After much debate, the coalition partners of the Irish Government finally agreed on a 25% reduction target for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Irish agriculture (i.e. in the Republic of Ireland) by 2030. The target will have significant implications for Irish agriculture, with the suckler beef sector likely to come under intense pressure.

This target forms part of Ireland’s commitment under its Climate Action Plan to reduce its emissions by 51% by the end of the decade and to reaching its legally binding target of being net-zero by 2050. Previously, the Climate Action Plan, published in November 2021, had mentioned a reduction target range of 22-30% versus 2018 emissions, with a number to be finalised at a later juncture. Farming organisations were seeking a maximum reduction target of 22% whilst environmental organisations were seeking a 30% reduction.

A 2021 KPMG study examined the impact of a 21% and a 30% reduction in GHG emissions on Irish agriculture. It projected that a 6% cut to the beef herd and a 5% cut to the dairy herd would be required if the emissions reduction target was 21%. A 30% GHG reduction would require a 22% cut in the beef herd and an 18% cut to the dairy herd. The agreed 25% target would imply a fall in population numbers somewhere in the middle of these projections, a circa 13-14% decline in the beef herd and a 11-12% decline in the dairy herd. There would also be a hit on the Irish rural economy in the region of €2.5 billion.

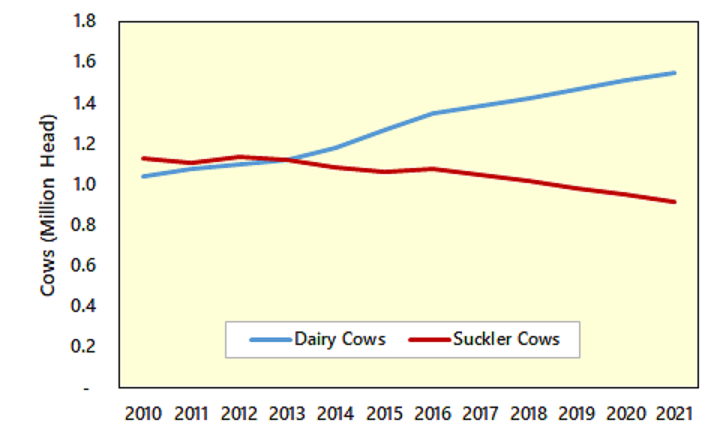

As the chart below shows, suckler cows numbers have already fallen sharply in Ireland, with an estimated 15% decrease between 2010 and 2020. Over the same period, dairy cow numbers rose by 45%. This increase was chiefly due to the shackles of milk quotas being removed in 2015. The proposed target could undo much of the expansion in dairying and poses major questions for the future viability of significant swathes of suckler farming, given its poor profitability.

Ireland Cow Population Estimates 2010 to 2021 (Million Head)

Sources: Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO) and Teagasc

From a UK farming perspective, declines of this magnitude would imply a potentially significant decrease in the importation of beef and dairy products from Ireland. This could present some opportunities for UK farmers. However, British farmers are also likely to be subject to stringent emissions targets as the decade progresses. The Irish Government is at pains to point out that it believes that the 25% reduction across agriculture is attainable without necessitating declines in its suckler beef herd. That remains to be seen.

Overall, these targets illustrate the difficulties that the agricultural industry as a whole will face in reducing its global emissions and going towards net-zero. Of course, the Irish reduction targets above are predicated on the IPCC’s preferred ‘GWP-100’ method of measuring GHG emissions. Some believe that this over-estimates the warming potential of methane and, therefore, penalises agriculture. The alternative ‘GWP*’ method being put forward by some scientists at Oxford University is preferred by the agricultural industry as it treats methane as a short-lived, recyclable, greenhouse gas. Whilst the GWP* method is being re-examined by the IPCC, there is no escaping the fact that all sectors are going to face difficult trade-offs as society tackles the climate change challenge.

The unintended consequences of an individual country striving for net-zero also need close monitoring. If the relatively GHG-efficient Irish beef production is replaced by less GHG-efficient beef from elsewhere, then the planet as a whole will be in a worse-off position. There are similar issues with water; a generally abundant source in Ireland and the West of the British Isles. It is important that produce which is certified as being more environmentally sustainable than the standard achieves a premium price that appropriately rewards the immense efforts that will be involved.

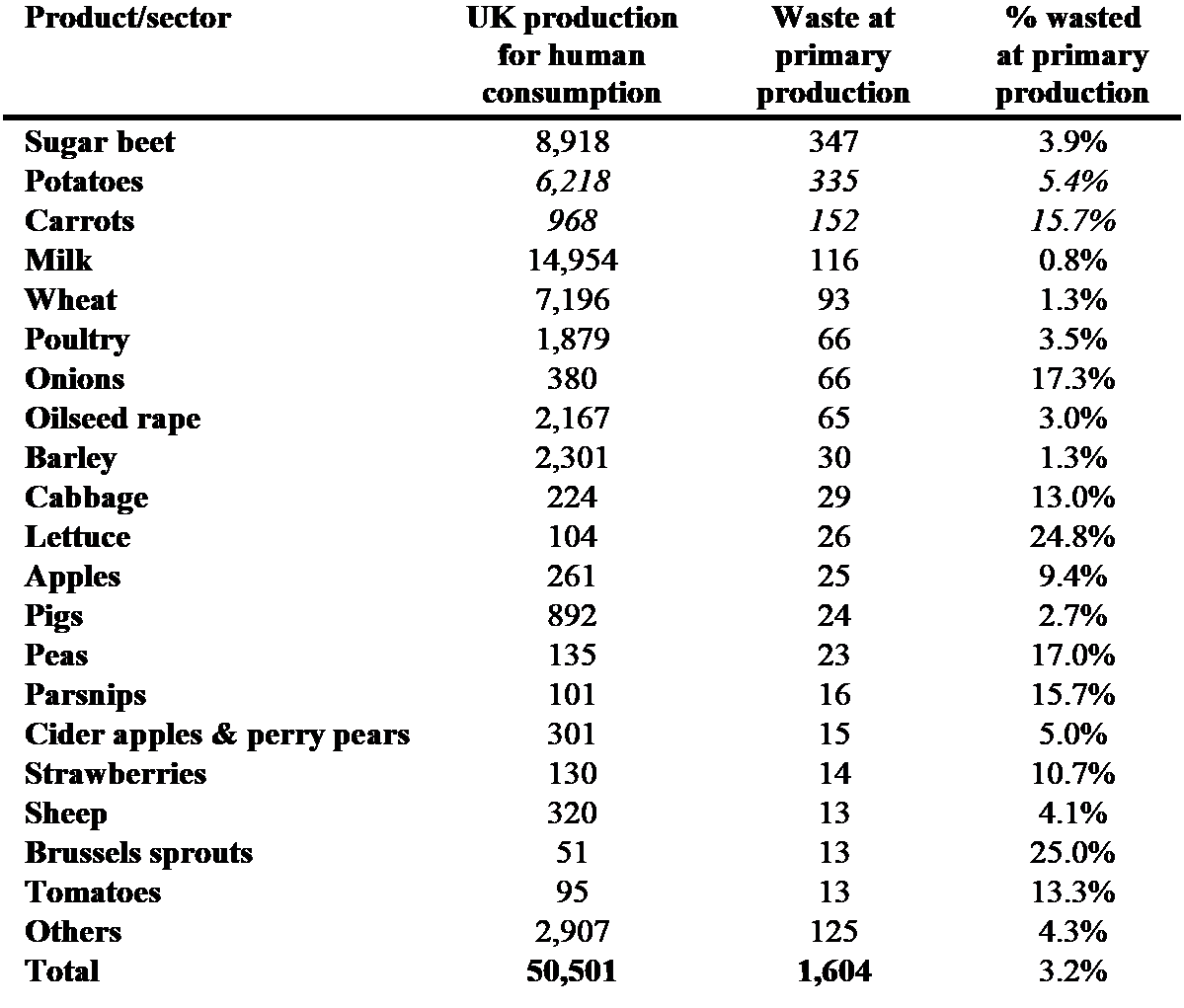

Source: WRAP (2019)

Source: WRAP (2019)