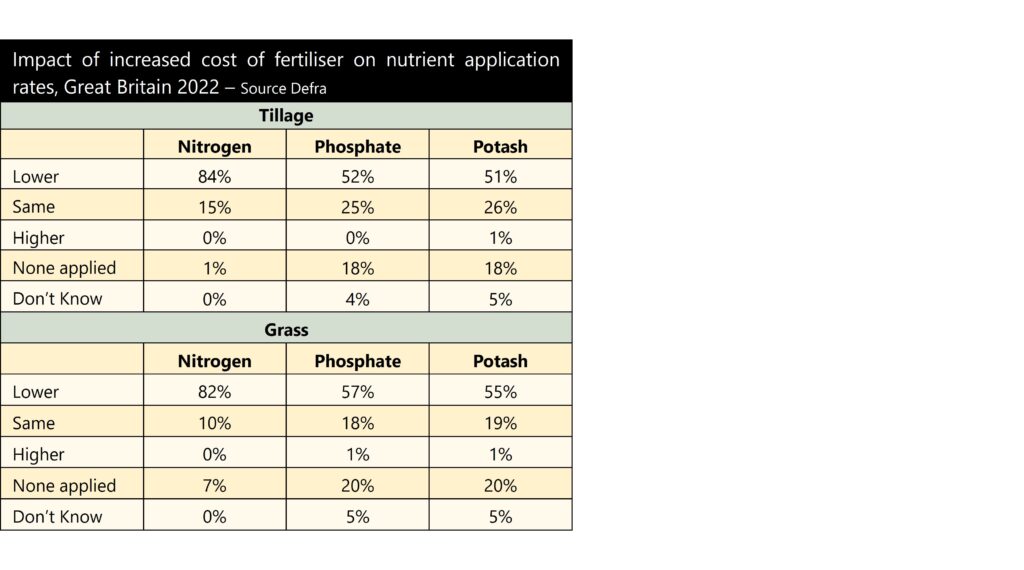

We must also consider behaviour change in this analysis. Over the period of time that carbon prices increase, and so the price of fertiliser increases, we are likely to see a greater focus on nitrogen use efficiency or a shift towards less emission intense fertiliser.