Defra has announced more details on how the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) will operate in 2022 and the years after.

Standards and Rates

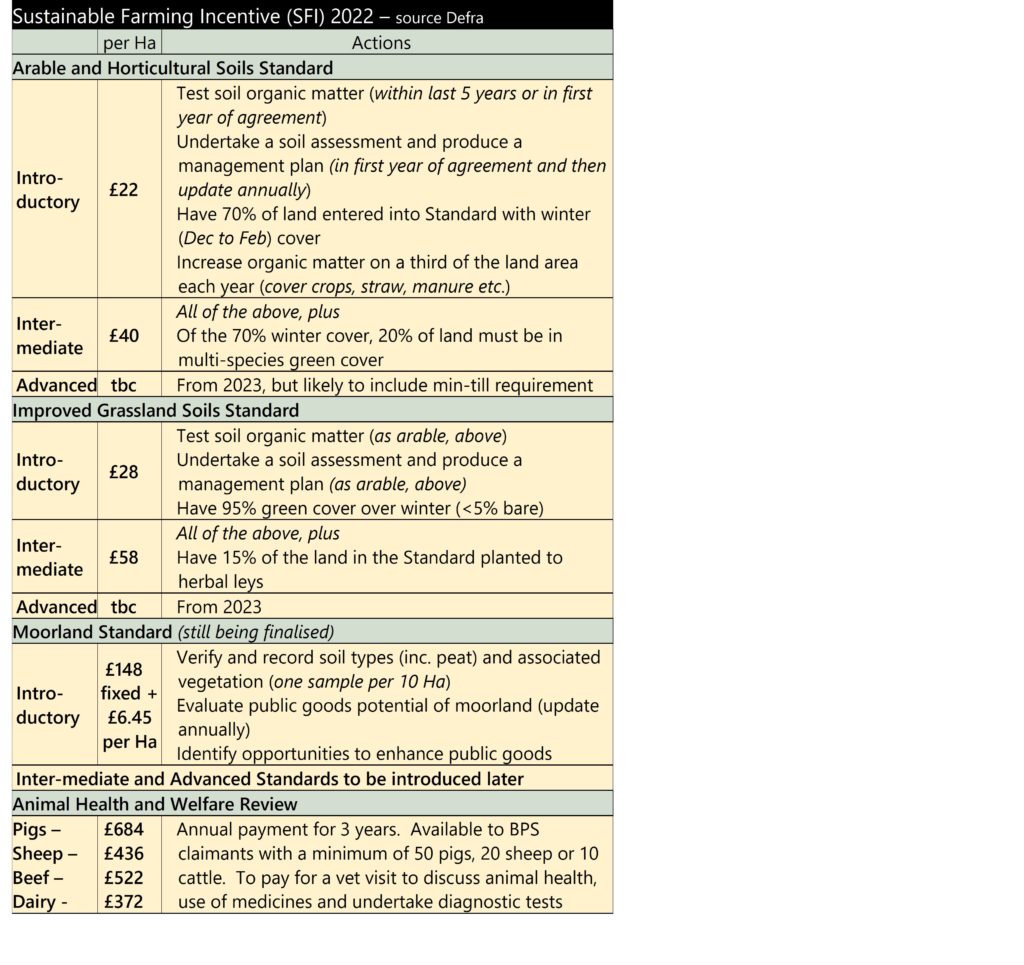

As previously outlined, the SFI 2022 will contain four Standards – Arable & Horticultural Soils, Improved Grassland Soils; Moorland & Rough Grazing and Animal Health and Welfare. The table below summarises the payment rates and actions required;

There will be no capital payments under SFI2022 but these will be added later.

Scheme Rules

The following general SFI rules will apply to all the 2022 Standards and any additional ones added later (see below);

- applicants for the SFI must be current BPS claimants. This restriction will be dropped in future to let other land managers enter.

- SFI agreements will last for 3 years. There will be a 12 monthly review of agreements at which point more land can be added, additional standards incorporated or the ambition level within standards raised. During the 3 year agreement farmers will only be able to reduce ambition levels or coverage in exceptional circumstances – therefore the flexibility in agreements is only one way.

- payment levels will be fixed for the three-year period at the prevailing level when the agreement starts. They may be adjusted subsequently as more experience of the scheme develops. Payment will be quarterly in arrears (i.e. more frequent than current schemes).

- the SFI will operate on a land-parcel basis. Standards can be signed-up for on a field-by-field basis rather than the whole farm having to be entered. It appears that different fields can have different ambition levels under the same Standard.

- land must be under the ‘management control’ of the applicant. This is taken to be the the Tenant under let situations. There will be no requirement for Tenants to gain Landlord’s permission to enter the SFI. Where a tenancy has less than 2 years to run this land will not be allowed in the SFI. As a transitional measure, land with 2-3 years remaining on its lease will be allowed in.

- Land already in Countryside Stewardship (or other existing schemes) can also be entered into into the SFI as long as the prescriptions do not overlap or conflict. This in unlikely for the Soils Standards as they are asking for different actions than CS. It is also stated that land entered into the SFI can be used for biodiversity offsets or other private agreements.

- Common land will be able to enter the SFI through group agreements. A ‘single entity’ (e.g. the Commons Association) will be required to submit the application.

- a 10-week application window for the SFI will open in 2022. The precise timing of this will be given in the New Year (although it is stated it won’t clash with the BPS). Given the statement from Defra that it would like to ‘make the first SFI payments before the end of the year’ this seems to indicate SFI applications after May. In future years, probably from 2024 onwards, applications will be possible year-round

- the monitoring of agreements is stated to be ‘simpler, fairer and more proportionate’ than previous EU schemes.

Future SFI

Whilst only indicative at present, Defra has set out when further Standards may be added to the SFI;

- 2023: Nutrient Management; Integrated Pest Management; Hedgerows.

- 2024: Agroforestry; Low & No Input Grassland; Moorland & Rough Grazing (all levels); Water Body Buffering; Farmland Biodiversity

- 2025: Organic; On-farm Woodland; Orchards & Specialist Horticulture; Heritage; Dry Stone Walls

It is possible other Standards will be included as well. It is notable that in the list above there is no Arable Land Standard or Improved Grassland Standard – both of which were in the Pilot scheme. Possibly they have been subsumed into ‘Farmland Biodiversity’ or they may have been deemed too unattractive.

Other Schemes

The announcement on the SFI was made by George Eustice at a speech to the CLA. At the same time he announced that the payment rates under next year’s Countryside Stewardship (for agreements starting Jan 2023) would be increased. Details of the payment rates are promised in January.

It was also stated that more details on the Local Nature Recovery (LNR) scheme and the Landscape Recovery Scheme would be provided in ‘the New Year’. Landscape Recovery Pilots are likely to be offered in 2022 but Local Nature Recovery Pilots may not be seen until 2023.